Just like classic, the term pioneer gets thrown around so often in hip-hop that it has lost much of its original meaning. As time passes, more and more acts escape our collective memory, which contributes to the general impression that today the market is flooded with subpar product, while the past gets glorified as a time when only the strongest rappers survived. In reality the ’80s alone produced tons of average records, and not all of the acts we are kind enough to remember were pioneers, no matter how loosely you define the term. A hazy memory or not being old enough to remember should not be our excuse to hand out pioneer awards to anybody who came before Eminem. If we call everybody we happen to remember a pioneer we not only take the shine away from the ones who are deserving of the title, it also prevents us from establishing some kind of timeline of who did what when.

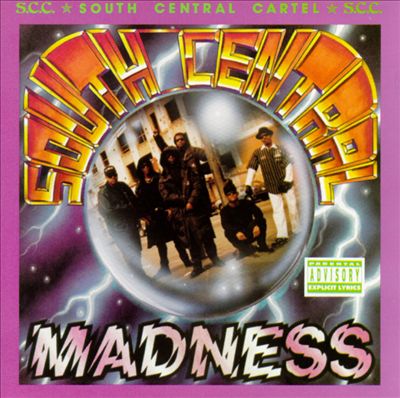

That said, I’m hesitant to refer to South Central Cartel as pioneers. The early days of gangsta rap are a vaguely outlined terrain, so I’m not even sure if this 1991 debut falls into the early days. Then again neither would DJ Quik, who made his first full-length appearance the same year. So if you don’t trust my judgement, take it from AllMusicGuide, who calls them ‘one of the original early-’90s West Coast gangsta collectives to follow N.W.A’s lead […] Despite their lack of commercial success, the group does stand alongside fellow early-’90s West Coast collectives such as N.W.A, Compton’s Most Wanted, and Above The Law as gangsta rap pioneers.’

Be that as it may, there’s one fact nobody will dispute, and that’s the enormous effect “Straight Outta Compton” had on hip-hop. It was an effect that was especially felt in Los Angeles and one that “South Central Madness” speaks volumes of. But what should also be pointed out is that most of the groups that rose to prominence on the heels of N.W.A weren’t cookie-cutter clones designed by the opportunistic record industry, but credible voices of the street. With the exposure rappers from LA had suddenly gained, South Cenral Cartel themselves knew very well that comparisons would be inevitable. Their answer was as simple as it was clever: “It’s not Compton, it’s South Central like a bitch / Another gee with the gaffle gangsta pitch…” went the introduction that acknowledged N.W.A’s pioneering role and at the same time carved out a niche for S.C.C.

Simliar to Compton’s Most Wanted, it would be interesting to know at what point in time South Central Cartel became South Central Cartel. I’d be surprised if their name had nothing at all to do with the success of “Straight Outta Compton.” Either way, these acts not only made out-of-towners pay attention to geographical nuances in LA’s southern parts, they also introduced folks who would have had trouble naming any neighborhoods other than Hollywood and Beverly Hills to the other side of town. For hip-hop itself finally, the Cartel solidified South Central’s status as a breeding ground for talent.

Picking the collective apart to take a look at its individual members produces some rather strange results. First of all, two of them carry virtually the same name, distinguished only by the spelling and an additional moniker. One is called Havoc The Mouthpiece, the other Havikk The Rhimeson. To make matters worse, there’s a third member named Prodeje, which upon listening translates to Prodigy. It’s an odd quirk of fate that both New York and Los Angeles produced a rap duo of Havoc and Prodigy (or Havikk and Prodeje, respectively), the more famous being of course Mobb Deep. It’s a mystery this reviewer has so far in vain tried to solve, but for the record, South Central Cartel debuted one year before Mobb Deep.

While Havikk and Prodeje perform most of the raps, on this album a third rapper named Luva Gee occasionally chips in. Then there’s singer LV, who would go on to assist Coolio on his hit “Gangsta’s Paradise.” Kaos and Gripp were the DJ’s, while Jam-O-Rama co-produced most of the music with Prodeje. Havoc finally held everything together with intros and adlibs and his connection to the music business – his father is Robert ‘Squirrel’ Lester of The Chi-Lites. The legacy of soul is present in S.C.C.’s music as well. The replayed Barry White groove in “County Bluz” isn’t all that great, but “Pops Was a Rolla” is a credible cover (or rather a rap version) of “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” Unfortunately, the much more famous version by Was (Not Was) and rapper G Love E predates this one by a year. The Delicious Vinyl sigee’s verses rank among the most meaningful rap cameos on a pop hit, but Hav and Prod are up to the task as well, and with LV giving a strong performance, the music on “Pops Was a Rolla” does the original justice (provided one can stomach the hip-hop beat plastered over it). Worthy of note however is the difference in the message. The rappers on “Pops Was a Rolla,” being forced to take on the role of the father in their family, end up looking towards their deadbeat dads for inspiration:

“Papa was a hustler, so I wanted to sling

to live up to the name I claim

Mama cried, tryin’ to stop me in my ignorance

but I was grown, I didn’t have sense

All I knew was I was poor, black, broke and hungry

and the streets, they were callin’ me

So I stepped, ready and willin’ to be a gee

to make it easy for my family and me

As for pops, I never got to see the man

but I heard he took matters in his own hand

In the streets he was up on it, well renowned

and if you put him down, yo, then go down

hard; I won’t take shorts, I serve shorts

Pimpin’ hoes and breakin’ hearts

On the for realer my nigga, yo, plain and simple

the man’s back, but now he’s uptempo”

Several other cuts represent the lost artform of uptempo rap, and if you listen closely, the performances reveal the technical aspects involved. Hav and Prod may not leave a blip on anybody’s lyricist radar, but they were damn good rappers. I purposely compliment them as rappers, a sometimes unnecessarily shunned term as everybody strives to join the higher ranks of emcees or thugs (when in reality their profession remains that of a rapper).

Although some would like to lump everything together, a review done by yours truly will always attempt to point out differences as well as similarities. I know this sometimes results in an information overload, but I’ve always viewed that approach as paying an album – any album – the attention it deserves. It’s also the most effective way to counter the “Rap, it’s all the same” or “Gangsta rap, it’s all the same” arguments. So while even I can’t shake the feeling of listening to slightly derivative (or even dated) music when I put on this album, I maintain that “South Central Madness” shows an original and versatile crew. Many themes will seem familiar, but the songs are executed with expertise and line up to display an impressive topical range. “County Bluz” drives its point home, from Havoc’s loudmouth complaints about having (/wearing) the county blues, to Havikk’s, Prodeje’s and Luva Gee’s jailhouse raps. “Neighborhood Jacka” is the quintessential jack move on wax. “Conspiracy” is their “Fuck tha Police,” depicting South Central as a war zone where police are seen as simply another enemy:

“The ghetto is hell, but you bring more

The devil’s in a uniform, fuck it, it’s all out war

The only friend to a brother is a AK

As of now, muthafucka, this is judgement day

cause you roll through our hood and straight jack a nigga

put your knee on our back and cock your fuckin’ trigger”

You wouldn’t expect anything else from an album called “South Central Madness.” The title track is Ice Cube’s “How to Survive in South Central” stretched to posse cut length, which each rapper issuing warnings about the dangers that lurk in South Central, including a female who claims she’s “pullin’ all the cards / I smoke ya and leave you dead with your dick on hard.” How’s that for a rewind moment? Whatever its exact status in the canon of gangsta rap, this debut is nothing short of a blueprint for classic West Coast gangsta rap. The beats are heavily funk-influenced and often virtual prototypes, making you realize just how much West Coast rap owes to Roger Troutman and George Clinton. But don’t think that you won’t hear any James Brown or Average White Band on “South Central Madness” because of that. Most of the album is self-produced, with notable guest production from Wes Word (of Westside Players) and DJ Ace (of Rhyme Poetic Mafia). Also, with two DJ’s in the line-up, you know things will be up to traditional hip-hop standards, at least musically.

On the vocal side, one only needs to listen to the intro to “Conspiracy” (a short sequence of dialogue) to realize the potential of these voices. While not always easy to distinguish, Havoc, Havikk and Prodeje possess some of the most unique voices in the business. Still, “South Central Madness” wouldn’t be trademark LA without the familiar topics. “I Get My Roll On” is a tribute to the six-fo’, with Havikk cruising the city streets and commenting on the sights from the frontseat of his Chevy. “Hookaz” uses Timex Social Club’s “Rumors” to fend off groupies, while “U Gotta Deal Wit Dis (Gangsta Luv)” hopes women will accept the disadvantages of being in love with a gee. (Love songs – rappers don’t write ’em like they used to.)

“Ya Want Sum a Dis,” “Ya Getz Clowned,” “Say Goodbye to the Badd Guyz” and “Livin’ Like Gangstas” are all cautionary musings on the code of the streets. It’s a violent rhetoric boosted by adrenaline-pumping beats, but there’s barely any rage in the rappers’ voices, who deliver their rhymes in an almost matter-of-fact manner, rather than threateningly. Anyone who considers these circumstances carefully will realize that this so-called gangsta rap was and is simply a medium of the streets, not some evil scheme to promote fratricide. And since no community, not even ‘the street’, speaks with one voice, you’re always going to hear different viewpoints on a good gangsta rap album. In this case, “Say Goodbye to the Badd Guyz” is your standard gangbang drama, while “Think’n Bout My Brotha” condemns the mentality that has caused so many deaths:

“You feel guilty so you shoot back and you hit black

And they hit back, another black’s entrapped

Another mother in tears, another kid in the grave

The Lord gave us freedom but till death we’re enslaved”

A careful balance of (expected) ignorance and (unexpected) intelligence prevents “South Central Madness” from being solely exploitative, from being purely entertainment for the rest of us who were fortunate enough not to get caught up in the madness of South Central. Unlike some of today’s rappers, S.C.C. would never think of disrespecting rap as an artform or as a business. They may tell you to your face that “the other level of walkin’ the streets / is way deeper than a nigga bullshittin’ over beats,” but they also know what they have in hip-hop: “Me and my homies have to make it on the city streets / With all the bangin’ and the slingin’ we depend on beats / and dope rhymes that keep us out of chow lines.”

With respect to South Central Cartel’s role in West Coast rap, not everybody would call them pioneers, but some might remember their debut as a classic. Following my initial reasoning, I for once will be stingy with these terms. But while this album may not be most concise musical statement the streets of South Central ever produced, it’s a lively, detailed, action-packed debut from a crew that was able to learn from the best. That includes folks like Eazy-E, Ice Cube, King Tee, Above The Law, Geto Boys, Public Enemy, X Clan and MC Breed, who all get sampled on “South Central Madness.” A combination of (within their category) flawless vocal performances and an (albeit partially borrowed) musical brilliance makes “South Central Madness” an essential listening experience if you’re interested in travelling back to this particular time and place.