Few rap artists have ever staged a reappearing act as successful as MetalFace Doom, who, by maintaining an enigmatic and elusive profile ever since surfacing in the mid-nineties, has kept observers in anticipation of his next move. In 2003, he changed outfits at an unprecedented pace, first under the guise of Godzilla adversary Ghidrah, the monster mutant King Geedorah, then as “Vaudeville Villain” Viktor Vaughn and finally as the beat-selecting MetalFingers, serving up another plate in his “Special Herbs” instrumental series. For 2004, he has again several projects in the pipeline. But the first one takes a look back.

Conceived in an era of creative restlessness and major label risk taking, “Mr. Hood” remains one of the most free-spirited hip-hop records of all time. The individuals responsible for this milestone were collectively known as K.M.D., a rather arbitrary abbreviation of the phrase ‘positive Kause in a Much Damaged society’. Members Zev Love X, Subroc and Onyx The Birthstone Kid meshed the youthful innocence of A Tribe Called Quest, the musical patchworking of De La Soul, and the cultural and spiritual concerns of Brand Nubian into a piece of work that was very much their own, a record bursting with energy and shimmering with intensity. But things were about to take a wild turn for the worse.

Onyx had left the group earlier, and while recording the follow-up to their 1991 debut, Zev Love’s brother Subroc was fatally hit by a car in 1993. Zev pulled himself together and finished the sophomore “Black Bastards”. When in early 1994 Elektra aborted its release, allegedly because of Zev’s artwork for the album, a lynched caricature of a picaninny, with typically bulging eyes, unkempt hair, big lips, and wide mouth. These were features fans of K.M.D. were already well familiar with as it had been a variable logo ever since the group debuted, who also appeared on the cover of the one single that Elektra did release in 1994, “What a Niggy Know”. Zev later commented: “It’s not the hanging of a person. It’s an idea being executed – the whole concept and stereotype of our people being displayed as minstrels or servants or fools.” It was a way of using discriminating iconography against itself, a method apparently too complex to understand for a Billboard columnist who took offense after she had seen the cover art, directly addressing “the officers at Elektra and Time Warner” when she wrote: “To promote lynching is just plain evil. (…) Maybe [the brother] needs a refresher course on the entire civil rights movement. (…) Martin Luther King is spinning in his grave.”

The executives in question acted promptly. A week before the annual Time Warner board of trustees meeting, the withdrawal was announced. After the “Cop Killer” backlash, the company obviously felt that further controversy had to be avoided at all cost – the sole remaining K.M.D. member wasn’t even given the chance to change the cover art. “Black Bastards” soon became subject to bootlegging, but didn’t get a proper release until 2000 when Zev released it through Metal Face/Readyrock Records, and it took one more year until a properly mastered edition came out on SubVerse. By then the rapper had already become a key figure in indie hip-hop, now going by the name of MF Doom, whose landmark longplayer “Operation: Doomsday” had garnered him unanimous accolades. The artist with the most singles on Bobbito’s underground juggernaut Fondle ‘Em Records, the ever-busy Doom to this day embodies the spirit of independence that would eventually bring forth a thriving East Coast indie scene towards the late 1990s.

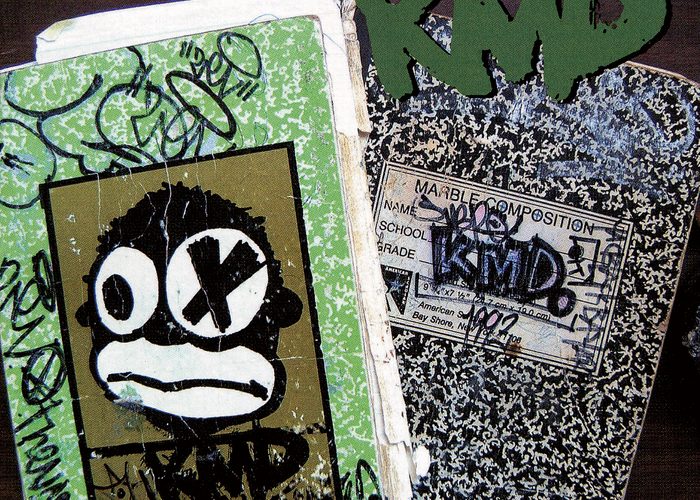

The perpetual popularity of MF Doom has now lead to a collection of K.M.D. material, boldly entitled “The Best of K.M.D.”. By now, just about every nineties hip-hop act that made it past its debut has seen its own greatest hits collection. Too often, these releases were simply a way to squeeze the last cent out of acts whose life-span had expired. Consequently, most of them were carelessly compiled, lacking special treats like liner notes or b-sides and remixes. In most cases, you were better advised to look for the original releases in bargain bins and second hand shops. With “The Best of K.M.D.” it’s a little bit different. “Black Bastards” may finally be widely available, but “Mr. Hood” is hard to come by. On the internet, you might find the occasional overpriced copy, but since there has never been an official reissue in either format, you might want to consider getting to know “Mr. Hood” by way of “The Best of K.M.D.”, even though this reviewer thinks that the somewhat conceptual “Mr. Hood” really shouldn’t be taken apart. While the vinyl edition of “The Best of K.M.D.” doesn’t look like much (generic sleeve with sticker), it’s the CD that might be worth taking a look at. The booklet, while possibly lacking credits and liner notes, features snapshots of the crew’s rhyme book entries. And it wouldn’t be a K.M.D. release without Doom’s Little Black Sambo (literally and figuratively) being exposed on the cover.

But enough of visuals, let’s get down to the nitty-gritty – the music. “The Best of K.M.D.” is divided into a “Mr. Hood” and a “Black Bastards” half, with some bonus track confusion coming up towards the end. Going by the press advance this review is based on, it starts with “Mr. Hood Meets Onyx” and “Subroc’s Mission” (and not the official “Mr. Hood” opening “Mr. Hood at Piocalles Jewelry/Crackpot”). We are introduced to the mysterious Mr. Hood, a character abducted from some obscure language instruction record, dropped into Long Island, New York, ending up tagging along with the crew. “Mr. Hood Meets Onyx” is a great example of how well integrated this sampled voice really is. Only by way of interaction does Mr. Hood turn into this nosy, pedantic person, as his nonsensical sentences straight out the ’50s become subject to Onyx’s joke-cracking.

Mr. Hood makes a few more appearances, putting most other hip-hop skits to shame (“Mr. Hood Gets a Haircut”). What elsewhere would be labelled as filler material, is an integral part of “Mr. Hood”. Don’t be surprised to hear “Sesame Street”‘s Bert assist K.M.D. in banning Sambo stereotypes on “Who Me (With an Answer from Dr. Bert)” and conducting the humming concerto of “Humrush”. And when Zev mentions a “xylophone’s tone” in whatever context, expect to hear a xylophone in the track. This kind of patchworking is typical of hip-hop, but listening to these selections from “Mr. Hood” makes you realize why this particular era is considered a prime period for hip-hop. Elements from the most disparate sources combine to an inspired musical collage, to the point where even the vocals become pieces of the puzzle, “rollin’ in a jazzy-like groove,” as Zev puts it in “Trial N Error”. Yet this doesn’t prevent him from speaking in “bold print like black spraypaint” to get his message across. In other words, these are actual songs discussing real-life matters and events.

There’s the personal account given in “Subroc’s Mission”, a parable about people’s callings they have to obey, whether it’s being a barber, making beats or showing others the way to spiritual enlightenment. There’s the spiritually and socially charged rally entitled “Nitty Gritty”, as K.M.D. (Ansaars) and Brand Nubian (Five Percenters) form the God Squad, delivering five highly original verses. There’s “Peachfuzz”, a charming ‘age ain’t nothing but a number’ plea. And there’s “Who Me (With an Answer from Dr. Bert)”, probably the most outspoken song on “Mr. Hood” that sees Zev Love “X-ercisin’ his right to be hostile.” The track is highly engaging, driven by a catchy guitar loop, its youthful, almost joyous vibe and samples off children’s records almost obscuring the frustration voiced by Zev:

“Holy smokes! I see it’s a joke

to make a mockery of the original folks

Okay, joke’s over, but still it cloaks over

us with no luck from no clover

[…]

Pigment, is this a defect in birth?

or more an example of the richness on Earth?

Lips and eyes dominant traits of our race

does not take up 95 percent of one’s face

But still I see

in the back two or three

ignorant punks pointing at me”

Much more could be said about songs such as “Hard Wit No Hoe”, “808 Man” and “Humrush”, but the truth of the matter is that each one of these would take up time for a description that could never be aedequate, especially since they represent the even more playful and even more intricate side of K.M.D. And then there’s still the second half of this album, introducing the ill-fated “Black Bastards”.

From the onset, it is evident that K.M.D.’s sophomore effort treaded darker waters than its predecessor. The intro, “Garbage Day #3”, quotes movies instead of children’s records, and as people curse and gunshots sound off the harder edge is almost tangible. In fact, the profanity heard during this second half can come as a shock after you’ve sat through the crispy-clean first half. Nevertheless, Zev and Subroc once again serve up some highly entertaining tunes. Hard drums and a dope high-octane organ underpin their word associations on “What a Niggy Know”. “Sounded Like a Roc” may be notorious for Subroc’s eerie “If I be ghost, then expect me back to haunt” line, but it’s also a very solid cut, highlighting K.M.D.’s penchant for melodical basslines and Subroc’s phonetical flow that sometimes borders on jazz scatting. The title track is a “Who Me Part 2” of sorts, but this time Zev points the finger at those who succumb to the stereotypes (“You suck your teeth, I get you back”), concluding: “Black bastards and bitches, which reminds me, I left them out / Two for my list of shit I don’t give a fuck about.”

“Black Bastards” not only featured all the bad words that get you a Parental Advisory sticker, it also contained a considerable percentage of alcohol. Zev’s “pass that 40, man, I’m tempted to swig” in “What a Niggy Know” was a first attempt for the bottle, before the binge began with “Sweet Premium Wine”, a toast to a kind of wine that this reviewer suspects is anything but ‘premium’. The rambunctious beat evokes comparisons to the Young Black Teenagers hit “Tap the Bottle”, but you can’t help but notice the undertones when Subroc offers:

“I be livin’ in a bottle, I be in it

to win it, or maybe even steal it

Don’t let me top-to-bottom

It better be cold, let me feel it

I got stress, I sip booze to heal it

Take your time, relax your mind

I relax fine with premium wine”

“Contact Blitt” is, apart from Zev’s excuse to use all the curse words he held back during the debut, a bugged out account of life on the road (when K.M.D. were touring with labelmates Brand Nubian and Leaders of the New School), while “Smokin’ that Shit” featuring Kurious Jorge, Earthquake and Lord Sear comes across as an impromptu cipher despite the theme that ties it together. All this results in a angrier, louder, bolder second half of “The Best of K.M.D.” The playfulness is still there, but it’s evident that by 1993, bad influences had invaded K.M.D.’s playground. In some ways, the two K.M.D. albums can be compared to “3 Feet High and Rising” and “De La Soul Is Dead”, with the ceveat that K.M.D. somewhat let their anger cloud their artistic and intellectual expression. They were able to shake the “Peachfuzz” image Elektra was previously looking to exploit, but they also dropped most of their spiritual baggage. It’s almost tragic to realize that Onyx once declined when Mr. Hood asked for wine or beer (“Mr. Hood Meets Onyx”). So in regards to Zev Love X/MF Doom, “The Best of K.M.D.” lets on that this would have been a troubled phase either way, with or without the passing of his brother and the losing of his contract.

But before you dismiss “Black Bastards” as a disillusioned debauchery that was rightfully shelved, check the soulful strut of the omitted “Popcorn”, which indicates that at least musically, Zev Love and Subroc were very much at ease. “The Best of K.M.D.” closes with the “Dog Spelled Backwards Mix” off the “Nitty Gritty” single. Busta Rhymes replaces Grand Puba, K.M.D. slightly alter their lyrics and remix the track in a more club-friendly direction, belieing whoever claims they ‘invented the remix’. Inexplicably missing from this compilation are the “What a Niggy Know” remix with MF Grimm, the first b-side “Gasface Refill”, and the integral of “Plumskinzz”. But even so, this is well worth checking for fans of hip-hop’s most beloved luchador as well as anybody interested in more obscure early nineties hip-hop.