In the early part of the 20th century (a period loosely defined as coming after World War I and continuing through the 1930’s) African-American arts experienced a boom period which came to be called the Harlem Renaissance. Harlem was the area which was chiefly home to the eclectic mix of artists, poets, musicians and writers who brought not only greater recognition to the cultural voice of the disenfranchised in the United States but to the cultural influence which had been silently shaping all aspects of the American mainstream to date. This cultural explosion also brought in to sharp focus the natural distrust of said artists for their white admirerers; happy to profit from the “hipsters” who came to Harlem to dig the vibe but fearful of their intention to exploit these arts or try to claim them as their own. It was the birthing grounds for many movements which would shape the 20th century: black nationalism, civil rights, the NAACP, the list goes on and on.

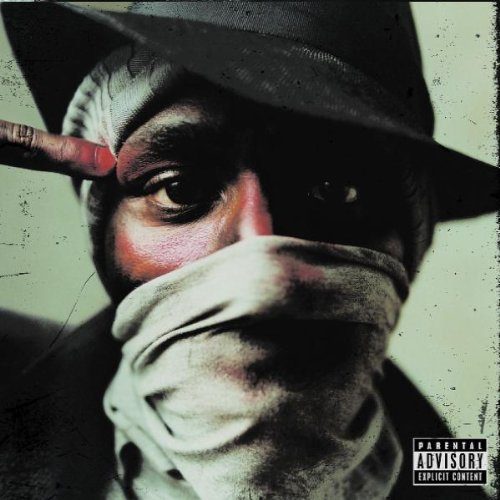

Born Dante Smith in 1973, the artist known as Mos Def became the de facto leader of a Brooklyn Renaissance. Def was definitely a renaissance man in his own right. At a young age Dante was already a successful actor, appearing in television shows such as “You Take the Kids” and “The Cosby Mysteries.” While it was his first commercially successful creative outlet, it was far from his last. As early as 1996 Mos Def was making guest appearances with De La Soul in concert and on remixes, and by 1998 he had formed the group Black Star with partner in rhyme Talib Kweli. Besides being a seminal hip-hop classic, the name of the album and group was also an assertive indication of his heritage to the Harlem Renaissance; given that Marcus Garvey’s founding of the Black Star Shipping Line is considered to be one of the Renaissance’s many definitive moments. From there Mos Def exploded into every art form imaginable – starring in Hollywood movies like Bamboozled and Brown Sugar, hosting and co-producing HBO’s “Def Poetry” and releasing his classic solo album “Black on Both Sides” among others.

As Mos Def’s popularity continued to rise, he experienced the same harsh scrutiny that Harlem Renaissance artists did during their heyday. Mos Def did not shy away from being controversial though. If anything he incited as much as he was insightful, proclaiming in song that “Elvis Presley ain’t got no SOUL; Chuck Berry is rock and roll” and defying his critics to prove him wrong. Like Common’s statement about “coffee shop chicks and white dudes,” Mos Def seemed to revel in antagonizing the very hipsters who wanted to ride on the Black Star line themselves. Regardless if you agreed with his hostility or not he made a valid point that could not be ignored – black musicians throughout the 20th century had been shortchanged, hoodwinked, and straight up robbed of everything from their publishing to their very identity by a white-owned and controlled music industry. Mos Def wasn’t having it. Def felt the only logical response was to form Black Jack Johnson, a collective of modern era black artists like Bernie Worrell (P-Funk) and Doug Wimbish (Living Colour) to reclaim rock music for it’s rightful heirs. He continues to decry artists which he perceives as robber barons of black soul like Limp Bizkit, and makes no apologies for it. Mos Def is a lightning rod for his Brooklyn Renaissance, striking as often as he gets struck, but always seeming to emerge unscathed and continue to be influential both in and outside black culture. If anything being so outspoken only makes him more popular to the very audience he no doubt openly distrusts.

“The New Danger” addresses both his internal and external issues as he continues to preach, teach and reach out from his native Brooklyn streets. Def makes no bones about the fact that one of the biggest dangers for hip-hop music and culture is the fact it continues to be exploited by giant entertainment corporations which have no interest other than their own bottom line. Jay-Z’s “The Takeover” is reworked into the even MORE incindiary track “The Rape Over,” and Mos Def vents his utter dissatisfaction over Jigga’s growling bass and drums:

“Hey lil’ soldier is you ready for war?

But don’t ask what you fightin for

Just hope that you sur–vived the gunfight, the drama, the stress

You get in the line of fire, we get the big-ass checks

You gettin your choice of pimp – make your choice and fall in

This is ho stroll B.I., take that cock in your be-hind

Beatch – hit the streets and perform for us

Ho hard and bring it on to us, fucker

I let you sip cups of Army, get a Mercedes

And kick back and let you pay me, my mack is crazy

I leave the, knife and fist fights filled with glamour

Yeah, take a picture with this platinum plate of sledgehammer

We over-do it add the fire and explode it to it

We’re so confused think we run rap music

MTV, is runnin this rap shit

Viacom, is runnin this rap shit

AOL and Time/Warner runnin this rap shit

We poke out our asses for a chance to cash in”

Like he always does, Mos Def is making a point that’s worth discussing, whether you agree with him or not. There certainly IS a danger of corporations raping hip-hop over and over again to the point it’s no longer culturally or musically distinctive. Not every track on Mos Def’s album has such a barbed point though. The Kanye West produced “Sunshine” is like the title itself – a ray of bright light peaking through dark clouds to warm hearts and souls. Mos Def exhibits a sensible approach to his urban poetry that shows why he was so natural to be involved in “Def Poetry.” His intent is not to overwhelm you with overly complex words or flows, but to use his naturally rich voice to make simple statements with compound meanings. If a picture is worth a thousand words, a thousand of Mos Def’s words paint equally vivid pictures, tempered by his sterling breath control and a clever wit that’s not as brash as a Mad Skillz punchline but still just as effective:

“I don’t hate players, I don’t love the game

I’m the shot clock, way above the game

To be point blank with you motherfuck the game

I got all this work on me, I ain’t come for play

You can show the little shorties how you pump and fake

But dog, not to Def, I’m not impressed

I’m not amused, I’m not confused, I’m not the dude

I’m grown man business, I am not in school

Put your hand down youngin this is not for you

On my +J.O.+ with beats by Kan-llello

My name on the marquee, your name off the payroll

Style fresh like I’m still a day old

And it’s been like that since the day yo

I’m on time with a Roley or Seiko

Step on deck, your neck do what I say so

Get up or get out, get down or lay low”

“The New Danger” encompasses as many different musical styles as Mos Def does arts. He’s just as willing to kick some stripped down Rick Rubin-esque “Ghetto Rock” as he is to pump hard guitar riffs on “Zimzallabim.” You’ll find him taking hip-hop to a land of smoke filled cafes with soulful singing on “Blue Black Jack” featuring Shuggie Otis or swinging jazz on “Bedstuy Parade & Funeral March” with Paul Oescher. The hip-hop has not been left out though, as he fills the album with his razor sharp raps on tracks like the Minnesota produced “Close Edge” and the Molecules laced “Life is Real.” What’s really real is Mos Def’s fearlessness in the statements he’s willing to make, addressing the global socio-economics of “War” (which can also be read as an indictment of George W. Bush) or get down to basics as “The Beggar” who just wants his woman to hear his pleas for love and affection. The range on “The New Danger” is as broad and deep as the Brooklyn Renaissance itself, and on this album Mos Def proves he is worthy of being the 21st century Leader of the New School – too cool.