In December 1998 TIME magazine published a TIME 100 issue titled ‘Builders & Titans – The most influential business geniuses of the century.’ It profiled twenty people who ‘could take an idea and turn it into an industry.’ They were: Henry Ford (automobiles), David Sarnoff (broadcasting), Louis B. Mayer (motion pictures), A. P. Giannini (banking), Charles Merrill (investment), Willis H. Carrier (air conditioning), Stephen Bechtel (construction), Walt Disney (entertainment), Juan Trippe (aviation), William Levitt (housing), Walter Reuther (unions), Leo Burnett (advertisement), Thomas Watson Jr. (computers), Ray Kroc (food), Estée Lauder (cosmetics), Pete Rozelle (sports), Akio Morita (home electronics), Sam Walton (retail), Bill Gates (computers) and – Lucky Luciano.

The latter’s profile begins as follows: ‘He was born and died in Italy, yet the influence on America of a grubby street urchin named Salvatore Lucania ranged from the lights of Broadway to every level of law enforcement, from national politics to the world economy. First, he reinvented himself as Charles (“Lucky”) Luciano. Then he reinvented the Mafia.’ Much has been said about the United States and its fascination with criminals. But for a mobster to make such an important and illustrious list means honoring the business sense of the criminal mind in itself. In her article, Pulitzer Prize winner Edna Buchanan credits Lucky Luciano with a ‘vision of replacing traditional Sicilian strong-arm methods with a corporate structure, a board of directors and systematic infiltration of legitimate enterprise’ and a ‘management style far different from that of his Chicago counterpart Al Capone, who spent more time killing than doing business.’

She goes on: ‘The FBI describes Luciano’s ascendancy as the watershed event in the history of organized crime. After his hostile takeover, Luciano organized organized crime. He modernized the Mafia, shaping it into a smoothly run national crime syndicate focused on the bottom line. The syndicate was operated by two dozen family bosses who controlled bootlegging, numbers, narcotics, prostitution, the waterfront, the unions, food marts, bakeries and the garment trade, their influence and tentacles ever expanding, infiltrating and corrupting legitimate business, politics and law enforcement. Luciano also led the trend in gangster chic. He lived large in a suite at the Waldorf Astoria. Expensive and elegant suits, silk shirts, handmade shoes, chasmere topcoats and fedoras enhanced his executive image. There was always a beautiful woman, a showgirl or a nightclub singer on his arm.’

In 1936, Luciano was convicted of multiple counts of compulsory prostitution. While in jail, he contributed to securing naval intelligence against Nazi Germany and assisted the Allies when they planned to land at Sicily. In recognition of his efforts he was paroled and deported to Italy in 1946, where he died in 1962, not before playing a crucial role in establishing the international drug trade. Buchanan concludes: ‘Unlike so many predecessors and colleagues, he expired of natural causes, a coronary – an occupational hazard common to hard-driving executives.’

Seventy years after his forced retirement, Lucky Luciano’s influence on American society manifests itself, amongst other places, in the segment of the entertainment industry that we call rap music, these days a prosperous enterprise in its own right. Often it is more of an indirect influence, exterted by fictional characters and real-life mobsters, but every fan can name a rapper who hopes to live up to the Lucky Luciano mold of a businessman. Inevitably, one artist even had to adopt the moniker in its entirety, which was the case with a Houston rapper on SPM’s Dope House Records.

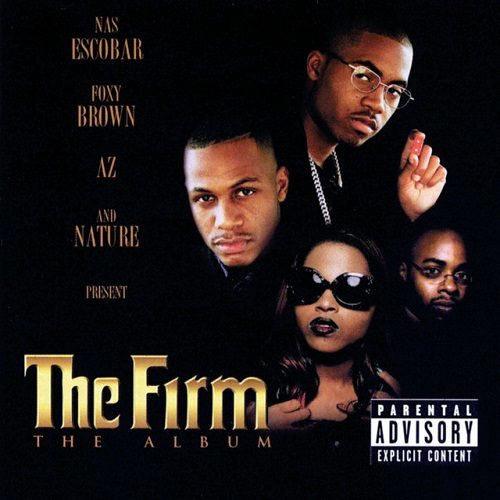

Mid-1990s rap is particularly known for idolizing organized crime both in style and spirit. Remember Jay-Z suited up on the cover of his debut while confessing inside, “Never prayed to God, I prayed to Gotti”? Biggie’s Junior MAFIA? Master P claiming to be “Da Last Don”? Suave House artist Crime Boss? The Clan dubbing as “Wu-Gambinos”? BIG and Jay planning to collaborate in The Commission (a term directly derived from Luciano’s business model)? No other project symbolizes both the aspirations of mob-inspired hip-hop as well as its trappings better than The Firm. Undoubtedly inspired by the Grisham thriller/Pollack movie of the same name, the decision to call a criminal organization a ‘firm’ reflects the idea to run an illegal operation just like any other business, and to achieve legitimacy through a respectable appearance.

Appropriately enough, the story of The Firm begins with an act of betrayal. The foursome of Nas, AZ, Cormega and Foxy Brown spun its first and only tale on “Affirmative Action” off Nas’ second album “It Was Written.” But sometime between being included by Fox Boogie in her ’96 “Letter to the Firm” and the ’97 release of “The Album,” Cormega was replaced by fellow Queensbridge representative Nature. There is more than one side to this story, but the main conflict seemed to stem from the fact that Interscope’s Steve Stoute demanded that Mega sign a production deal while the latter opted for Def Jam. Under the direction of executive producers Nas Escobar and Steve ‘Commissioner’ Stoute he was expelled from The Firm, his bitterness increasing when his debut for the label of his choice, “The Testament,” was shelved forever.

Meanwhile, The Firm received all the attention its line-up demanded. Acting as ‘supervising producers’, Trackmasters and Dr. Dre held equal shares in the score, but it was LES who produced the lead single “Firm Biz.” The song, a predictable pop tune with ex-En Vogue singer Dawn Robinson, flopped, and so did “The Album” with its all-star cast that seemingly boasted everything from lyrical prowess to sex appeal to state-of-the-art production. The title of one of its songs – “Firm Fiasco” – came to symbolize the failure of this first proper Aftermath album. Instead of the expected boost, it was a blow to the careers of all involved and confirmed the suspicions of those who gave post-Death Row Dre little credit and those perceiving “It Was Written” and the transition from Nasty Nas to Nas Escobar as a decline from lyrical prodigy to megalomaniacal mafioso.

Given that it’s one of rap’s admirable qualities to draw from all kinds of sources of inspiration, it is almost expected that such an album makes reference to certain motion pictures. Paired with a general lack of originality, however, the ‘Goodfellas’, ‘Batman’ and ‘Scarface’ impressions are mere déjà-vus. The same with interpolating ’80s hits and reinterpreting them under derivative titles – Cheryl Lynn’s “Encore” becomes “Hardcore,” Teena Marie’s “Square Biz” becomes “Firm Biz,” The Jones Girls’ “You Gonna Make Me Love Somebody Else” becomes “Fuck Somebody Else.”

To prove both his worth to The Firm and that there’s nothing per se wrong with the concept if executed well, Nature remakes Whodini’s “Five Minutes of Funk” into “Five Minutes to Flush,” detailing the five minutes that lie between the feds demanding and gaining entrance. On an album otherwise crowded with arbitrary people doing the hooks, Roger Troutman’s talkbox is the only voice assisting Nate in his narration. And even though he’s the freshman, Nature is the only one in The Firm with adequate storytelling ability:

“About a minute went by, they knocked harder

My bitch went hysterical in shock, slapped her to calm her

.44 cocked the armor, it’s been a long day

Now a raid with jakes playin’ the hallway?

It’s senseless, enter my crib and can’t prevent this

Blockin’ my entrance, tryin’ to knock it off the hinges

Battering rams come in inches, my hoe was buggin’

Throw a fit, puttin’ coke in the oven

Like I’m Larry Davis, the phone rang, some DA bitch:

‘Nature, turn yourself in’ – I didn’t say shit

Knowin’ in my heart I’ma stay rich

It’s amusin’ confusin’ ’em till they lose patience

Try to ease up, calm my nerves with the cheeba

Hopin’ the door doesn’t fall before the ki’s flushed

D’s rush, plus the riot squad

No surrender, no retreat, shit’s deep when times is hard”

Nas, AZ and Foxy Brown all fail to insert some sense into this project. Every Fox verse seems to be sex-related in some way, while Nas and AZ never reach the level of their 1995 duet “Mo Money, Mo Murder (Homicide)” (which can be considered The Firm’s inaugural meeting). AZ regularly proves he is an expert rapper, but catch Fox and Esco just rhyming along with no concept whatsoever in “Hardcore,” add the Trackmasters beat-jacking and you have a song that is as unoriginal as rap gets. Guest vocalists include Pretty Boy, Wizard, soon-to-be Superthug Noreaga, the late Half-A-Mil and Canibus (whose battle raps aren’t that out of place on “Desperados”). But only the inclusion of Dre seems compelling, when alongside Nature in “Firm Family” he assumes a true air of superiority:

“It’s time to give, let the kids live comfortable

Anybody pumpin’ beef between East and West – fuck you

Make moves political, get this revenue

Set examples, respect every individual”

“The Album” is not without ideas worth pursuing, if only they would have been pursued more rigorously. “Firm Fiasco,” underlaid by Dre with plucked and stroked strings and a punching drumbeat, would serve well as an introduction if the rappers would have made an effort to actually introduce themselves. “Phone Tap” is fittingly orchestrated for this somewhat ambitious song, but there’s not much to derive from it other than that somebody eavesdrops on The Firm’s phone conversations.

Musically, Trackmasters Poke and Tone (assisted by Curt Gowdy) and the Doctor (assisted by LA veteran Chris ‘Glove’ Taylor) achieve respectable results whenever they opt for something more original, the former with the Mediterranean violins of “Executive Decision” or the Latin guitars of “Desperados,” the latter with the classy, cinematic “Phone Tap” and “Firm Fiasco.” What “The Album” sorely lacks, however, is a clear vision shared by all Firm partners. Other than the name and the approximate nature of the project, few details seem to be determined. Clearly Lucky Luciano would have had a field day with this mess of a mob.