Christopher Wallace and Tupac Shakur share a deeper relationship from beyond the grave than they did while they were alive. They both had records released immediately after their deaths: Shakur’s “Makaveli” coming two months after his demise, while Wallace’s “Life After Death” came only a couple of weeks later. Those albums were already recorded and finished before their sad and untimely deaths, but thanks to the wonders of modern technology, albums they never even conceived of can still make an impact long after they are gone. The irony is that Biggie Smalls lived six months longer than Tupac, yet this is only the second album of unplanned material to come out since his passing – the first being “Born Again” back in 1999. 2Pac albums on the other hand come out almost yearly. Some are not really new material – remixes, greatest hits, live performances – but a surprising number of them are.

The only way one can account for the difference is that Shakur lived life on the edge at all times thinking he could literally see “Death Around the Corner,” and recorded prolific amounts of material while still alive not wanting to waste a single moment – more than could ever be released while he was alive. Wallace on the other hand was a pretty laid back dude. Although he was threatened numerous times by Shakur, his verbal respones were at best minimal and at most extremely subtle. In fact part of Biggie’s continuing appeal long after his death, despite the somewhat uneven track record he had lyrically while alive (martyrdom has made both seem greater in hindsight), is that Wallace had a natural and easygoing charisma in both his persona and lyrical delivery. He could paint a portrait of street violence with natural ease, but he’d rather smoke trees and chill in the breeze. It’s for that reason that there is not a lot of unreleased B.I.G. material to dig up for posthumous albums – he only laid down the rhyme at the right time, when it was needed. In fact there is so little extra Christopher Wallace material out there that “Born Again” consisted almost entirely of raps Biggie did as cameo guest appearances for other artists. Recycled and given an array of new beats and guest MC’s, some made for great listening while others just highlighted the fact that Biggie was truly gone. Enough new Shakur material comes out to convince conspiracy theorists that he must still be alive recording this shit, but for Wallace that will never be the case.

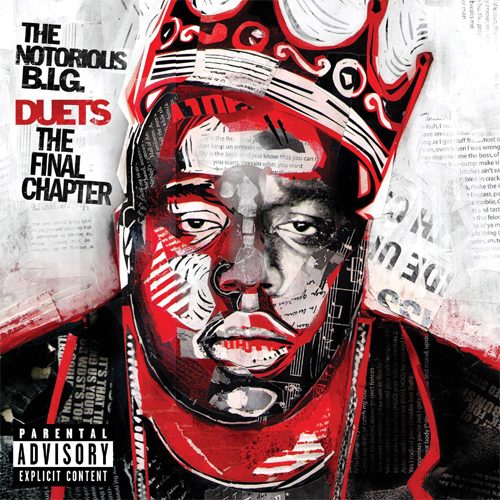

Given the marginally acceptable quality of “Born Again” I was somewhat shocked that Bad Boy Records would actually TRY again to release a posthumous album. The amount of material available has definitely not increased in the six year interim, so it should come as no surprise that on “Duets” you’ll already know the Biggie parts by heart despite the attempt of many star producers and guests to give them new beats, rhymes and life. The most ironic and perhaps most successful of these Duets involves the pairing of two stars who could never have met in real life – the aforementioned Wallace and reggae legend Bob Marley. By combining the mournful Marley track “Johnny Was” with the shockingly morose Biggie lyrics of “Suicidal Thoughts” and a Clinton Sparks track that’s appropriately mellow and moody, the result is the excellent post mortem collaboration entitled “Hold Ya Head”:

“When I die, fuck it I wanna go to hell

Cause I’m a piece of shit, it ain’t hard to fuckin tell

It don’t make sense, goin to heaven wit’ the goodie-goodies

Dressed in white, I like black Timbs and black hoodies

God’ll probably have me on some real strict shit

No sleepin all day, no gettin my dick licked

Hangin with the goodie-goodies loungin in paradise

Fuck that shit, I wanna tote guns and shoot dice

All my life I been considered as the worst

Lyin to my mother, even stealin out her purse

Crime after crime, from drugs to extortion

I know my mother wished she got a fuckin abortion”

One might question making such a deeply dark track the lead single off of “Duets,” but it ranks as a high point among the many collaborations found within this album, despite being pushed all the way back to track 19 out of 22. The album itself is 73 minutes long, including an intro, an outro, and three interludes. The album opens with the track “It Has Been Said,” featuring almost no Biggie vocals other than the occasional “huh” or “what” stabbed in between verses by Eminem, Obie Trice and Diddy. “Spit Your Game” borrows Biggie’s rap from the “Notorious Thugs” duet with Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, but has new lyrics from the Thugsters and adds Twista into the mix. That’s a good decision creatively since they’re all spitting fast but the Swizz Beatz track doesn’t hold a candle to the original. “Whutchu Want” feels more original since it takes some seldom heard lyrics from a DJ Enuff freestyle (pretty hardcore Big raps about sticking ice picks in dicks and giving testicles a kick) with new verses from Jay-Z. “Get Your Grind On” is easily identifiable as Biggie’s “My Downfall” but producer Sean C does a good job of mixing it with lyrics from Fat Joe, Freeway, and the also unavailable Big Punisher, R.I.P.

Mixing one dead artist with another somehow seems less sacrilegeous than some of the other newer and less musically tolerable collaborations. By the time you’re done throwing guests on “Living the Life” it’s hardly a Biggie song at all – Snoop, Ludacris, Faith Evans, Cheri Dennis and Bobby Valentino all have to get a piece and it seems incredibly overblown. You can also say the same about revamping the “Nasty Boy” track into a new song called “Nasty Girl” that features Diddy, Nelly, Jagged Edge and Avery Storm. The best thing about it is that Jazze Pha at least manages to keep his new track similarly jiggy to the original. “Living in Pain” seems like an exercise in proving some sort of point about hip-hop unity by putting Shakur, Nas and Mary J. Blige all on a track with Big. Which one of us believes these four could have gotten along in the studio for more than five minutes? Why not just throw Charli Baltimore and Mobb Deep in the mix to make it even more volatile. There are at least a few collaborations that seem somewhat natural. “Ultimate Rush” jacks Biggie’s chorus from the Lil’ Kim song “Drugs” and pairs him with Missy Elliott, an idea that seems like a natural had he not died just four months before she blew up her “Supa Dupa Fly” debut. The hard pounding Scram Jones beat on “Just a Memory” lifts from Biggie’s “You’re Nobody (Til Somebody Kills You)” and pairs him with The Clipse, which works a whole lot better than you’d think reading it in print. So does the song “1970 Somethin’,” which pairs him with The Game and Faith Evans over an Andre Harris beat. Still these songs can’t justify the ridiculous length other “Duets” on this album go to, such as Lil Wayne, Jim Jones and Juelz Santana all appearing on “I’m With Whateva” or Scarface, Akon and Big Gee all revamping the Bad Boy promotional track “You’ll See” for the song “Hustler’s Story.” One almost has to feel Diddy took a parting shot at The L.O.X. after recently settling with them over publishing rights by completing excising the original and much doper verses of Styles, Jadakiss and Sheek Louch from this song.

To put a bottom line on “Duets – The Final Chapter,” one can only hope the title lives up to the name. While the execution is better than on “Born Again” and this time features more material that Biggie fans might not have heard before, it’s still a hard pill to swallow that so many of these songs remove Big from the natural chemistry he had with the original tracks and place him in environments with new beats and guest stars that don’t fit or make sense. I’ve heard the exact same complaint from hardcore Shakur fans who own the original “Makaveli” bootlegs of many songs that were revamped and remixed for consumption on new posthumous albums and they’re right too. Today’s rap producers take liberties with existing material that would spark a cry of outrage from any other genre. Picture John Lennon’s “Imagine” being stripped of it’s original piano backdrop and suddenly being given a heavy metal riff; or to find his peaceful lyrics interspersed with raps by Young Jeezy. I’m not arguing against musical mash-ups as an interesting experiment for up-and-coming producers like Danger Mouse, or of even people at home with powerful PC’s and music editing tools who like to play the “what if” game. Releasing it commercially and pocketing the proceeds is where I take exception. Even though I don’t venerate Shakur and Wallace with heaps of undue praise simply by virtue of their death, it only seems right that a little more respect be paid to their legacy. For every “Duets” album that comes out an accompanying CD should be packaged in that has the original uncut tracks that the new versions are made from, presented in relatively the same order. That would not only preserve the authenticity of the artist’s original vision but would at least give the public a fair chance to decide if the re-interpretation of that vision holds muster. Doing it better than “Born Again” is a plus, but that doesn’t necessarily mean it ever needed to be done in the first place.