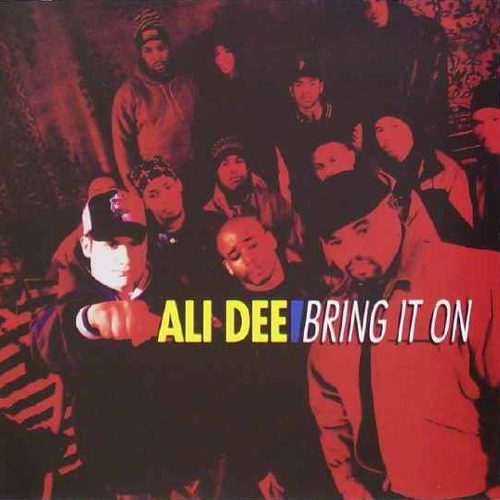

Ali Dee’s career in hip-hop could be a short course in cultural irony. When his “Bring it On” album hit store shelves in 1993, hip-hop heads were quick to dismiss him as the next “Great White Hope.” Artists like 3rd Bass and the Beastie Boys had gone a long way towards solidifying the fact “whitey” had a role to play in hip-hop music and culture, but the unfortunate career of Vanilla Ice had burned down the bridges they built. The great irony is that if Ice had been completely honest about his background and heritage it would have been a non-issue, but instead he was caught in a lie about being “from the streets” and having a hard knock life that he never did. After selling over ten million albums with this phony persona inseperably intertwined with otherwise tolerable rap skills, his music was suddenly as suspect as his image and by extension all other white rappers who “wanted in” to a culture that was not theirs by birthright or heritage. Until Marshall ‘Eminem’ Mathers III came along, the dichotomy of distrust between blacks and whites in rap was as wide as the Atlantic, and even today there still lingers a feeling that white artists are trying to “steal” from their black counterparts in rap. It’s a natural distrust stemming from the days Elvis Presley was dubbed “the white man with a black voice” when his records were played on their airwaves of segregated stations where ACTUAL black artists never got a note on the air. Some musicologists have even proposed that the continual evolution of black soul from blues to rock to rap has been a cultural response to the larger culture adopting such arts, forcing the abandonment of the art to replace it with something the community can truly claim as it’s own.

What does this have to do with Ali Dee, you ask? Just that it was his misfortune to LOOK white, and to SOUND white, at a time in rap where rejecting whiteness was not just the status quo, but a way of life. Ali Dee’s actual heritage stems from the loins of an Egyptian dancer and a Russian Jewish dancer/choreographer – hardly the typical European milquetoast background hip-hop decried as “cave dwellers,” “caucasoids” and “devils” by the most militant MC’s of the 1990’s. Ali Dee suffered by association, even though his credentials were as legit as they come. He had been a breaker since before he was a teen, and came of age as an MC during the same days that Run-D.M.C. and LL Cool J ruled the airwaves. By 1990 he had even taken up producing, and his work caught the air of Hank Shocklee. Again there’s no small irony that the Bomb Squad, Shocklee’s crew, were the producers for Public Enemy – considered (at times unfairly) to be the most militant of all rap groups going. Shocklee took the budding producer under his wing and Ali Dee scored several hits, including Aaron Hall’s “Don’t Be Afraid” from the “Juice” soundtrack. It’s no surprise that emboldened by this success, Ali Dee would decide to produce his own solo hip-hop debut, nor surprising that EMI Records would sign him based on his track record of work to date.

In an ideal world, race would never factor into any consideration of talent. White MC’s would be judged on their merits the same as any other group, just as a highly qualified Asian or Hispanic professional should be more likely to be hired for a job than a less qualified white man or woman. Unfortunately in the 1990’s and even the 21st century it’s not hard to find discrimination of all kinds based on race, gender, religion, orientation, and any other category humans use to segregate themselves from one another. Perhaps the lack of enthusiasm about Ali Dee’s “Bring it On” among rap fans and what’s often dubbed the “Hip-Hop Nation” could be seen not only as a backlash against Vanilla Ice, but as a marker thrown down to “even the score” for all the wrongs that a majority group perpetrates on others. Ali Dee was the minority in hip-hop to anyone who looked at him, his pale skin shining like the eyes of a deer in a trucker’s headlights. And boy, did Ali Dee get runover. He never had a chance. As quickly as this record hit store shelves, Ali’s career hit a dead end. He hasn’t released an album since this 1993 debut and for all this writer knows has never been heard from again in hip-hop.

Far be it from this review to simply say “and that’s a damn shame” without offering you any proof that Ali Dee had something to offer. The album speaks for itself, but it’s likely many if not the large majority of rap fans past and present have never heard a note of it. Those who remember the Pharcyde classic “Ya Mama” though would have no problem with Dee’s duet with Kool G. Rap (yes THAT G. Rap) entitled “Bring it On.” Both sampled from the same source, but Dee’s track had a slower pace that enhanced the depth and resonance of it even more while accentuating it with fat bass and bringing in scratching on the chorus. Both songs are classics, but Ali’s is the classic that you never heard. Peep some of his writtens:

“Breaker breaker, send you to the undertaker

The rapper that’s comin to take ya cause I shake ya like a Laker

Whether knockin boots, shootin hoops, alley-oops

Ali Dee’s hoop funk follow your nose for these here Fruit Loops

You bite like bats, if you heard me rap

Drop somethin fat on a track and take on thirty cats, you dirty rats

So here we go, yell Geronimo

Then pass up a hiney, yo – the flow will make you feel like a tiny hoe

I grand-slam like I’m Van Damme

Act like a lumberjack, in fact the track will slam like a Rams fan

You suck so much you need a nipple

I squeeze a trigger, squeeze a Charmin and I cripple Mr. Whipple

And triple any rapper runnin his flapper tryin to kick it

Pull a pump out on a chump and make him jump like Jiminy Cricket

Flippin it like a page until the damn stage is torn

So bring it on, kid, bring it on!”

Type nice right? It can even hang lyrically G. Rap’s contributions:

“See, I disrespects ’em, or indeed I disrespect her

Your damn Sam Goody’s record makes me laugh like Woody Pecker

The price of hot mics so your spotlights are dimmin

Lyrics are fatter than womens that you see with Richard Simmons

So back up, don’t act up, just be on some good behaviour

You thought it was Lifesavers, the flavor I just gave ya

In fact I pack a disco, my lyrics are slicker than Crisco

Give thrills from Blueberry Hill down to the streets of San Franscico

Like Tabasco I’m hot, if I wanna get ripple go sip on a Cisco

You hookey-playin rookies like they cookies from Nabisco

I shake it, I bake it, I take it to the break of, break of dawn

So bring it on, sucker, bring it on”

There’s definitely more to Ali Dee than met the naked eye. Self-produced rappers are more and more common these days (what better way to up your points on a record deal than by pulling double duty) but back then the work Ali Dee was doing on tracks like his single “Who’s Da Flava” was simply phenomenal. The bouncy swinging funk encapsulates the sound of ’93 in a nutshell, right before the Wu-Tang Clan bumrushed the stage and changed up the whole game. As on the previous track, cuts were provided by the critically acclaimed DJ Clark Kent, although Daddy Rich did the work on the rest of this disc. Dee set out to prove he was no slouch on either side of the board, and in this writer’s opinion he succeeded:

“Grabbin the microphone, give you flavors in pieces

Now tell me can you savor cause the flavor’s like Reese’s

Back up, silly, miggidy-mackin kinda chilly

Stiggidy-step up to my grill and get rolled up like a Phillie

It’s soundin really kind of dope when I kick this

You might know all of my top ten on the list, it’s

the new world order the ruler yes the one who y’all thought fresh

Then I wreck check one-two, who’s the dopest yet?

(DEE’S THE FLAVA!)”

Okay in fairness, he did riff a little bit from Das EFX in this verse, but so did almost every other rapper who came along after “Dead Serious” in 1992. The album is full of well-produced and written songs that cover the entire gamut of East coast sound for the era. “Tap Skinz” could easily have been a Grand Puba song, especially with lines like “I’m so smooth, I got my name on rubber.” The horny horn chorus of “Styles Upon Styles” is straight up Pete Rock, and with that title is it any surprise Phife Dawg was looped for the hook? The relaxed R&B harmony of “Take it Back” is some straight up Heavy D shit, while the uptempo attack of “Got 2 B Real” could be found on a Masta Ase or Naughty By Nature song. These comparisons are not a coincidence – Ali Dee’s album deserves to belong in their pantheon, not only being from the same time period but having beats and rhymes that are just as dope.

By the time things close up on the aptly named “Stompin’ Committee” it’s been an all too short forty minute excursion through the beats and rhymes of a hip-hop mad scientist. Maybe if Ali Dee had come out in 2003 instead of 1993 he would have gotten the acclaim he was due, and still be rapping over his own fat tracks today. Unfortunately in more ways than one, Ali Dee was ahead of his time, and it’s clear neither he nor “Bring it On” got their propers. Whatcha say Flash? Proper. Even Pepsi swilling MC Hammer had more credibility than Vanilla Ice, which unfortunately for Ali Dee was his downfall. Look through the bargain bin at your used CD store, this one’s got the flava.