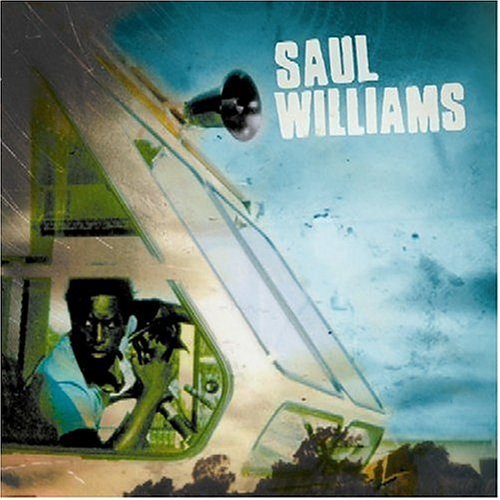

If you haven’t had the pleasure of hearing Amethyst Rock Star” is a lyrical classic that was only held down by an occasional lack of quality music to support Williams presentation, but even with that fact the pure attack of his verbal intellect couldn’t be surpressed. Today the album is an unheralded classic, largely because so few people outside the spoken word scene have peeped it, and even shows like HBO’s critically acclaimed Def Poetry Jam have failed to raise the profile of this movement much outside it’s core following.

Of course nobody gets HBO for free, and if your main means of checking out music is to either hear it on the radio or download what’s hot and new then you’re not really checking for poetry slam inna hip-hop stylee, let alone Saul Williams. Yet with or without a beat, poetry is an expression of one of hip-hop’s most vital elements – a man (or woman) and a microphone. Before artists like Spoonie Gee, Treacherous Three and Sugarhill Gang broke through on the radio you could find The Last Poets and Gil Scott-Heron “rapping” on wax, even though they might not have called it such. Of course to those who study African history (and what better time to do so than now in February, the “black history month” which gets the shaft by being the shortest month of the year) it goes back even further than that, but for the purpose of this review one has to draw the line somewhere. Stylistically one can draw a straight line from the Last Poets controversial 1970’s song “Niggers are Scared of Revolution” right to Mr. Williams modern day self-titled release. Then and now, spoken word poetry has been home to not only the intelligent and articulate but to the disenfranchised who are frustrated with their stature in society and the lack of progress in their community. Williams words can be as blunt as they are beautiful, as “Talk to Strangers” illustrates:

“Nah I wasn’t raised at gunpoint, and I’ve read too many books

to distract me from the mirror, when unhappy with my looks

And I ain’t got proper diction, for the makings of a thug

Though I grew up in the ghetto, and my niggaz all sold drugs

And though that may validate me for a spot on MTV

Or get me all the airplay, that my bank account would need

I was hoping to invest in, a lesson that I learned

When I thought this fool would jump me, just because it was my turn

I went to an open space cause I knew he wouldn’t do it

Where somebody there could see him, or somebody else might prove it

And maybe in their eyes, it may seem I got punked out

Cause I walked a narrow path, and then went and changed my route

But that openness exposed me to a truth I couldn’t find

In the clenched fists of my ego or the confines of my mind

In the hipness of my swagger, or the swagger in my step

Or the scowl of my grimace, or the meanness of my rep

Cause we represent a truth son, that changes by the hour

And when you’re open to it, vulnerability is power

And in that shifting form you’ll find a truth that doesn’t change

And that truth’s living proof, of the fact God is strange”

While Williams flow may seem more traditionally hip-hop in the above excerpt, that’s not necessarily his modus operandi throughout his self-titled presentation. Williams eschews a simple rhyme structure or flowing X number of syllables per bar at will, choosing to go completely beyond any semblence of a rap flow on tracks like “Telegram” and “Seaweed.” On several tracks he even goes beyond the normally perceived confines of spoken word poetry, as he sings his way through tracks like “List of Demands (Reparations)” and “Surrender (A Second to Think).” From one moment to the next, Williams shapeshifts to a different form, which makes his inconsistency a constant in and of itself. Williams at times goes out on a limb where he even seems more in tune with Living Colour lead singer Corey Glover than he does with the acknowledged poets of the scene he comes from. Mos Def talks about “Rock N Roll” but Williams goes to a whole ‘nother level of it on “Control Freak.”

Here again, it’s the music that will challenge hip-hop fans to step into Saul Williams world. While the boom bap of “PG” and “African Student Movement” may feel familiar and natural, the screaming rock of “Act III Scene 2” is more Rage Against the Machine than rap – and not surprisingly Zach De La Rocha provides guest vocals. To those who are willing to see past the last 25+ years of hip-hop and realize that at it’s core today’s modern hip-hop was given birth to by the spoken oratory of a revolutionary era gone by, Saul Williams is just as hip-hop as they come. Sadly this album too will probably go unheralded as millions of hipper-than-thou teenagers search for the next pair of Reeboks and bling bling jewelry.