“Now in my natural habitat, I gravitate towards the real

And I elevate, on havin that, and I’ll never get caught by the frills

From Yellowstone to Venezuela, Nigeria to the hills

Somethin I learned that I gots to tell ya, it’s niggaz like me got skills

Now I coulda been your doctor or your lawyer, or come to your house and build

But self destruction WILL destroy ya, if you don’t know how to use that shield

See men are murdered, and women raped, and to get it on tape is a thrill…

… And people elsewhere tryin to escape, just to come.. to the show and chill”

Hip-Hop is often by nature a close-minded and insular culture. It’s rather perplexing when you consider that the arts, from b-boying to turntablism to rocking the mic to tagging up walls are all vital forms of self-expression that arose out of a condition where people had not been given a voice to speak their minds. Whenever a group pushes a new form of self-expression outward from it’s core constituency, the natural tendency of people is to adopt and adapt that form of self-expression as their own. Some will do it just because it’s trendy and new. Some will do it to adopt a hipster aesthetic and be “cooler than thou.” Some few will even adopt that form of self-expression simply because it’s far superior to any that have come before; recognizing that prior modes are outdated and unable to convey self. Whatever their reason, the core culture views these newcomers with suspicion and distrust. The core culture sees adoption of these forms by outsiders as tantamount to the destruction of the very art itself, because even with the noblest of intentions the outsider will without realizing it water down and dilute the vibrancy of the new arts generation by generation until it is so widely assimilated by the masses it no longer has any impact. The core group therefore attempts to “own” these forms as a copyright holder would intellecutal property and works hard to bar entrance at the gate to outsiders.

Ultimately such efforts are futile. Proponents of copyright freedom like to say “information was meant to be shared,” which is why the natural order of man abhors a restriction on who owns that information and how they can limit it’s use. Society often invents it’s own ways to circumvent copyright law when the law fails to keep up with advances in technlogy that further sharing information. So too is the way of self-expression, no matter what culture gave birth to it or how they intended it to be used. In an increasingly smaller world with ever more ways to transmit messages and share ideas, new arts eventually leave the hands of their creators regardless of how insular the culture may have been. There has been a tendency over the years by the creators of new black music to view such widespread adoption of the arts as a failure; some would even say a tendency to write off the art no matter how vibrant as passé and immediately go on a search for “the next big thing.” As spirituals beget blues, as blues beget jazz, as jazz beget rock’n’roll, one form turned to another in both evolution and revolution – the natural progresson of self-expression accelerated by distrust and distaste for outsiders doing “our thing.” In all fairness this distrust is warranted when one looks at historical examples of black musicians being barred from the rewards of commerce in their art while white artists from Elvis Presley to Kenny G raked in millions of dollars doing poor imitations of the originals (without even crediting the originators).

Thus results the uncomfortable dichotomy of Hip-Hop where millions of onlookers from the outside in see it as being new, hip, or better than what came before while the core constituency tries their best to circle the wagons to protect that culture. The very act of marketing that culture is self-defeating though, since Kurtis Blow couldn’t control who bought his self-titled debut nor could Sugarhill Gang walk into a store and say “sorry whitey not for you” and take “Rappers Delight” out of a kid’s hands. Hip-Hop has always sought to counteract this cultural dissemination of the new arts through “keeping it real,” a philosophy that no matter how far and wide the arts spread that only those who grew up in the dire economic disenfranchisement that gave birth to the arts could authenticate whether a performance of the art was real or not. Therefore even if Vanilla Ice sells 11 million copies of “To the Extreme” his ability to dilute the culture is stopgapped because by not being from the ghetto he is “not real” and therefore not making real Hip-Hop. This results in a comedy of the absurd where both the cultural core and the onlookers from the outside engage in a one-upsmanship battle of being “more real,” as seen by Ice’s absurd attempts to proclaim himself “from the streets” when his background was in fact purely suburban, or as seen by N.W.A proclaiming themselves “Straight Outta Compton” only to find dozens of new rap artists who were or weren’t from the same hood claiming Compton as a way to be “more real” to their intended audience.

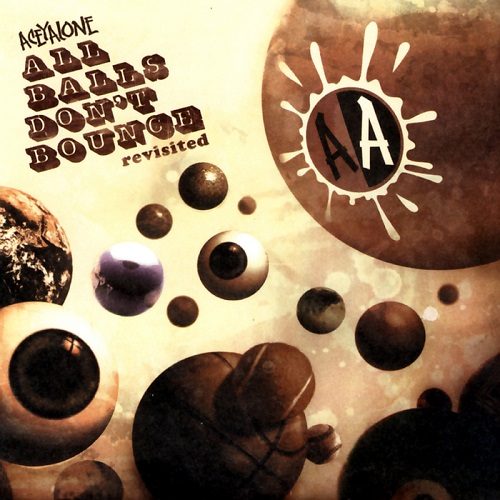

While it’s easy to spot a white man wearing black face, and relatively easy to spot a “studio gangster” claiming to to be hard when he’s not, it’s truly frustrating to the “keep it real” purists to deal with an artist like Aceyalone. On the one hand he’s as culturally core as can be, having the look and sound of that hallowed inner sanctum of “real” hip-hop. Aceyalone refuses to play by the conventional rules and limitations of the culture though. He’s not in the least bit interested in “keeping it real” unless real happens to mean “really innovative.” He’ll rhyme with or without a topic, with or without a beat, and with or without an intended audience for his work. Acey’s style and his music represent the purest form of lyrical self-expression in hip-hop, which ironically poses the greatest danger to the core constituency who want to keep hip-hop from being diluted. Try as they may though Acey’s music can not be limited, nor can his target audience be controlled, nor can his impact on the culture be denied. Even though he has not been a huge sales phenom throughout the course of his career, his very willingness to defy convention in art and style can be said to have had a ripple effect outward from his Los Angeles roots that over time increased in magnitude to cultural quakes that would register on the Richter scale. Artists of all different backgrounds and persuasions can thank him for breaking down walls with the 1995 release of “All Balls Don’t Bounce”; everyone from Cannibal Ox to the Mountain Brothers to K-Otix and even more mainstream artists like Jay-Z and Snoop Dogg are in ways both small and large influenced by this landmark album.

The culture’s response has ranged from both passive indifference to outright hatred. To the “keep it real” crowd Aceyalone’s music is “nerd rap” meant for backpackers and crackers who are so far outside the core cultural constituency that they are not even relevant to the genre and art at all. The tight grip they squeeze around Hip-Hop in dismissing Aceyalone only makes the art and culture slip through their fingers even faster. To the inevitable end, Aceyalone shrugs his shoulders and says “if you relate to it that’s cool.” In 2004 it’s already too late to put the lid back on Pandora’s Box, as 25 years of marketing and selling rap music and the larger hip-hop culture that surrounds it have disseminated it to every part of the globe. From the plains of Nebraska to the mountains of Japan, from the barren tundra of Alaska to the hot sands of Egypt, hip-hop is everywhere and everybody is doing hip-hop. The truest irony is that Aceyalone is not the cultural destroyer his critics would envision him to be, but rather the vanguard of hip-hop’s vitality. Self-expression is after all at the heart of hip-hop, whether a black man raps about travelling through outer space at magnificent speeds or a white man raps about growing up poor in Eastern Michigan. Hip-Hop doesn’t become removed from the cultural tree that gave birth to it, it plants seeds in other areas and gives birth to even newer and grander branches of the arts. As Kurtis Blow begets LL Cool J, as LL Cool J begets GangStarr, and as GangStarr begets Aceyalone, hip-hop evolves and in doing so retains it’s vitality even as it spreads far beyond it’s New York roots.

A re-examination of Aceyalone via the re-release of “All Balls Don’t Bounce” shows that hip-hop is doing just fine. Acey himself is the diaspora of his genre, encompassing every stereotype and surpassing all of them. His very words at the start of the title track indicate what he thinks of other people calling his raps nerdy or his words fake: “Now how the god damn pot gon’ call the kettle black? That’s bullshit!” Over a bouncing bassline from The Nonce with seemingly chaotic horns and instruments inserted at will, the limitless Aceyalone flows effortlessly and freely without any worry about how it will be perceived or received. He does what he does, you either buy it or you don’t, but that’s no good reason for him to not be as creative as fucking possible:

“You ended up a swiggler, caught in a swiggle

Just gimme the signal and I’ll state the terms

As long as I can be there when faith returns

You smokin on sherm or whatever the name

You’re a trivial part, in a trivia game

Now what’s yo’ aim? A presidential campaign

like Ross Perot, he lost it though!

But he got a billion in the bank for show

Oh me I’m po’ – and you like me

But I don’t like you, nigga you all fronts

And I won’t let one apple spoil the bunch

Now get yo’ hat, & get yo’ coat

All afloat, we goin back to the real

I got a question, answer me this

What if me and you got caught in a twist?

And you accidentally got caught by the fist

What’s the gist, or what’s the justice?

Or better yet what if I had got busted

for tryin to go out like General Custer?”

At times his rap seems to be pure stream-of-conciousness, and at other times it seems to be poignantly sharp, as he throws barbs at the “keep it real” crowd who are actually faking a front and not really being real at all. If reality is being yourself, then Aceyalone is the king of keeping it real. The fifteen tracks of this re-release run the gamut of sounds and styles. “Anywhere You Go” is Acey at his braggadocious best, putting himself over inferior competitors lyrically while simultaneously his melodic flow and refusal to follow A-B rhyme structure make the point for him. “Deep and Wide” has a deeply nuanced spiritual flow, the extra-terrestrial “Mr. Outsider” confirms his intention to stay original, and “Annalillia?” is an ode to the fly girl he wants to roll with. What’s scary and impressive is that this broad range of sound and style is only the first five tracks. Acey goes from an old school sound on the shot-calling “Knownots” to a positively mindbending tempo and flow style on “Arhythamaticulas” to a resoundingly hardcore attack on “Mic Check” where Acey proves he can even be as vain as rap’s biggest flossers and ballers – or maybe he’s just straight up mocking them:

“if it wasn’t for a mic check you wouldn’t have a check at all

– a one two, and I’m a check you

[…]

I’ll be movin fast on that ass, I stipulate your fate

I take a grip I’ll take a shot I’ll break your plates

Now can you take the weight or do I have to make it lighter tighter

than you could imagine that I had to been when I recite a rhyme

I might as well be inside of your mind

I know you thinkin, “Damn! How does he? What was he a man

or a machine with computerized diagrams?”

I tell em, “Nope! I am of the flesh, fresh, dope”

I’m set apart you’re just a shot in the dark

and the darkness casts no shadow

And I’ll be victorious, no matter who I battle

So every rapper in the house shut the fuck up!”

The production is as diverse as Acey’s rap, with everyone from Punish to Vic Hop to Mumbles and Fat Jack handling the duties. While the styles range from the slow snapping poetry slam jazz of “Makeba” to the upliftingly fluid harmonies of “Keep it True” featuring Abstract Rude & Change of Rhythm, each beat feels perfectly chosen for the impact of Acey’s verbals to be amplified beyond the limits that had previously been conceived for hip-hop. And on a personal note, this reviewer would like to add that Aceyalone’s opening words on the latter track ring especially true in a world overflowing with narrow-minded people who confuse keeping it real with keeping it true because the two are most definitely not the same thing:

“This isn’t really what you think it is

That is, if you’re even thinkin in the first place

The first place isn’t always the winner, and winnin isn’t everything

and this is not a race

I am not a android I am not a mongoloid

I am not annoyed by the void in your brain

This is not a trick son, you are not a victim

You are just a man b-boyed out the game – let me explain

Abstract are you fresh? (Ain’t nobody fresher

But it’s hard to get around without some clown tryin to test ya

Acey are you dope?) Dopest in the world

I give it to the moms and pops, I give it to the boys and girls

(Oh so you a family man?) Aren’t we all (aren’t we all)

Yes we are (trying to make jams man and expand my repertoire)”

As if the truth of “All Balls Don’t Bounce” wasn’t already self-evident, this re-release goes the extra mile by including a bonus CD of fourteen tracks, from remixes to spoken-word interludes (like the “Headaches and Woes Intro” quoted at the start of this review) to material that’s never been heard before – AND four music videos as part of the enhanced content. Truly an album that not only defies the haters who try to place limits on what rap is and can be, let alone who can hear it and appreciate it for the art it is, Aceyalone’s “All Balls Don’t Bounce” was not only ahead of it’s time for 1995 but still timelessly brilliant in 2004. Even as millions of holier-than-thou rap artists and cultural interpreters proclaim what hip-hop culture is and isn’t, Aceyalone’s album is a bigger middle finger to the establishment than Stone Cold Steve Austin flipping off Vince McMahon on the Titantron. Some rappers just talk good game, while others throw away the board and play by their own rules. They say even Jesus Christ was hated on by the Romans, so by all means let the first “keep it real” hip-hopper without sin cast a stone upon Aceyalone. A rolling stone gathers no moss though, and all balls don’t bounce.