There has been a lot of talk about the ‘digital divide’ these past years when the number of worldwide internet users steady sky-rocketed. But what does it mean? It means that in the year 2000, there were more internet connections in New York alone than on the whole entire African continent. Think about that, you, the internet user. You are one of nearly 300 million people, part of less than 5% of the planet’s population, but having a 90% chance that you’re reading this from somewhere in an industrialized nation. Face it, you are privileged, no matter where you live.

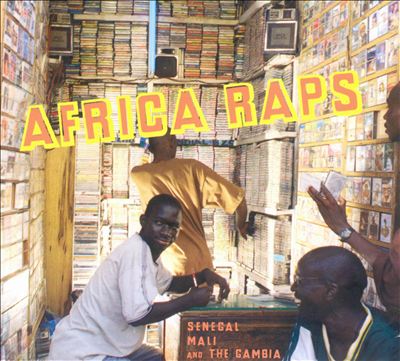

You also have the privilege to show interest in one of the most intriguing contemporary forms of music on this globe: rap music. Rap has gone global, indeed a fact that has been stated many times, but by doing so rap has also, in a way, gone home. Rap may have been born and bred on US soil, but some of rap’s roots reach directly back to Africa. You can link that to different aspects of the rap phenomenon: the dominance of the drum beat, the fact that hip-hop started out in a predominantly black environment, or the tradition of oral storytelling and verbal confrontation. That’s just the shortest possible answer to the question that David Toop touched on with the sub-title of the two sequels to his seminal ‘Rap Attack’ book: ‘African Rap To Global Hip Hop’. I bet you would find some interesting academical papers on this particular subject, but you could also get the word directly from the streets of Dakar, Bamako and Serekunda, as heard on “Africa Raps”, an important collection of 16 tracks gathering hip-hop songs from Senegal, Mali and the Gambia, most of them for the first time issued on CD (tapes are still the music medium of choice for the majority of customers on the African continent). Enclosed you’ll find a bit of information on every song and every artist, also in English.

Since “Africa Raps” concentrates on West Africa, this CD is even more interesting in light of the griot tradition. Griots are the social caste of musicians in that part of Africa, who traditionally served as the living history book of the village as well as fulfilling the role of local newsreporter. American rappers have taken on a similar task very early on. But there’s yet another connection between rappers and griots: I remember reading that Oakland rapper Too $hort, one of the longest living legends of rap music, started out recording tapes for anybody who was willing to pay to hear his or her name mentioned in a rap. The griots had and still have a similar function, in that they are praise singers who work for those who have the money or the power to employ their services. But occasionally they would rate their freedom of speech higher than their payment and use their wit and inside knowledge to mock those they were meant to praise. On a similar note, $hort had this to say: “Playin’ broads ain’t based on love / You want my money? I wanna fuck / and after we do all that / I talk about you in my next rap” (“Something to Ride To”).

Well, that’s maybe too far a stretch, because you won’t hear any Senegalese Too $hort on this collection. For one because this country and its rappers are very religious (predominantly of Muslim, but also of Christian faith), secondly because rap is regularly used as a political weapon. Some of the scoops on these songs are truly incredible. In “Art. 158” CBV denounce the one act in the country’s penal code that’s supposed to fight corruption. The songs is set up much like N.W.A’s controversial “Fuck tha Police”, with some court room drama at the beginning and the end of it. In this fictional set-up they’re facing a sentence based on that same law just because they dared to talk about corruption. Now that’s corruption!

Omzo’s “Kunu Abal Ay Beut” seems to be another hotly discussed track. The song’s title means ‘the hand that gives is the hand that rules’. With the help of a famous film quote, Omzo tries to break (down) the vicious circle that is sustained by short-term humanitarian aid that in the end only supports the ruling class in their aim to keep the people in dependence. Sen Kumpe’s “Lou Deux Bi Lath” comes from the same source as “Kunu Abal Ay Beut”, a trouble-stirring tape called “Politichien” (wordplay with ‘politician’ and ‘dog’). The track calls out a well-known politician who switched sides just for his own personal benefit, incorporating snippets of his own hollow arguments. You ever wished rap would comment on your country’s political system? In Senegal, it seems, that’s a daily routine. Over in the anglophone Gambia it’s the same thing: “Kepp Kui Bangh” by Da Fugitivz talks about politicians who only seem to ‘care’ for people during election time.

While the chance of catching dead prez on “Africa Raps” is much more likely than hearing any Lox, rap isn’t solely a political organ in West Africa. It also talks about social situations. In a rather unexpected collaboration Bibson of Rap’adio and Xuman of Pee Froiss, not exactly known as best buddies, get together to tell the tale of a young man who emigrates to France, only to see his dreams shatter once he gets there and is forced to lead the life of an illegal alien. “Kay Jel Ma” uses a sample of Senegal’s biggest international star, Youssou N’Dour, and is one song that surely a lot of Africans living in France can relate to: “Travelled thousands of kilometers just to get shitty jobs / I’m condemned without a sentence / playing hide-and-seek with the police / my dream has come true, but it’s the worst of my nightmares / I’m longing for my friends and my family in Dakar…” But back in Dakar it’s not all gravy either, as Abass Abass is about to find out in “Urgence”, the Senegalese version of Public Enemy’s “911 Is a Joke”. Another source of public discontent in Senegal is the entanglement of politics and religion and the resulting corruption. BMG 44 are said to have received death threats from disciples of one peculiar religious leader they dared to call out. “Xam” has them rapping in the classic gruff style that has always been a part of rap, rhyming about how everybody knows what’s right, but nobody follows it through. Rather than divide it should unify people, is the stance on religion that Muslim rappers Da Brains take, so they invited a Christian choir to join them for “Axirou Zaman” (‘the end of the world’), not hesitating to denounce religious representatives who make babies they don’t take care of.

But you’ll also hear about specific rap-related problems, such as bootlegging. Not only seems the whole Senegalese music market be monopolized, groups also suffer from piracy. I couldn’t help but think of Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth’s “Straighten it Out” and Brand Nubian’s “Steady Bootleggin'” when I heard “Pirates” by Les Escrocs. You’ll also witness a freestyle cypher (“Libre Ego”) or “Jalgaty” by Senegal’s premier rap act Pee Froiss, which to my ears at least track-wise sounds the closest to US rap. I even think I caught the n-word in there somewhere. Mali’s Tata Pound take a different route musically, not trying to emulate a US sound, but rather incorporating the typically contemporary African pop music in “Badala”, which interestingly enough sings the praise of their neighborhood, so once again rap music comes back full circle. Appropriately closing off the compilation are the founders of the Senegalese rap movement, Positive Black Soul, with their reworking of Baobab’s “Boulmamine”, “Boul Ma Mine”.

I admit it was rather difficult to overcome my own preconceptions about how it should sound when “Africa raps”. In the end, it’s not that different from what I expected. Compared to American, Asian or European hip-hop these tracks +do+ have a distinctly African element to them, there’s no denying that. The quality of both sound and song structure leaves not much to be desired, there’s a wide variety of voices, including singing, there are beats and bass, samples, live instruments, universally used keyboards, traditionally applied guitars, etc. The worst thing would have been if I encountered some wanna-be thugs over wanna-be Timbaland tracks. Thankfully, the West African hip-hop scene seems to have a long enough lasting legacy of its own (just think that there are ‘old school’ vs. ‘new school’ feuds) to truly have an identity of its own. Others might question that and indeed some of the groups here make an effort to go further back in their heritage. Not coincidentally, these groups have met outside of their native country: Djoloff use traditional instruments and wear traditional garments, but the liner notes are quick to point out that they’d get laughed at if they tried this at home in Dakar. While their “Metite” was recorded in France, Gokh-Bi System recorded their album in the US. Even if they’re – not yet – heard in Africa, their message is still noteworthy, as “Xaesal” brands the use of skin bleaching agents.

What surprised me most about this compilation was that these tracks (with a few exceptions) were made strictly for the home market. They didn’t have any world music freaks or the big French market in mind when they wrote and recorded their raps over locally flavored tracks. In fact, Dakar with its over 2000 rap groups seems to be some type of Mecca for West African rap, much like rappers from overseas jet to New York to make use of the knowledge there, or reggae and ragga artists make the trip to Kingston. But even so, this is as local as it can get, and yet, as GLOBAL as hip-hop can get. I think Abass Abass is a hundred percent right when in the opening “Africa Child” he says that “hip-hop and Africa will sympathize” – even though the “tam-tam’s” have been “synthesized”. And I assume that the ever-curious among you will sympathize just the same, despite the fact that you probably won’t understand a word of this mixture of Wolof and French, and neither did I. But sometimes a deeper understanding of hip-hop than just understanding the words is needed, and I think this here CD can help you get a deeper understanding. Because when “Africa raps”, people sure should listen.

In the US, “Africa Raps” is available from Triage International, for a list of all international distributors check out www.trikont.de and for updates on the African hip-hop scene visit www.africanhiphop.com.