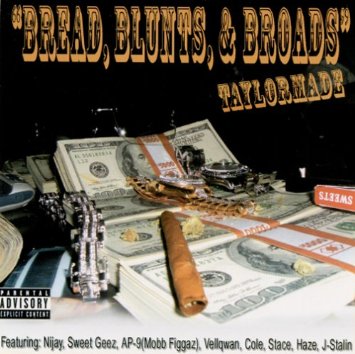

I don’t know if it is coincidence, but the title “Bread, Blunts, & Broads” sounds a lot like Diamond D’s unheralded classic “Stunts, Blunts, & Hip Hop.” With “blunts” as a logical foundation, Taylormade has flipped Diamond’s title around, using alliteration and a modern update by emphasizing “bread” over “hip-hop” for 2005. The similarities don’t stop there, though. The record’s general structure recalls Diamond as well, with Taylormade providing the production and a gang of guests aiding him lyrically. In fact, Taylormade doesn’t even rap on this album; he is strictly a producer and he leaves the words up to his more vocally inclined friends.

The plethora of rappers featured on “Bread, Blunts, & Broads” suit it very well. A couple of artists pop up multiple times, and each artist that comes through provides a unique voice and perspective. Most of the songs are conceptual at least in theory, although rap artists have a universal tendency to lose sight of their narrative thread in favor of shit-talking or general rambling. The record kicks off with “Please Don’t Holla,” an amusing song featuring Nijay, who discusses the tendencies of people to approach an artist by “lying about how we used to chill back in fifth grade.” Taylormade’s production is subtly vibrant but surprisingly lacking in purpose, a mid-tempo beat hardened with horn jabs.

J-Stalin gets the benefit of two solo songs, and he doesn’t trivialize the opportunity. “Sing a Sad Song” and “Take You” feature vivid, engaging verses from the emcee. “Sing a Sad Song” is a general study of his feelings of dissent regarding the ghetto. More than anything, his enthusiasm shines through in his delivery, a frenetic expulsion of hard-edged words. The other emcees fare almost as well, with AP-9 from the Mobb Figgaz providing a heartfelt ode to his “Brother From Another Mother” as the other standout.

Most surprising on “Bread, Blunts, & Broads” is Taylormade’s production, which frequently takes a back seat to the rappers. There are no exceptional lyricists on this disc, but each artist chooses words well, and despite the intended emphasis on the title subjects, they all remain interesting. Taylormade accentuates each track with heavy drums, but the melodic elements are quite understated, and the final product is almost never catchy, usually being merely sufficient as a canvas for the words. Nothing sounds at all wack, and a couple of beats outshine the artists. “Hide the President” features Vellqwan, and is the best song on the album with a loosely disguised Scarface sample and some bizarrely subversive rhymes. “Hustler’s Dream” has a lineup of Sweet Geez, Haze, and Vellqwan, and a heavy piano loop is alternated with satisfying electronic beeps. Oddly, these are the only two examples of the production outdoing the rhymes.

This is a good record, nothing more. As a showcase for Taylormade’s friends, it is more functional than as an example of his own talents. Still, he does not misstep on the entire album, and even the nondescript songs are better than most throwaways. If anything, he suffers from a lack of ambition, and his role appears to be behind his musical peers. Experimentation is often met with distain, but a little something more is needed to separate Taylormade from the rest of the beat junkies across America.