Four years ago, when “Magna Carta… Holy Grail” dropped, I considered it mostly a lyrical exercise in an indulgence that was just as pervasive in hip-hop as it was redundant. Though hip-hop music is a youth-oriented institution, if you can spit proper, then age is irrelevant. But my reservations at the time about Jay-Z didn’t concern his age, but rather his unparalleled accomplishments, both personally and professionally. With all that he’s done, what was there left for him to talk about? He’s no longer hungry like he was on “Reasonable Doubt” and “In My Lifetime, Vol. 1“; he doesn’t have a crew anymore like he did on “Vol. 3… Life and Times of S. Carter” and “The Dynasty Roc La Familia“; the man has done it all and rapped about it all. While I liked Magna Carta, I felt that he didn’t have a wide range of topics to discuss going into it. Songs like “Picasso Baby” and “Tom Ford” unnerved me because I felt it was pretentious to rap about owning high-class art. Four years later, I now consider myself to be wrong.

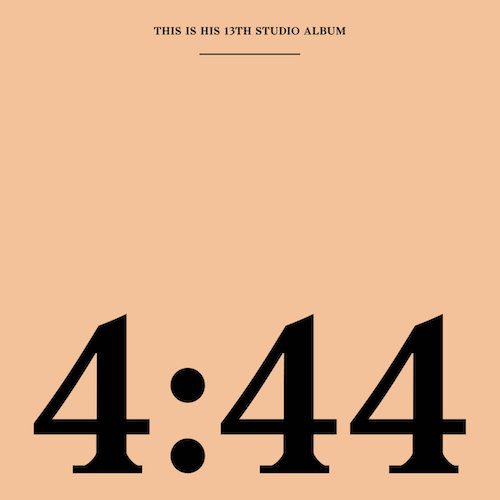

Content-wise, Jay-Z was somewhat pushing the envelope on that album by referencing all this traditional artwork, particularly when you read up on Jean Michel’s history (“Spray everything like SAMO” was a Basquiat reference). His seemingly bourgeois affectations and thirst for “unattainable” things in life was him telling his listeners to wake up and broaden their horizons. While he was bragging, he was definitely not bragging about the same things as everyone else. On his 13th studio album “4:44” that statement rings very true. Actually, he’s not bragging at all. What he does is answer the questions that the public most certain has, and then some. Though he has addressed the dichotomy of Shawn Carter and Jay-Z before, “4:44” is his most personal lyrical analysis of his own juxtaposition of selves yet. A mix of confessions, regrets, life-lessons, and legacies, “4:44” is hip-hop as an adult contemporary style.

Much like his last album, Jay has shown that he can announce that he’ll be releasing an album next week via technological applications and people will devour it in spades. Though this time his album was available exclusively through the Sprint-owned music streaming service TIDAL, the result was still the same. “4:44” has had no lead singles or that much promotion, but he knew the album would sell by the strength of his name and reputation alone. For his business acumen in the streets and the boardroom, he’s an amalgam of Avon Barksdale and Stringer Bell. Veteran Chicago beatsmith No I.D. produced the entirety of this album. It was a good decision for Jay to work with him. The way No I.D. can flip samples makes his music fun to listen to straight all the way through. It’s near-dearth of guest stars here is also a plus. With 10 tracks clocking in at under forty minutes, Jay-Z enlisted just three.

The album’s opener, “Kill Jay-Z”, has been heavily discussed for Hov’s subliminal shots at Kanye West. The concept of the song, however, has Jay rapping at himself, and is a lyrical equivalent of the ending scene of his 2004 music video for “99 Problems” where Jay is riddled by gunshots, reportedly representing the death of Jay-Z and the rebirth of Shawn Carter.

The second track has a beat comprised of a piano sample, accompanying bass, and a sped-up vocal sample. Titled “The Story of O.J.”, he drops some knowledge about what it means to be an Ÿber-successful African-American. With lines like “Y’all think it’s bougie, I think that’s fine, but I’m just tryna give you $1 million worth of game for only $9.99” (which is ironic because TIDAL made this album available for free with no subscription just this past Sunday night), it’s clear he’s been watching House of Cards on Netflix: “He chose money over power. In this town, a mistake nearly everyone makes. Money is the Mc-mansion in Sarasota that starts falling apart after 10 years. Power is the old stone building that stands for centuries. I cannot respect someone who doesn’t see the difference.” He expresses regrets over having so much money at one point with no real financial freedom or the foresight to make smart investments with it. He’s at his most lyrical on “Smile”. With frantic snares and multi-track gospel vocals in the background, he has his mother, Gloria Carter, deliver a Big Rube-like spoken word outro. Also, it’s the most lyrically autobiographical track on the album with a revelation about his mother:

“Mama had four kids, but she’s a lesbian

Had to pretend so long that she’s a thespian

Had to hide in the closet, so she medicate

Society shame and the pain was too much to take

Cried tears of joy when you fell in love

Don’t matter to me if it’s a him or her

I just wanna see you smile through all the hate

Marie Antoinette, baby, let ’em eat cake”

Of course, this review would be remiss if it were not to include at least something about the biggest question about Jay-Z that everyone’s had on their mind. That question was borne of his wife, Beyonce and her 2016 controversial song “Sorry”, which alleged that Jay had a mistress. The title-track on this album finally answers that question and doubles as an answer record to “Sorry”. He confesses his infidelities and apologizes profusely over a soulful sample.

As a man, husband, and father, he expresses a good level of shame at what he’s done. He raps “what good is a menage-a-trois when you’ve got a soulmate”. Apart from his mother, the other two guest appearances on the album are Frank Ocean and Damian Marley on the Nina Simone-sampling “Caught Their Eyes” and the Dancehall style “Bam”, respectively.

One of two standout tracks on the latter half of the album is “Family Feud”. In it, he addresses the current state of hip-hop in relation to the lack of support within rap culture, as well as its perception and inequality of wealth. The second is “Marcy Me”, which is the second best song on the album after “Smile”. The beat has a Marvin Gaye feel to it with the blues piano sample and is a love letter to the Marcy section of Brooklyn where Jay was raised, lyrically applying a mother as a metaphor to represent where he grew up.

Lyrically, Jay-Z still has his gift for wordplay and flow. For what he does not display in terms of technical emceeing ability on this album, he makes up for it by dropping clever gems filled with knowledge. Despite the album’s flaws (the production on “Moonlight” and “Legacy” is their only saving grace), what makes it listenable as far as lyrics go is the that, on one hand, it’s a swipe at his critics. On the other hand, it’s self-aggrandizement mixed with self-criticism. Jay-Z is well-aware of how he’s perceived, but he’s mindful about it now more than ever. With the monumental ambition, drive and success, maybe he should’ve titled the album “How to Make It in America”. After all, nothing succeeds like success.