You can’t say he didn’t try. Raymond Scott is the persistent type. He’s taken repeated shots at hip-hop fame, and today, going by the name of Benzino, he is a well-known figure in the rap game. Although some people would argue that he’s more infamous than famous. When talking about Raymond Scott, you can’t avoid touching upon his involvement in the journalistic fiasco the world’s biggest hip-hop publication, The Source, experienced in the mid-nineties. In 1994, his friendship with the magazine’s founder, fellow Bostonite David Mays, led to a dispute that caused several prominent staff members to resign in protest. After they had refused to promote his group, The Almighty RSO, with favorable coverage, writers were intimidated by Scott and his crew, while Mays, who at that time wasn’t part of the editorial staff, wrote and published an article on the group behind his staff’s back. This not only led to a severe braindrain at The Source, it also set the precedent for the following years, as the magazine began to lose much of the critical awareness that had made it the number one hip-hop publication in the first place.

Since then, The Source has plugged Scott, who advanced to the status of official co-owner in 2001 with seemingly no financial investment, more shamelessly with each year, to the point where you already expect to come across something relating to Benzino and his various endeavours when browsing through the magazine’s pages. When the rapper changed outfit in the late nineties and formed the Made Men, Mays again lost important staff members who disagreed on how the group was to be covered, and when Benzino went on his much publicized crusade against Eminem in 2002, The Source served him as a platform.

The irony in all of this is that these shenanigans not only tainted The Source’s credibility, they also cast a shadow of doubt over most of Raymond Scott’s recordings. In the case of The Almighty RSO, people who were aware of what was going on were almost forced to question the group’s artistic credibility. What were they afraid of? Not being able to get any other coverage? Being exposed as wack? As our own editor-in-chief already pointed out in his review of “The Benzino Project”, “RSO despite all their controversies were never a TALENTLESS group, just one who got ahead because of their connections.” We’ll never know how far they would have gotten without those connections.

One thing many Benzino critics fail to acknowledge is that RSO were Boston hip-hop pioneers. Alongside acts like Roxbury Crush Crew, Fresh To Impress, Body Rock Crew, TDS Mob, Disco P & The Fresh MC, Top Choice Clique and Rusty The Toejammer, The Almighty RSO Crew was among the first to release rap songs in the Bean, among them “To Be Like Us” and “Call Us the All” in 1987 and “We’re Notorious” in 1988. According to sources on the net, they won the 1986 ICA B-Town Rap Battle, where also a young Edo (then a member of Fresh To Impress) participated in. When asked in an interview who he considered the founding fathers of the Boston hip-hop scene, Akrobatik answered: “Initially I would think of RSO Crew who were from here and making any type of noise. Locally, if I turned on the radio, those would be the guys that I would know who they were and follow their songs. I’ve definitely been checking them out from the beginning.” This was when hip-hop was just starting to set foot in Boston inner city neighborhoods like Roxbury, Dorchester, Mattapan, South End, Mission Hill and Jamaica Plain.

In that respect, there was little wrong with the article in question. In fact, it could be seen as a tribute to the magazine’s history as ‘The Source: Boston’s First and Only Rap Music Newsletter’, starting as a one-page xerox copy Mays and cofounder Jon Shecter published from their Harvard dorm room. Even as the newsletter turned into hip-hop’s first serious magazine, The Source remained in Boston until headquarters were set up in New York in 1991. Clearly, if Mays would have wanted to give Boston some shine, he’d been better advised to feature different acts rather than focus on his buddy’s group and play games with his staff. But without knowing of Mays’ dubious intentions, ‘Boston Bigshots’ (The Source 11/94) reads like a insightful write-up on the struggles and set-backs any local hardcore hip-hop group could have encountered back then. To many acts under hip-hop’s bipolar hegemony, New York’s and LA’s dominance during those years was a bitch. Even getting your hometown to root for you was hard. And to be heard beyond your city’s limits, you had to be twice as good. Just ask Philly.

As Mays put it in 1994, “In many ways, the RSO story is not an uncommon one, as thousands of young people across America are continuing to bet their lives on the pursuit of a career in the music business. (…) And hopefully, their story is one that the thousands of young people who dream of making it in the rap game can learn from.” And indeed The Almighty RSO’s trials and tribulations mirrored many inner city rapper’s bumpy road to stardom. In 1988, a member of their extended crew, Big T, was shot. In 1991 Rock, a 17-year old MC who had just been added to the line-up, was stabbed to death. By then, the group had been able to secure a deal with Tommy Boy. But their 1992 single “One in the Chamba” got caught in the crosshairs of anti-rap forces. Right-wing figurehead Oliver North and Jack Thompson, the Florida attorney who took the 2 Live Crew to court over a little bit of profanity, assisted the Boston Police Patrolman’s Association (BPPA) in pressing charges against Time Warner, Ice-T and RSO, based on a state law that prohibits the distribution of material that “advocates, advises, councils or incites assaults on any public official or the killing of any person.” Ironically, “One in the Chamba” had been inspired by two young men who had died at the hands of the Boston police.

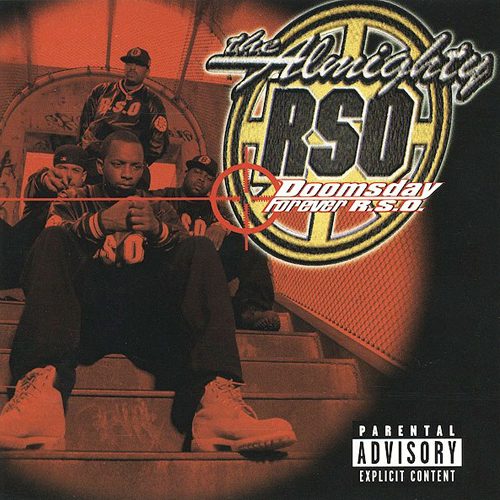

Shortly after the ensuing controversy, RSO were dropped from Tommy Boy. Fast forward to 1996, when the Roxbury Street Organization was finally able to release its debut album as a joint venture between Scott’s and Mays’ Surrender Records and James A. Smith’s indie powerhouse Rap-A-Lot. These connections may have been crucial in enlisting the help of Faith Evans, Mobb Deep, MOP, Cocoa Brovaz and Eightball & MJG, but upon closer inspection, all these cameos actually make sense and don’t seem to have happened solely for the sake of adding star power. Even “You Could Be My Boo” starring Faith Evans wasn’t your typical mid-’90s crossover single, its rugged romance aligning it closer to “Me & My Bitch” than to “Big Poppa”.

Production duties were split between Rap-A-Lot’s in-house beatsmiths Crazy C and John Bido and RSO’s own production outfit The Hangmen 3 (including Benzino and DJ Deff Jeff). Notable outside contributions came from Mobb Deep’s Havoc, Suave House’s Smoke One Productions and Kay Gee from Naughty By Nature. While the album probably sounds too polished to appeal to fans of the trademark East Coast sound, pound for pound it’s just as hard and heavy. And it possesses one understimated quality. While rap acts often struggle to underpin their tales with fitting soundtracks, RSO know which type of beat goes with which type of song. “Summer Knightz” succeeds in copying Ice Cube’s “It Was a Good Day” formula with a breezy Isley Brothers sample and relaxed lyricism from E-Devious (“No cops readin’ me my rights / I like those type of summer nights”) and guest Tangg Da Juice (“Hit the park, we gettin’ bit by bugs / but I guess that’s better than gettin’ hit by slugs”). “Sanity” samples The SOS Band, whose airy keyboard textures and smoothly sailing rhythm section echo the peace of mind Tony Rhome and company long for:

“Buildin’ up inside is enough shit to hurt ya, it’s torture

when your mind tries to desert ya, no one to support ya

For some of y’all life has been a fantasy

and I been livin’ up in hell, nigga, lookin’ for my sanity”

The darker side of “Doomsday: Forever RSO” is represented by various posse cuts. “One in tha Chamba” updates the controversial track with appearances from New Yorkers MOP and Cocoa Brovaz. “Quarter Past Nine” invites local talent to rip a monster beat courtesy of The Hangmen, while “Illicit Activity” injects a heavy dose of Southern gangsta funk while welcoming everybody’s favorite Memphis delegates, Eightball & MJG.

A classic Ennio Morricone theme sets the melodramatic mood in “Doomsday Intro”, blending nicely into “Forever RSO”. While Benzino’s repeated “RSO forever” is a little bit like Large Professor shouting “Main Source forever” on “Bonafied Funk” only to bounce shortly after, “Forever RSO” is a lesson in autobiographical songwriting on the hip-hop tip and remains one of the rare rap songs to successfully sum up an individual act’s history. It goes beyond the usual boasting or whining, as each member takes his turn in the narration, relating the roller coaster ride that was their career, while producers John Bido and Pee Wee provide their flashbacks with a cinematic score worthy of THX. But most importantly, every feeling comes across as sincere, from the optimism of E-Devious’ “Now it’s ’89 and the strength is like a million / and we were so organized you would think we were Sicilian / I had this feelin’ that we’s about to blow / we got Rock, Tommy Boy, plus a dope fuckin’ stage show” to the defiance of Tony Rhome’s “Hooked up with Tommy Boy, they tried to play us / but fuck em, we don’t need no fuckin’ favors / they bitched up, switched up over controversial lyrics / when controversy’s something my crew lives with.” “Forever RSO” is so well executed, you’re even willing to forgive E-Devious for his arrogant and ignorant “We still seein’ courts / cause we beat these writers down from The Source.” Even David Mays, who employed these very writers, makes the family portrait, as Benzino dedicates the song to “my nigga Go-Go Dave, cause without him none of this would be possible.” So I heard.

Despite the burden of its genesis, “Doomsday: Forever RSO” is a well orchestrated piece of work. Not every track is on the same level, but the best are stellar, and the worst are at least okay. Raydog is limited as a wordsmith, but possesses an interesting delivery that charges his lyrics with authority, Tony Rhome’s high-octane flow is hard to contain yet charismatic, while E-Devious is clearly the most accomplished MC of the three. But it’s their combination that makes RSO worthwhile, as each member brings something unique to the table. And let’s not forget DJ Deff Jeff, certainly an anomaly in 1996, when DJ’s had long faded from the standard hip-hop line-up. So even though they were busy building their rep as Boston bad boys, there was still some old school up in RSO, that’s why Tony Rhome’s “Killin ‘Em” is a straight battle track. That’s why several songs project a prudent image (“Keep Alive”, “Gotta Be a Better Way”, “Sanity”, “Summer Knightz”). Like in the movies they quote from (_Miller’s Crossing_ and _A Bronx Tale_), there’s a moral to the stories “You’ll Never Know” and “Keep Alive” tell.

The album comes full circle with the closing “We’ll Remember You”, where each rapper remembers a lost crew member, from the deceased to the locked up, and where the hook is replaced by further reminiscing and a heartfelt “We’ll remember you.” By then, it becomes clear that the remaining members of RSO virtually have lived to tell it, and that “Doomsday: Forever RSO” is the place where they tell it, turning this album into a testament to these Boston pioneers, even though (or exactly because) it remained their only full-length. But in its singularity it achieved what many rap albums set out to do but few achieve – to bring the past to the present.