Making people understand is hard work. How do you relate something that’s on your mind to other people in a way that they understand where you’re coming from? It’s a challenge a lot of professionals face every day. Salesmen, teachers, journalists, lawyers, businessmen, brokers, policemen, politicians, and just about anybody in a managerial position. Whether it’s explaining yourself or explaining certain facts or tasks, you need communication skills. I’ve always viewed rappers as being in a similar position. Arguably, any artistic expression can be seen as an attempt to communicate with the outside world. But rappers by definition are public speakers. They have something very important to tell you. You can hear it in their voices. They beg you to listen. True, they rarely actually beg you, instead they make it sound like it’s a privilege to listen to them, but ultimately the way they raise their voices, the way they come up with interesting things to say, or interesting ways to say things, betrays their deep need to find an audience. That’s why they scramble to take the floor, denying competition the right to be heard. That’s why microphones get mentioned so often in rap songs. Whoever has the mic, gets to talk, the rest listens. Facial expressions, hand gestures, fly gear, expensive jewelry, flashy videos and dope beats aside, when it comes down to it, all rappers have is their word. In the beginning of every stellar rap career, there was the word. If you don’t have a way with words, forget about having a rap career.

Since rappers in action are all talk, it’s that talk that determines if they come across credible and convincing. At any given point in time you have sceptics in and outside of hip-hop doubting the words of rappers. It comes with the job. A convincing rapper and a doubtful audience, they go hand in hand. If you’re trying to convince people of something, don’t be surprised if you’re questioned. If it wasn’t your aim to get people to understand in the first place, why did you even bother to make sense? Because you wanted to be believable. You were looking for approval. You wanted to make yourself heard. That’s why you opened your mouth. Because usually society doesn’t listen to folks like you. You’re nobody important. A lot of times, not even your family and friends listen to you. But as soon as you begin to rap, that’s saying listen up, look at me, I’ve got something to say, and I’ve come up with all these clever rhymes just so you pay attention to what I have to say. If you’re a rapper, what you state in your raps becomes official. It’s a speech addressed to anybody who happens to be around to lend you an ear. Rap is not preaching to the choir. Rap is rhyme and reason. Rappers are condemned to communicate. And they better be good at it. But what makes a good rapper, one you’re inclined to believe? This rap fan here says being able to anticipate objections. Rappers who fully understand their job are prepared to overcome scepticism from the moment they sit down to write lyrics. And until the rap is recorded, all measures should be taken to sway the listener. A coherent argumentation, accurate observations, a refined rhetoric, a clear diction, a measured emphasis, a confident delivery – feel free to complete the list with whatever terms of Greek and Latin origin populate the field of language. As KRS-One put it many moons ago: “It takes concentration for fresh communication.”

Without that basic mechanism, rap would not be what we know it to be for almost 30 years. But as much as I admire rap for what it is, sometimes I’m tempted to reflect on what it could be. In the shortest of terms, I often feel that the rapper’s ego stands in the way of a more substantial content. Few rappers seem to be able, let alone willing, to look further than the tip of their nose, especially US-American rappers and those within their realm of influence. This goes for almost everyone, past and present, legend and newcomer, indie and major, male and female. If there’s something wrong with this music, in a very general but at the same time fundamental way, it’s that rap is a neverending ego trip. While I’m the first to acknowledge that popular music reflects the self-centered society we live in and that the quest for fame is deeply embedded within rap’s genetic code, I think less ego-tripping would result in a more creative and meaningful output. This not the same old lament about how rap music is negative and materialistic, it’s a plea for more personal, more reflective, more detailed, more inventive, more original writing.

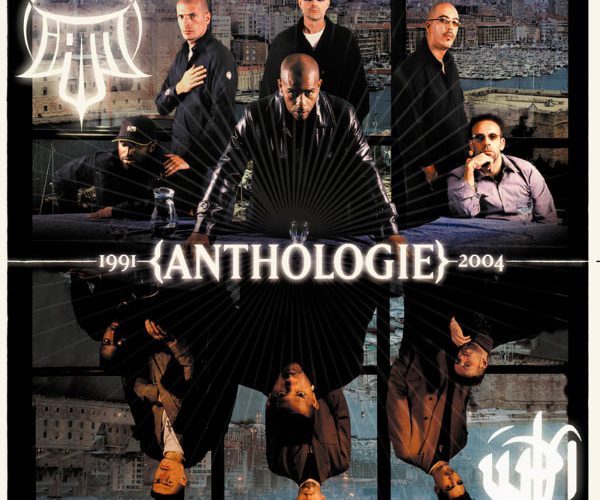

I didn’t realize something was missing in US-hip-hop until I mustered enough courage to compare it to the one closer to home, to European hip-hop. When you’ve become as attached to American rappers as I have, it’s not easy to second-guess their standing. But it can be a healthy process to realize that the people you listen to so intensively choose to limit themselves in their expression. The French rap group IAM is usually among the key witnesses when I make the unpopular argument of the different nature of European hip-hop. And while my argumentation quickly falls apart in many individual cases, IAM is the study case that is prone to prove my point. No other European rap act has lasted as long. A look at the cover of its career retrospective “Anthologie 1991-2004” reveals that 15 years after its inception, this crew still consists of the same six people. That alone is a major achievement, but a mere detail in light of the fact that this compilation is the most detailed look at European hip-hop you can get without asking Matt Jost for a mixtape.

So here I am, trying to convince you of my opinion on a rap group who in turn tries to convince me of their opinion on a myriad of things. The fact that they rap in French and my review is in English while neither of those is my native language doesn’t make it any easier. Things get even more complicated upon revealing that IAM stands for Imperial Asiatic Men. If you remember a time when rappers were affiliated with the Five Percenters and similar spiritual-political movements, that name will definitely have a familiar ring to it. Established in the late ’80s, IAM were a product of the times, influenced by trailblazers such as Rakim and Big Daddy Kane. Stays in the States solidified their knowledge of hip-hop and Afro-American culture. But instead of merely copying what they had been exposed to, IAM put their very own spin on the medium rap and the message it carried. They drew heavily from the sights, sounds and scents of their hometown, Mediterranean Marseille, a multicultural melting pot with Italian, Spanish and Maghrebian influences. One of IAM’s rappers, white, of Neapolitan heritage, called himself Akhenaton, after an Egyptian ruler, the other, black, of Madagascan descent, called himself Shurik’n Chang-Ti, in tribute to his reverence for Asian culture, martial arts in particular. Reflecting the group’s multiple influences and interests, their music boasted an impressive albeit often confusing amount of geographical, mythological, spiritual and historical references.

But the historical décor couldn’t obscure the fact that IAM’s music was always grounded in reality and the present tense. True to the spirit of their era, they became spokesmen for the underprivileged, the second and third generation of African immigrants, young people who didn’t at all feel represented by French society, politics and culture. “Because,” as IAM put it, “we exert more influence than politicians / over the brothers and sisters tired of these cynical characters.” Being from peripheral Marseille instead of Paris contributed to IAM’s outsider status, an image they used to their advantage, referring to their home as the Côté Obscur (Dark Side) and turning Marseille into “Planète Mars,” staging an alien invasion with their 1991 debut “…De La Planète Mars” (“…From Planet Mars”):

“Is Mars really the god of war?

Indeed, war is declared on planet Earth

Instant invasion on hertz frequencies

is the first weapon of the Martian divisions

Destruction, because France is a whore

who dared betray the inhabitants of Planet Mars”

IAM practiced what they called a “Hold-Up Mental” (“Mental Hold-Up”), fighting the power with words, as is the way of the rapper. In that respect, IAM were the French branch of a movement spearheaded by the likes of Public Enemy, Boogie Down Productions, Eric B. & Rakim, Paris, Ice-T and Ice Cube and can be compared to today’s dispersed rap resistance (Immortal Technique, Mos Def, Jedi Mind Tricks, dead prez, The Coup). What sets them apart from most of the aforementioned is that in IAM the rapper isn’t automatically the leading man in his raps. Akhenaton and Shurik’n were keen to write from different perspectives, to think about the world in general, not just their own place in it. The quality of the songwriting was extraordinary from the very beginning. “Tam-Tam De L’Afrique” (“African Drum”), released as a single and accompagnied by a video clip, remains one of Europe’s most important hip-hop songs of all time, depicting slavery from an African perspective:

“Standing on a podium, crammed like livestock

swaying from left to right like straws

They drummed into them that their color was a crime

robbed them of everything, down to their most intimate secrets

Pillaged their culture, burned their roots

from the south of Africa to the banks of the Nile

Under the flag of the tyrants

those who have a block of granite instead of a heart

They mocked the tears and sewed terror

among people who were hungry, cold and afraid

who dreamt of running the peaceful plains

where magnificient gazelles jumped for joy

Oh how beautiful it was, the land they cherished

where their labor brought forth nice, fresh fruit

that offered themselves to the golden arms of the sun

flooding the land with its sparks

And while closing their eyes at every whip they received

a voice told them that not all was lost

that they’d revisit those idyllic landscapes

where the drums of Africa still resounded”

“Tam-Tam De L’Afrique” is just one of many highlights in IAM’s career. A fair amount of them has been compiled for “Anthologie 1991-2004.” Akhenaton’s “Une Femme Seule” (“A Lonely Woman”) recounts the hardships of a single mother, preceeding 2Pac’s “Dear Mama” by two years, while Shurik’n’s “Sachet Blanc” (“White Packet”) details the many facets of drug abuse, both tracks reflecting the group’s unique jobsharing. But differing agendas aside, the duo shared one passion, as explained by “Donne-Moi Le Micro” (“Gimme the Mic”), their “Microphone Fiend,” where they portray themselves as mental patients on the loose, hunting down any device that will amplify their voices, rapping into intercoms, snatching Fisher Price recorders from kids, invading TV studios and McDonald’s restaurants. In a similar vein, the rowdy “Attentat” follows the crew on a party-crashing spree. The boastful “Le Feu” (“The Fire”), a classic concert opener, borrows a fan chant from the supporters of Olympique Marseille, with an added twist:

“Hateful parties, we give ’em hell

Cops that are too nervous, we give ’em hell

Marseille’s enemies, we give ’em hell

The word is in our corner, so I do what I want”

By the ’90s, France had become the second-largest market for rap music in the world. Native artists were able to secure a healthy piece of that pie, thanks to pioneering groups like IAM. Starting with 1989’s self-distributed tape “Concept,” IAM had done their part in establishing French hip-hop, but by the end of 1993, they took things to another level with rap music’s first double-CD (or quad-LP), the epic “Ombre Est Lumière” (“Darkness Is Light”/”Darkness and Light”). The most ambitious release in European hip-hop history, it contained not only innovative beats and intricate rhymes for days, it also featured their breakthrough single “Je Danse Le Mia” (“I Dance the Mia”). The George Benson sample and the Michel Gondry video clip aside, a big part of this song’s charm was its tongue-in-cheek retro vibe. Part parody, part nostalgic waxing, “Je Danse Le Mia” is reminiscent of Wyclef’s “It Doesn’t Matter,” as the crew takes you back to the local early ’80s club scene. Critics of IAM’s sudden commercial success were promptly served with the scathing, sarcastic b-side “Reste Underground” (“Remain Underground”).

In 1997, the best-selling “L’Ecole Du Micro D’Argent” (“The School of the Silver Mic”) followed, shipping more than one million units. “Petit Frère” (“Little Brother”) was another memorable single, and it’s not just the Inspectah Deck sample that reminds me that “L’Ecole Du Micro D’Argent” was the album I imagined “Wu-Tang Forever” could have been. Not coincidentally, it also featured a transatlantic collaboration with Royal Fam’s Timbo King, Sunz of Man’s Prodigal Sunn (on the hook) and Dreddy Kruger from Killa Beez. As welcome as such an acknowledgement of European hip-hop on the part of American rappers was at the time, it was evident that the Wu-affiliates’ arms were too short to box with IAM. Still, “La Saga” remains a definite IAM classic. By 2003, IAM were finally ready for the superstar cameo. Unfortunately, Method Man and Redman were even less appropriate guests. If, in the worst case, all you’d walk away with from this best of was Method Man’s line “Meth Man, Funk Doc and IAM / got these half-naked Hollywood hoes on spy cams,” you definitely would have missed what this group is all about. But again, thanks to the fly beat and the energetic vocals, “Noble Art” has become another staple in the group’s repertoire.

But other selections clearly reflect IAM’s place in history more accurately. “L’Aimant” (“The Magnet”), for instance, a story about growing up in the hood (to use US terminology) inspired a feature film (_Comme Un Aimant_). It’s a special kind of revelation to listen to Akhenaton rap, “I could have believed in George Bush, but see / I’m not satisfied with his vision of the USA,” and realize that he’s talking about Bush senior. “J’Aurai Pu Croire” (“I Could Have Believed”) was a reaction to the second Gulf War (“They intervened in Kuwait because of the petroleum and the money / There’s no use for human rights in the home of the Klan”), but IAM made sure they also dealt blows to Saddam Hussein, Israel, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini and the western world.

IAM albums have always been crammed with messages, and this retrospective is certainly no different. Especially for a foreign audience, the tirades can get tiresome. There’s one track, “Demain, C’est Loin” (“Tomorrow Is Far Away”), where each rapper rhymes for four minutes straight, and they made sure the combined 9 minutes found their way onto this double-disc. Even if you get the point, it’s a highly monotonous affair. But that relentless spirit, being obsessed with details, the epic gestures and the eloquence bordering on loquacity are all part of what makes IAM. There can be much appeal in showing resolvement, a fine example of which is “L’Ecole du Micro d’Argent (Version Guerrière),” which they rip with impressive verve. Rap that sounds this hard is rare nowadays. The group’s fourth full-length, 2003’s “Revoir Un Printemps,” may have lacked in that department, but “Stratégie D’Un Pion” (“Strategy of a Pawn”) once again showed IAM at their most determined, over one of those deeply resonating grooves they’re known for, a post-Bomb Squad, pre-Pete Rock wall of sound with dominant drums, their highly original but rock-solid flows always deeply embedded in the tracks.

The optimistic “Revoir Un Printemps” and the new single “Où Va La Vie?” (“Where Is Life Leading To?”) point in a more mellow direction. But one only needs to come back to disc one and the smooth textures of “Red, Black and Green (Sofa Jazz Mix)” to realize that whatever the mission, IAM have probably been there before. From the cinematic approach of “L’Empire Du Côté Obscur” (“The Empire of the Dark Side”), to the triumphant “Independenza” (which marked the promotion of crew member Freeman to the position of a full-time rapper), to “Tam-Tam De L’Afrique” with its subtle sampling of Stevie Wonder’s “Pastime Paradise” (which Coolio later worked into “Gangsta’s Paradise”), this is brilliant hardcore hip-hop, combining the slickness of funk, the melancholy of the blues, the complexity of jazz and the hardness of hip-hop, and at the same time leaving behind oft-treaded territory, embarking on a sampling world tour led by DJ Khéops and producer Imhotep. Ultimately, IAM may have kept up with the times in terms of sound and structure, but they’ve always managed to form and maintain their proper musical identity, to render their creations original. Even if “Où Va La Vie?” shows hints of Kanye West, it’s still distinctively IAM.

Those familiar with IAM’s albums but not their single releases will quickly realize that “Anthologie 1991-2004” packs many extras, often opting for some single version. Only one stands out as being clearly inferior to the original, “Une Femme Seule.” The inclusion of the comical “Harley Davidson” may seem odd, but can be seen as a mockery of clichéed French mainstream pop and rock. The rest is all highly relevant material, testament to IAM’s humanist agenda and urge to fight ignorance and injustice. These guys even get Beyoncé to sing a socially conscious theme (“Bienvenue (Remix)”). This two-disc set reveals two full hours of songs meant to last, 26 cuts crafted with the utmost care. Outside of a handful of American greats, I haven’t heard many rappers combine rhyme and reason, play the parts of poet, philosopher, political activist and reporter with as much ease and class as the duo of Akhenaton and Shurik’n. And as demonstrated in this review and as heard on “Anthologie 1991-2004,” over the course of a decade and a half, there simply hasn’t been another hip-hop act putting out quality material as consistently as IAM.

[Note: lyric translations by the author]