Although the original 1980s Ghetto Boys consisted of an entirely different lineup, by 1991 J. Prince had assembled the Houston trio we know and love of Scarface, Bushwick Bill, and Willie D for the monumental “We Can’t Be Stopped,” the group’s best-selling album which featured the classic single “Mind Playing Tricks on Me” and an iconic cover photo of the group rushing 3’8″ Bushwick Bill through a hospital hallway after he shot his right eye. Geto Boys became Rap-A-Lot Records’ go-to act on the strength of “We Can’t Be Stopped” and found international fame for their gruesomely violent content, sexual explicitness, militant anti-political rants, and funky southern-fried production.

More than just controversial, Geto Boys proved themselves to be among rap’s most compelling and indeed talented artists, spinning startling narratives with chillingly visual imagery as they took listeners inside the singular realm of their horrific ghetto fantasies. Each member was so individually complex that hearing all three together could be exhausting. There was the pistol-toting, gang-banging midget Bushwick Bill, who portrayed himself as a miniature version of the slashers in the 1980s’ beloved horror films. There was the eternally angry Willie D, a former pugilist who yelled his wild rage into the microphone. And then of course there was the reflective, contemplative Mr. Scarface, the most talented of the three who acted as the glue that bridged Bill and Willie’s massive characters. After “We Can’t Be Stopped,” each member released celebrated solo efforts and watched many artists from their native Houston establish themselves on the national rap radar.

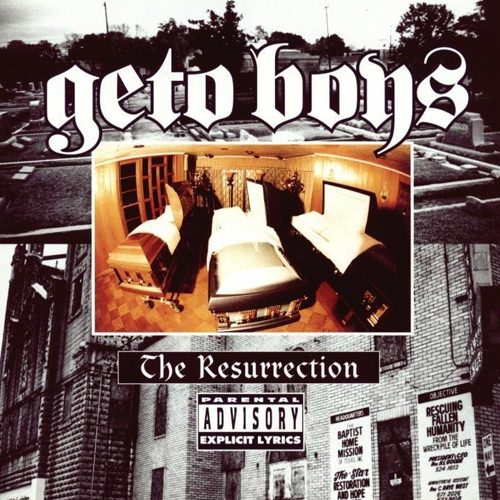

In 1992, however, Willie D cut ties with Geto Boys and Rap-A-Lot, citing financial and creative differences. Eager to capitalize off their still-growing fame, the group soldiered on and replaced him with Houston-by-way-of-New Orleans rapper Big Mike, a Rap-A-Lot veteran, for 1993’s less-acclaimed “Till Death Do Us Part.” Another round of solo albums followed, and finally in 1996 Willie D was back with Scarface and Bushwick Bill for the reunion effort “The Resurrection.”

A whole lot had changed in the five years since the trio had last recorded together. In 1991 the group was labeled dangerous to society and their own distributors slapped stickers on their records warning listeners of its violent content. But by 1996, countless rappers had taken violence and misogyny to a whole new level in hip hop music, and authorities realized that efforts to censor them would provide futile. Also, between 1991 and 1996 Rap-A-Lot had grown from a regional niche label to a coast-to-coast gangsta rap empire, developing a signature sound based on the lean funk of prolific in-house producers N.O. Joe and Mike Dean.

On paper, “The Resurrection” has a whole lot going for it. In the years that immediately preceded it, each member dropped the solo album I consider the best of his respective career (Willie D’s 1994 effort “Play Witcha Mama,” Bushwick Bill’s “Phantom of the Rapra” from 1995, and Scarface’s seminal 1994 classic “The Diary”), and each had expanded his already huge vision both musically and lyrically. And if the Boys were entering their rapping primes, then the same could definitely be said of the producers involved, namely Dean, N.O. Joe, Uncle Eddie, and Scarface himself, who each helped pad the mid-90s Rap-A-Lot catalog with the deep, furious Texas funk that sustained long careers for such modest talents as The Terrorists, Too Much Trouble, Blac Monks, Trinity Garden Cartel, and 5th Ward Boyz. It would seem that 1996 marked the coincidence of Rap-A-Lot’s finest both behind the mic and the boards.

“The Resurrection” is an inspired album with strong political undertones, a smart move positioning the Geto Boys as advanced figures from their days as kings of controversy. In a time when rappers from coast to coast tried to capitalize off the blacklisting of explicit gangsta rap, the Geto Boys instead come armed with a distinct agenda. Interludes feature interview clips of the infamous penitentiary-bound Chicago gang leader Larry Hoover, serving as poignant and thought-provoking bookends about the tracklist.

The opener “Still” is one of the finest tracks the trio ever recorded as a group—for those unfamiliar, it’s the chilling murder rap immortalized in the copy-machine scene from “Office Space.” It’s a perfect opening because it shows that despite five years off, the crew is meaner and tighter than ever, evidenced by their timeless verses-by-committee:

Willie D: “Back up in yo’ ass with the Resurrection

It’s the crew harder than an erection that shows more affection

They wanna ban us on Capitol Hill

Because it’s DIE motherfucker DIE motherfucker STILL!”

Bushwick Bill: “All along it was the ghetto, nothing but the ghetto

Takin’ short steps one foot at a time and keep my head low

And never let go, cause if I let go

Then I’ll be spineless, I’m goin’ INSANE!”

Scarface: “I think my mind just goes outta control

And judge your subjects motherfuckers read about

I touch on the shit that they be leavin’ out

I see this motherfucker’s nine smokin’

I seen the same nigga with the nine die with his eyes open

And simply what this means is

He didn’t know that every dog had his day until he seen his

I bet you motherfuckers will too

Because it’s DIE motherfucker DIE motherfucker STILL foo”

“Still” is a deranged, thrilling masterpiece, and it’s hard to imagine a more effective four minutes of rap. Bouncing off each other with just a few bars at a time, each MC asserts his murderous vengeance between the infamous hook. Equally impressive is N.O. Joe’s track, which would be equally suitable as a horror soundtrack or pump-up jam.

“Still” shows that Geto Boys were still as furious as ever, but its follower “The World Is A Ghetto” is a perfect example of the balance the group gained with maturity. Mike Dean’s thick, twangy production incorporates a soulful hook reminiscent of a gospel tune, and each rapper offers his take on the urban injustice pervading city life circa 1996. For those removed from it, this song might serve as a painful eye-opener, and for those familiar, a long-overdue cry for help. The situation they perceive is one in which the destitute are hopelessly oppressed by poverty and the powerful are apathetic — and as Bushwick Bill notes, it’s not just in Houston:

“Five hundred niggas died in guerilla warfare

In a village in Africa, but didn’t nobody care

They just called up the goddamn gravedigga

And said come get these motherfuckin’ niggas

Just like they do in the Fifth Ward

In the South Park and the Bronx and the Watts

You know they got crooked cops working for the system

Makin’ po’ motherfuckas out of victims

Don’t nobody give a fuck about the po’

It’s double jeopardy if you’re black or Latino

They got motherfuckin’ drugs in the slums

Got us killing one another over crumbs

Think I’m lyin’, well motherfucka I got proof

Name a section in your city where minorities group

And I’ma show you prostitutes, dope, and hard times

And a murder rate that never declines

And little babies sittin’ on the porch smellin’ smelly

Cryin’ cause they ain’t got no food in they bellies

They call my neighborhood a jungle

And me an animal, like they do the people in Rwanda

Fools fleeing their countries to come here black

But see the same bullshit and head right back

They find out what others already know

The world is a ghetto”

Make no mistake — the Geto Boys are still straight outta 5th Ward, but unlike their contemporaries and labelmates, they aren’t glorifying the street life here — in fact, far from it. They paint a vivid picture of the worldwide ghetto as a dark, apocalyptic setting desperately in need of renewal.

The ever-underrated DMG appears on the vicious “Open Minded,” and Mike Dean’s ingenious production shines on “Time Taker,” a reflective downtempo number. Bushwick’s solo track “I Just Wanna Die” sounds like a cut from “Phantom of the Rapra,” a suicidal horrorcore narrative straddling the line between terrifying and humorous, Bill’s trademark. The well-arranged “Niggas & Flies” and the frenetic “Point of No Return” are strong closers.

Although Scarface and Bushwick both turn in career performances, I find Willie D to be most impressive here. Earlier in his career, songs such as “Fuck A War,” “Fuck the K.K.K.,” and “Fuck Rodney King” made him seem like a man who was controversial for controversy’s sake. On “The Resurrection,” his rage seems justified. Take his closing verse on “First Light of the Day”:

“Now you can say what you want ’bout my persona

But don’t let me hear you or I’m go’n freak you out like Madonna

Sneak up on ya, put my gat to your stomach, squeeze the trigga

So close them eyes cause you’s a dead ass nigga

Motherfuckers say I’m wrong because I feel this way

But my environment taught me how to deal this way

And if I kill this way then that’s the way I got to go

Cause everything you reap in life, you got to sow

But I don’t care about the pay down the road from a fool

I’m living for today but if tomorrow comes, cool, nigga

If you think you want to meddle with this

Bring your ass to the square and we can settle this shit

I’m going pop-pop-pop ’til your head start swellin’

Pop- pop-pop till your ass start smellin’

You cried when your grandma died, that was real

But you ain’t got to cry no more, you goin’ to see her

And newcomers get dealt with

‘Cause you can’t get paid if you ain’t part of my clique, nigga

I’m bustin’ anything in the way

Of me seein’ first motherfuckin’ light of the day”

The only shortcomings of the tracklist are “Hold It Down” and “Blind Leading the Blind,” but they aren’t shortcomings in terms of quality, simply in that they aren’t Geto Boys songs and thus don’t quite fit. The former features Scarface’s understudies Facemob on a Face-produced track that sounds identical to those on the group’s forthcoming debut “The Other Side of the Law.” It’s successful in that it garners interest for the group — it nicely captures the group’s eerie sound, and listeners will recognize a young Devin the Dude — it just doesn’t match the feel of “The Resurrection.” The latter song features Willie D and Menace Clan, and although their analysis of dead-end urban leadership is well-conceived and in tune with the record’s theme, Willie makes quick work of the notably inferior Menace Clan.

If “We Can’t Be Stopped” is Geto Boys’ magnum opus, then “The Resurrection” is a close second — a focused, passionate, mature, and musically evolved effort from Houston’s hip hop godfathers. Already considered masters of their art, they showed real growth and renewed vigor. “The Resurrection” is especially compelling because it not only finds three of the South’s premier MCs at their respective bests, but also captures the Rap-A-Lot machine at its musical pinnacle.