“I came all the way from Cuba just to babalu ya

on a raft to the river, from the river on to ya

Steppin’ like a prisoner who came por el Mariel

with a mission incomplete cause I didn’t kill Fidel

I brought a conga drum and some Celia Cruz records

My mother had me dressed in high-water pants with checkers

talkin’ ’bout, ‘Oye niño, no te haga el porfiado

Grow up and make some records, so you don’t have to live quemado’

So now I’m that kid that brought the Spanglish lingo, baby

with a guayabera shirt and a hat that drove you crazy”

(“Babalu Bad Boy” – 1992)

During what became known as the Mariel Boatlift, approximately 125,000 Cubans arrived in Southern Florida between April and October 1980. Pressured by social unrest, Fidel Castro opened the port of Mariel to anyone willing to leave the country. Within days, a flotilla of fishing ships, boats and rafts arrived from Key West to pick up refugees. The Cuban regime took the opportunity to get rid of elements considered a threat to its Communist utopia, among them homosexuals and mental patients. 23,000 of the arriving Marielitos revealed to immigration officials previous criminal convictions, of which only 12% were actual criminals under United States law. Brian DePalma’s 1983 motion picture _Scarface_ tells the story of a fictional character who is able to hide his criminal past and becomes one of Miami’s biggest drug lords.

Hip-Hop music has paid tribute to ‘Scarface”s Tony Montana on many occasions. One of its most talented vocalists, Brad Jordan, even adopted the moniker Scarface permanently after penning the highly visual and violent song “Scarface” in the late 1980s. Coincidentally, around the same time another rapper laid claim to the moniker, boasting, “Forget Al Pacino, I’m the rap Scarface.” His words notwithstanding, he had no intention of becoming the rap equivalent of Tony Montana. Neither did he cross the Florida Straits with the Mariel Boatlift. Ulpiano Sergio Reyes first steps on North-American soil with his family in 1971 at the age of four. His birth had been instrumental in getting the family an exit visa, and after arriving in Miami, they live in New Jersey for two years before settling in LA County’s South Gate community on Cypress Avenue.

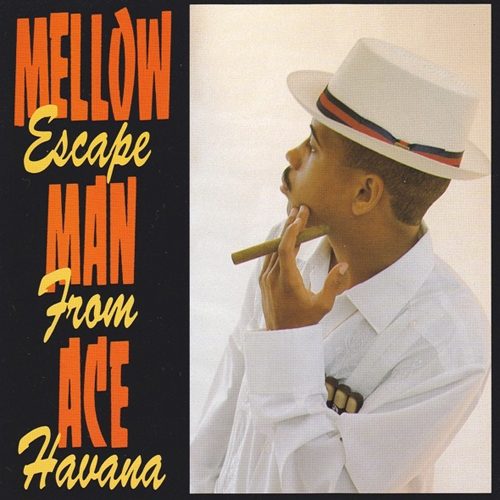

Inspired by old school hip-hop, the Cubanito dreams of a rap career. As a native Spanish speaker, he’s especially intrigued by Mean Machine’s “Disco Dream,” the first ever bilingual rap song. He becomes Mellow Man Ace and forms the group DVX (Devastating Vocal Xcellence) with his older brother Senén, Louis Freese and Lawrence Muggerud, who soon would be known to the world as Sen-Dog, B-Real and DJ Muggs of Cypress Hill. In 1987 Matt Dike and Michael Ross release Mellow’s single “Do This” on their Delicious Vinyl indie. By the time the label enjoys unexpected pop success with Tone-Loc and Young MC in 1989, Mellow Man Ace is signed directly to Capitol Records. “Escape From Havana” was the title of his 1989 full-length debut. It remains a key example for how readily the artform was adopted outside of its prime geographical and linguistic habitat, but at the same time owes a lot to ’80s New York rap. It would be impossible to imagine this album’s slow jams without L.L. Cool J’s pioneering work. “If You Were Mine” and “Enquentren Amor” line up soft 808 stabs, piano sprinkles and an airy “Summer Madness” sample while Mellow, in a soft-spoken tone, plays the reluctant gallant whose love remains unfulfilled: “Feelin’ low and disappointed, girl, it’s easy to see / the only thing that keeps me from you is the coward in me / I know it’s crazy, but love can be real crazy sometimes / but for now I’ll just keep lovin’ you inside my mind.” The bilingual “Radio Edit” of “If You Were Mine” folded the English and the Spanish versions into one, its harder drums, sax and various assorted smooth elements making it one of the suavest, classiest rap songs of its time.

Tony G’s “B-Boy in Love” with its increased BPM rate and less spooky, more soulful atmosphere (thanks to Rufus & Chaka Khan and Isley Brothers samples) finds Mellow slightly more animated, but it’s evident that the LA rapper composed this one strictly for the ladies. Too bad his pubescent poetry pales in comparison to LL’s best-known love letters: “Let me get back ta makin’ goo goo eyes at ya / Okay, I’ll play Caesar and you be Cleopatra / I’ll hold you in my arms and squeeze you real tight / and make lovin’ all through the night.”

Rightfully so, “Escape From Havana”‘s most famous song is “Mentirosa.” The platinum single is a cleverly carried out attempt to cross over into the pop and the Latin market, yet at the same time lives fully up to Golden Age songwriting standards. Tony G underpins the shuffling drum beat with Santana and WAR samples while Mellow exposes the unfaithful lover with what possibly remain the most consistently bilingual song lyrics in all of hip-hop history, often switching languages in mid-sentence (while, reminiscent of N.W.A’s “I Ain’t Tha 1,” a female voice provides commentary):

“Check this out baby, tenemos tremendo lío

Last night you didn’t go a la casa de tu tio

(Huh?)

Resultase, hey, you were at a party

higher than the sky emborrachada de Bacardi

(No I wasn’t)

I bet you didn’t know que conocí al cantinero

(What?)

He told me you were drinkin’ and wastin’ my dinero

Talkin’ about, ‘Come and enjoy what a woman gives a hombre

(But first of all, see, I have to know your nombre)’

Now I really wanna ask ya, que si es verdad

(Would I lie?)

and please, por favor, tell me la verdad

Because I really need to know, yeah, necesito entender

if you’re gonna be a player, or be my mujer

Cause right now you’re just a liar, a straight mentirosa

(Who me?)

Today you tell me somethin’, y mañana otra cosa”

Few rappers have since explored the possibility of bilingual lyrics, which makes “Mentirosa” even more exceptional. Elsewhere, Mellow Man Ace struggles to come up with an equally compelling effort. The Def Jef-produced “En La Casa” relies on the stereotypical structure of late ’80s dance tracks, and as he repeatedly references ‘la raza’, you’re instantly reminded of the 1990 Kid Frost classic of the same name. Johnny Rivers’ “Gettin’ Stupid” is also standard fare, pedestrian late ’80s hip-hop with a dance/pop touch. Still, Ace manages to insert worthwhile bits and pieces, claiming “seniority” and at the same time promoting his “new style or method of rockin’ on a record.”

Throughout “Escape From Havana,” either explicitly or by virtue of his actions, Mellow Man Ace relates that he has something new to offer: “Take a big bite, go ‘head and savor / the new taste the Mellow Man gave ya.” It goes beyond the usage of Spanglish and extends to the musical side of this album and thus ultimately the sabor latino that Reyes seeks to bring to the rap game. On “Rap Guanco,” him and Tony G take you on a trip across Latin America during an extended percussion break. But the great thing about it is that this is not a product conceived to turn a specific demographic into rap fans (although Ace certainly did contribute to that by touring Latin America), it doesn’t feel like an exploitation of Latin styles and attitudes, it feels like hip-hop, just from a slightly different perspective than what you were used to. Still, any aspiring entertainer who was bold enough to claim to have – to put it inoffensively – the ‘bigger balls’ (“Más Pingón”) simply had to be a b-boy.

“It’s somethin’ ’bout the hip-hop, we just can’t live without it / give us a place to be and then we’ll absolutely house it,” he boasts on “Talkapella,” as a West Coast resident and as a Cuban immigrant, remind you. Inspired by hip-hop’s creative power, Mellow Man Ace changes settings, starring in his own Western as “South Central’s fastest rhyme fighter” (on “Rhyme Fighter,” which also seems to contain a jab at Eazy-E), or haunting us as scary “Hip Hop Creature,” accompanied by the album’s main producers Tony G and the Dust Brothers, who take the challenge just as serious, constructing tracks out of single, sequenced, or multiple, stacked samples, some of which would reappear years later, such as the gritty loop that’s shared by “Talkapella” as well as the 1992 KRS-One/Freddie Foxxx duet “Ruff Ruff.” Lest we forget, there’s a respectable amount of cutting and scratching on this album, likely courtesy of Tony G.

“Escape From Havana” is rarely mentioned when classic rap albums of the ’80s are discussed. Admittedly, sonically, vocally and lyrically it’s not up to par with its prominent New York peers, but the real reason for its relative obscurity could be that it may have been groundbreaking in a way that makes it less eligible for elitists and is being ignored for the same reason “Loc’ed After Dark,” “Naughty By Nature” and “Cypress Hill” seem to have faded from the selective memory of hip-hop preservationists – because it attracted audiences you don’t readily associate with hip-hop’s inner circle. Today these people may be in the majority, but back then they were listeners who were more into the music and less into its popularity, not least because hip-hop showing a softer side wasn’t really that popular. They just happened to like a bit of pop in their hip-hop. Even so, this hip-hop critic who’s always been critical of pop influences thinks it’s a good thing that there are no guest singers on this album.

Pop or hip-hop, Mellow Man Ace was willing (and able) to cater to almost everyone except the gangsta segment (very much abiding to ‘Scarface”s closing disclaimer that ‘The vast majority of Cuban-Americans have demonstrated a dedication, vitality, and enterprise that has enriched the American scene.’) He could pen love songs, he could take a lyrical approach, he could be goofy, he could battle, and he managed to find different forms of expression depending on theme or track. Unfortunately, the album title remained an empty promise, as there are no accounts of events of that nature.

These days, “Escape From Havana” may mainly pique the interest of Cypress Hill and Beastie Boys die-hards. Matt Dike and Michael Ross AKA The Dust Brothers even employ later Beasties confidant Mario Caldato Jr. as an engineer on two tracks, but despite the albums sharing year of release and record label, don’t expect another “Paul’s Boutique.” As for the Hill, produced by Grandmixer Muggs, “River Cubano” marks the maestro’s first official production gig, which, although heavily Marley Marl-inspired, definitely lives up to the expectations of an early Muggs beat. As Ace puts it: “In the Tribe he’s the ill Italiano.” Not to forget, Sen-Dog (then known as Sen-Stiff) chips in with a few lines.

Mellow Man Ace later wrote “Real Estate” for Cypress Hill and recorded a second album before leaving the business, which he re-entered in 1999 alongside his longtime compadres on their Spanish album “Los Grandes Exitos en Español,” followed by a couple of indie albums. This year, he’s teamed up with his famous brother to release the anticipated “Ghetto Therapy” album under the Reyes Bros guise. Read more about it in our recent interview.