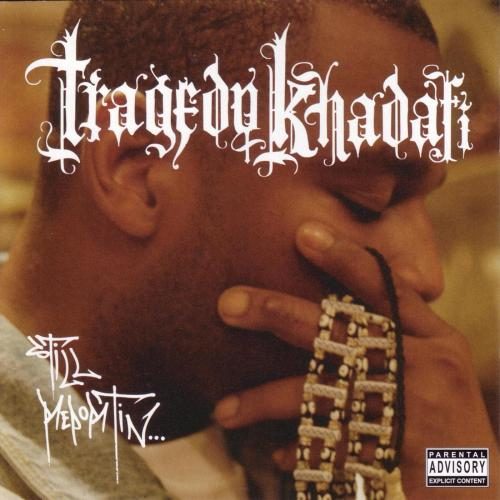

The CD shelves tell us that Tragedy Khadafi has a new album out called “Still Reportin…” Let’s assume we pick it up for one of the many reasons people have for purchasing music. We end up listening to it in the comfort of our homes, vibing to the beats, paying attention to the rhymes. Like it should be. But by now, rap music has become such a common form of entertainment that we rarely ever think about the bigger issues a record like this represents. For instance, can we even begin to understand what it must mean to Tragedy Khadafi that he is ‘still reportin’?

To get an idea, let’s go back to the early 1980s, when Percy Chapman was growing up in New York’s vast building complex known as Queensbridge Houses, with over 3,000 apartments and an estimated 15,000 inhabitants one of the nation’s largest public housing developments. A direct result of the Great Depression, the Queensbridge Houses had been erected in the 1930s to provide affordable and sanitary housing for families who had either no home at all or lived in squalid tenements. Public housing became a federal matter when the Wagner-Steagall Housing Act was introduced under the Roosevelt administration in 1937. Its aim was to get the millions of homeless and unemployed off the street, rid the cities of their dank slums and boost the economy. The first government-sponsored public housing projects were, along with Atlanta’s Techwood Homes, Harlem River (Bronx), Red Hook (Brooklyn) and Queensbridge (Queens) in New York. With doors left off closets, kitchens not being separated from living areas, small rooms, reduced elevator stops and, most importantly, the maximum income for residents set at very low levels, despite dedicated Housing Authorities projects such as Queensbridge were destined to become neglected ghettos of the poor, their population going through demographic changes, but never getting any richer.

Socially and morally, being poor is like living with a weakened immune system, it makes you prone to certain diseases, the most devastating being crime and drug abuse. In some more recent recordings, Tragedy mentions both his father and his mother being addicted to drugs: “See, my mom chose dope, pop chose the pipe / so I rhyme like a triple-beam balancin’ life / hope the scale lean on my side, so I can prevail / most of us lay in a casket or locked in jail,” he described his survival mission in “Permanently Scarred”. But Percy also grew up next to a certain Marlon Williams, to hip-hop enthusiasts better known as Marley Marl, who by the late ’80s would be hip-hop’s first star producer. But it was before he attained stardom that Marley recorded a song with Percy (then going by the name of MC Jade) called “Coke Is It” (by The Kids). While it remains unclear whether this reinterpretation of the famous Coca-Cola slogan refers to cocaine or the even worse crack cocaine that was just starting to spread havoc in inner cities, the message the young rapper was looking to get across was clear. Drugs can destroy entire families, a fact he brutally summed up with the lines: “You could say your mother’s life was a gambling bet / cause she started out with three, she only got one son left.”

Sadly, as an adolescent, the former anti-drug activist fell victim to these dreaded diseases himself, dealing drugs and spending 20 months on Rikers Island for robbery. Because he hadn’t quit rapping, he ended up listening to his contributions to Marley Marl’s album “In Control” while serving time in 1988. It’s a story that sounds all too familiar to fans of rap music, one that seems to repeat itself again and again. When Percy was released by the end of the decade, he didn’t brag about his drug dealing past or his prison term like many of today’s rappers would. Instead, he called himself Intelligent Hoodlum, evoking comparisons to the enlightened but still street-smart Malcolm X after he had embraced the teachings of Elijah Muhammad in jail. Shortly after, a debut album followed on A&M Records, its production in the safe hands of Marley Marl while Tragedy balanced pro-black themes and party rhymes.

Three years later they teamed up again for “Tragedy – Saga of a Hoodlum”. But just as the influence of Marley Marl and peers began to fade, for various reasons politically charged hip-hop lost its grip it had had on hip-hop from the late ’80s to early ’90s. In the wake of Ice-T’s “Cop Killer” drama, record labels began to enforce restrictions on violent content. A&M refused to put out an album by Tragedy called “Black Rage” (which may or may have not been “Saga of a Hoodlum” initially), because of an anti-police song called “Bullet”, eventually dropping him from their roster. You know what happened next. A new generation of rappers brought fame to the Queensbridge. Names like Nas, Mobb Deep, Cormega and Nature became synonymous for the QB and its harsh realities. Rap lost its political edge and became obsessed with the gangsta lifestyle, the music industry again standing by, ready to exploit. And so these young Queensbridge rappers represented the kind of intelligent hoodlum that exerts his brainpower plotting illegal activities. For better or for worse, the public ate their survival stories up.

Where did that leave someone like Tragedy? In 1990, he had declared: “Hoodlum’s the past, Intelligent is the future.” In 1993, he already made a slight adjustment: “Intelligent, but you know the Hoodlum stays behind me.” 1994 and 1995 came around, bringing forth highly influential albums like “Illmatic” and “The Infamous”, and Percy Chapman adapted to the times. He founded 25 to Life Records and released Capone-N-Noreaga’s “The War Report” to critical acclaim. He decided to take another shot at a solo career and reintroduced himself as Tragedy Khadafi on cuts like CNN’s “LA, LA” and Mic Geronimo’s “Usual Suspects”. An album planned for 1998 called “Thug Paradise” never materialized, but with self-distributed releases and/or bootlegs such as the “Iron Sheiks” EP from ’97, “Thug Matrix”, “Thug Matrix II: The Fugitive” and the slightly more official “Against All Odds”, Trag kept his name in rotation.

His current distributor calls “Still Reportin…” the first album he has backed since 1993, and regardless of to what degree this is true, Tragedy Khadafi indeed delivers a well-rounded effort. With production mainly handled by Booth, Scram Jones and Dart La, the album flows smoothly along soulful textures, displaying a broad spectrum of moods with mostly pianos and strings, sounding up-to-date but never clunky or jiggy. From the symphonic strings of Booth’s “The Message (Aura Check)” to Scram Jones’ suspenseful “Neva Die Alone Pt. 2” to Ben And Abe’s riotous “U Make Me” to Just One’s drifting, scratch-driven “The Truth”, this CD is full of well executed tracks, the only real letdown being the too keyboardish “The Code”. The crackling piano sample of the intro will instantly remind you of Mobb Deep (ca. “Hell on Earth”), but while Havoc is an obvious reference for all producers here, they overhaul his beautiful-but-dark formula with a symphonic drive. Just check the street soul Ben And Abe compose for “Can’t Figure”, or “Hood Love”, where Booth not only manipulates soul vocals according to the current trend, but uses different degrees of manipulation to construct an entire track (minus beat/bass) with nothing but vocal samples.

The tracks fit Tragedy like a glove. Like his lyrics they are both emotional and inherently violent. The modern day thuggish Trag reflects the street mentality of young people growing up in places like Queensbridge. “It’s hood,” says his brother Christ Castro who assists him on “Hood”. The fact that “it’s hood” is the starting point for everything else. Love turns into “Hood Love”. And every thought follows the same logical pattern: “It’s logic when dealin’ with the code of the projects / niggas move like unidentified objects.”

With his experience, Tragedy Khadafi should be able to offer interesting angles throughout his writing, but unfortunately his decision to take the thug route forces him to stick to a worn out script. That’s why “Still Reportin…” offers lyrics that place cliché lines virtually side by side with an original choice of words:

“Puttin’ in work, nigga doin’ his dirt

makin’ your life hurt, homie precise with knife work

Got a bisexual nine, a Muslim Mac

Hebrew .45 and a Christian gat

Baptist Uzi and a Catholic shotie

so I gun through your soul, kidnap your body”

Additionally, Tragedy’s lyrics are spliced with Arabic references he must have picked up on some aborted spiritual journey. This goes beyond dubbing Queensbridge Kuwait and likening himself to America’s former public enemy number one, Lybian dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi. The Nation Of Islam is a point of reference (“thugs spread my doctrine like the Final Call”), as well as ancient history as it was portrayed by the various pseudo-Islamic cults that influenced rap music in the late ’80s (Five Percenters, etc.). But because Tragedy’s music today is far from spiritually sound, these references are always served with an unhealthy dose of violence: “Queensbridge the new Egypt / my science is the best secret / I leave niggas paraplegic / it’s fucked up when you need machines to breathe with.” As a reminder of Tragedy’s ‘conscious’ days, “Still Reportin…” also pays tribute to the Black Panthers (“Wake the Dead (Black Aura Skit)”) and struggles to take a stance in a Western world that is increasingly anti-Islam and a rap world that forgot how to be pro-black. “Bin Laden got missiles and I got issues,” he offers in “Walk Wit Me (911)”, stating more precisely: “Me no love Bush, despise Bin Laden / it’s like I’m caught in the middle between two fascists.”

So much for Tragedy Khadafi still reporting. As it is the case for almost all of rap music’s frontline reporters, most of this reporting comes from the perspective of the hood soldier. Here, this results in a couple of chilling episodes (“Neva Die Alone Pt. 2”, “U Make Me”, “Fall Back”). For a little more introspection, check Trag’s dedication to his departed mother (the final “Crying on the Inside”), or his so-called ‘aura check’ “The Message”, the one song that ultimately legitimizes Tragedy’s image change, because it best embodies the few but important drops of medicine he puts into his thug juice:

“Some say that I’m weak, some label me a genius

My mind’s deep, get up in you like a intravenous

Diseases, too many of us thinkin’ with our penis

killin’ the bloodline, the seeds is anemic

Abortions could’ve killed off the next leader

Aura check, step your game up, nigga, the seeds need us”