When people think of values in rap music, they tend to think of valuables. It is common understanding that monetary values are more frequently brought up by rappers than moral ones. But is that so? There exist historically significant denominations in Christianity who put forward that your faith bears upon your success in life. Hence believers have an obligation, within their means, to do well economically as they are seen as God’s custodians. That was but one – more radical – aspect of protestant movements such as Calvinism, Puritanism and Pietism, but the notion that essentially every function is a vocation (and God not only calls clerics but everyone) and that everyone has God-given talents to put to proper use was one of the ideas that drove Christian reformation in the 16th and 17th century. One of influential sociologist Max Weber’s most widely circulating theses was (in its popularized form) that the ethical groundwork for 20th century capitalism was laid by the ministry of reformer John Calvin.

Before you now assume that the richest people are the godliest and all the glamorous rappers you know actually do God’s work, that was of course not the argument of Christians protesting the excesses of the church. In fact followers were expected to be hard-working and money-saving and the community’s wellbeing was put above individual welfare. Pompous and boastful were definitely not attributes that would have granted entrance to the kingdom of God.

But listen closely and you will realize that most mentions of material possessions in rap are meant to attest to an outstanding work ethic (but also cleverness or wickedness). The hustler (i.e. drug dealer), as he appears so often in US rap, is the blue-collar version of the common criminal, sort of like the closest approximation of holding a steady job and making an honest living in an illegal business. In rap rhetoric, wealth is often a sign of virtue, quite simple. It shows you are able to take care of your business. The willingness to work is reflected by the diamond’s shine, so to speak. There are many other values taught in rap music, but this one remains a constant and widespread. Whether you agree with the basic presumption that there’s a deeper meaning behind lyrical and real-life flossing or with the bold conclusion that dealing drugs is not that bad if you sell them by the sweat of your brow, is another question. And crimes are certainly not okay in any religion.

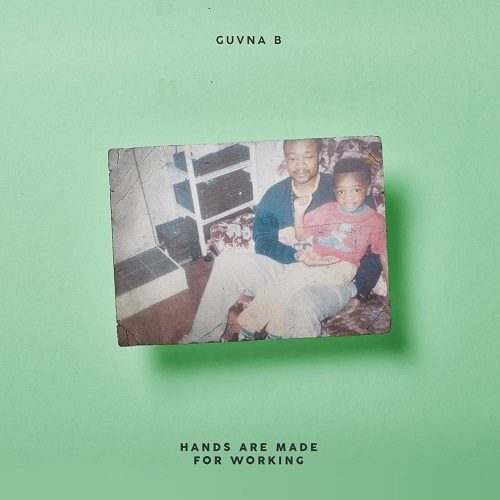

Trouble following? Well, London rapper Guvna B has a more clear conception of the whole issue. His values are unambiguous and he doesn’t have to stretch logic to defend his decisions. He discusses values in the manner of someone who was taught right from wrong. “Hands Are Made For Working” is first and foremost the album of a son who lost his father. The first song recounts the day in 2017 Guvna’s dad unexpectedly died, ending with an episode from childhood that explains the album title. In the songs that follow, the rapper continues to remember pieces of advice his father gave him. Young Isaac Borquaye must not always have been so perceptive. In “Heart of a King” the son of Ghanaian immigrants recalls how he didn’t yet understand when someone told him he would have to work twice as hard. In “Been Hustlin’ (Black Del Boy)” he reminisces on how he turned his life around after thinking “the money would have made me / all it did was change me / had me movin’ crazy”.

Guvna B is a Christian rap artist, that eventually becomes clear. All the more when you learn that his industry accolades registered in gospel categories. But like Lecrae in the US, he possesses an artistic armor that makes him fit to stand his ground in different arenas. “Too grimy for the church / But too churchy for the grime scene”, he describes the potential dilemma here, adding contently, “Still I’ve paved a way”. He masters grime’s brusque rhetoric, exemplified by the slinky and opaque “Everyday”, or vintage grime bangers like “Aight Boom” and “Dun All the Hype”. The Kano influence is obvious in the latter as Guvna confides in a knowing tone: “You know how it goes in the ends / You can be a good guy doin’ good tings but sometimes you know how it goes with friends / Dem man there, you know how it goes with dem”.

A product of the neighborhood, but on his own terms, Guvna B has the authority to tell people when they’re wrong, especially those who are convinced they are not. “Fairytales”, while asking God to forgive their sins, tells killers they ought to serve their full sentence, an argument you don’t often hear that explicitly in rap. He is also man enough to admit that events like his father’s death tested his faith. He has regrets of his own (“Broken”) and reproaches close ones he felt didn’t offer enough support at times. And finally he isn’t blind to the socio-political conditions that weigh on everyday people, teaming up with US artist Jimi Cravity for the dolorous “Interlude: How Long” and pointing to the lack of opportunities for young people in Britain.

Guvna B has overcome these odds and credits his heavenly and his biological father for going from negative to positive (assuming the rest of the family had some influence as well). Next to being an university graduate and ambassador for The Prince’s Trust, he can look back on a decade-plus career in music. Accordingly “Hands Are Made For Working” is an absolutely professional presentation, Birmingham-based producer JimmyJames showing the same versatility as his vocalist. Guvna B is able to connect with the listener with a range of fine-tuned conversational flows that he unleashes over a similarly wide range of musical backdrops. He can rap with no drums, to big drums, he can do ballads (“Cast Your Cares”) and, with the help of Martin Smith, former singer with an established British Christian rock band, pen a more customary tune for a more mainstream crowd (“All I Ever Wanted”). By the time he concludes closer “Summer in the Streets” with a recorded family scene, Guvna B has taken a crucial step towards coming to terms with his father’s death and is doing his best to make dad proud, two objectives also stated within “Hands Are Made For Working” and two objectives so universal they result in an universally valid album.