While it’s not true that divisions of style and intent have always existed within rap music, it might seem that way for anyone born before N.W.A. came through and made people start making distinctions. Pre-’88, the Hip Hop community seemed more unified, in mindstate if not sound. Ironically or not, this Edenic loss of innocence occurred at a time of great creativity, so before the many styles bloomed and forced a fissure in the game, cats from all flavors had mad love for each other. Ice-T toured with Public Enemy, and Stetsasonic, not to mention EPMD and Rakim, Run-DMC and the Beastie Boys. But as each style begat followers, sub-categories formed and gelled, and by ’93, seemed like you were either west coast or east, conscious or gangsta, old school or new. Cats from the Bronx started coming harder while the Native Tongues and their ilk embraced the Jazz Thing, not too mention all the directions the west and south were going. Fast forward to the early-90s and peep that many divisions were even deeper, especially the one between conscious/underground and gangsta/commercial (both largely inaccurate delineations, especially now). Only recently have Kanye and others begun the process of dismantlement with songs like “Jesus Walks,” showing how outmoded and even silly certain subgenres of rap are, especially in a game where acts are far more diverse (as in plentiful) geographically, and arguably artistically, than ever.

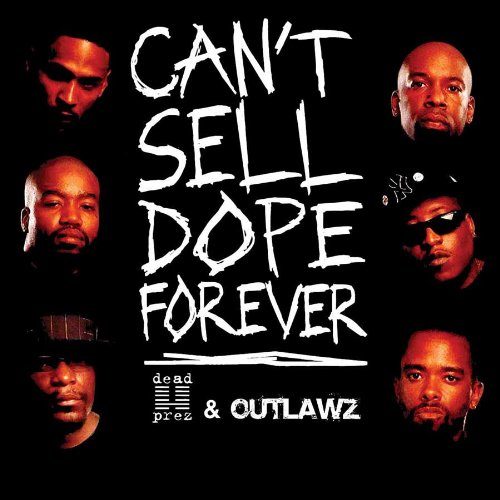

In a similar vain, the political divide of our current climate threatens to forever alienate left and right, and more importantly, poor and rich. But a deeper unification has arisen out of these deep divides, I think, between progressive activists and the multitude of people getting jerked by Uncle Sam. As desperation sinks in on many levels, those most in need of change will rise up the strongest. In other words, revolutionaries and thugs have never looked so much alike. The new collaboration between Dead Prez and the Outlawz exemplifies these cultural as well as the political trends, by first acknowledging and then smashing many of the formerly sacred lines separating those who should and could unite. Their new project is both revolutionary and gangsta, both activist and stubborn, ignorant and intelligent, political and underground. On a deeper level, the project merges an equal desire to both entertain and educate/activate, succeeding in the way BDP’s early albums did. By alternately telling it like it is and offering practical, urgent solutions, “Can’t Sell Dope Forever” makes current radio fare like “Ridin” sound worse than childish… more like irresponsible.

It should come as no surprise that Dead Prez should be involved in this ambitious project, but some may wonder what the Outlawz bring to the table. I have to admit that despite their strong revolutionary origins (Pac’s Thug Life movement was far more complex than most youngin’s care to remember), I never really checked for the Outlawz, mostly out of skepticism for any and all 2nd generation off-shoot groups— big up Nas’ Bravehearts and Mase’s Harlem World—but I gotta say, they came with it on this release. The album seems to have been a true collaboration between the two groups, as both production and vocal duties are shared by everyone. To get a clear sense of the project, one only really needs to listen to the first three tracks, all of them superior. “1Nation” sounds the call of unity, recognizing how silly the antiquated borders between Hip Hoppers are in a time when we are all attacked by the same enemies. The first verse boils down a mindstate into a passionate yet calm manifesto:

“Now we can hop off into some gangsta shit

Or reverse this shit and hit our real enemies

Nigga, you look just like me

What sense do it make killing each other in their streets

Listen up/ all these guns we got between us

We can point ’em the right way and come the fuck up

Dope money and turf ain’t worth your life

Doing it for the struggle, that’s how you earn your stripes”

The manifesto continues (and gets more specific) with the title track, a club-banger that uses drugs selling as a metaphor for, well—selling drugs, selling sex, or doing dirt that isn’t sustainable. The basic message, among many, is: you gotta move on to move up. Here as in every song, there is a perfect compliment between the heavy politics of d.p. with the “Black CNN” tell-it-like-it-is of the Outlawz. More amazingly, the two crews seem to trade off these roles effortlessly. By vividly describing the contradictions and hopelessness of struggle, and following it with real alternatives and encouragement, both groups cancel out each other’s weaknesses (unpalatable conspiracy politics and ignorant nihilism, respectively), giving us a wonderful hybrid.

Track four, “Like a Window,” is perhaps the most effective on the album as stic.man describes a painful love/hate relationship to his junkie brother. The song is refreshing firstly because it looks at the drug problem not from the standpoint of the dealer (the voice usually used by eMCees), but of the abuser, showing us that the drug trade not only wreaks havoc on young males hoping for something better but also on those looking for escape. The second verse begins through the eyes of his brother returning yet again from jail, but quickly morphs into a grand statement for all oppressed people:

“I know its hard coming home to the same old shit

Ain’t nothing changed cause the game don’t quit

The pain inside is still throbbin’

The same conditions that first created the drug problems

Still exist/ and it’s a bitch

Gotta go to the job or starve

Without a gun everyday employees get robbed

And on days off we blow off the crumbs like nothing

Getting high cause a nigga gotta get into something

But we get trapped in a cycle of pain and addiction

And lose the motivation to change the conditions

I blame it on the system but the problem is ours

It’s not a question of religion

It’s a question of power

How did Black life—my life—end up so hard

Why do so much injustice go unresolved

Why do one’s we call governments be the main causes

Behind how all the dope is coming through the borders

Television reporters got the facts distorted

Making scapegoats of every Black youth on the corner

It’s a war even though they don’t call it a war

Its chemical war unleashed on the Black and the poor

And who benefit? The police lawyers and judges

The private-owned prison industry with federal budgets

All them products in the commissary

Tell me who profits/ its obvious

And it’s going too good for them to stop it”

The album proceeds thus, with messages both true and essential. Sonically, the collaboe creates unified and contagious backdrops with Dead Prez’ signature drum machine gun assaults and Outlawz’ g-funk bass grumbles. Once or twice the mix threatens to be a little too uplifting (read: corny), as on “Fork in the Road,” which features sweet acoustic guitar and warm handclaps, veering dangerously close to gangsta lament cliché (a la Pac’s posthumous “Thugz Mansion”). Rarely is this an issue, however, as the beats remain as fresh as the lyrics right to the end. And I still couldn’t help but imagine how much more berserk this album would’ve been if the Outlawz former leader were still around to help out. Late in the album, an announcer on a skit announces that this is, “a takeover, not a makeover.” Flawlessly expressed both in spirit and in execution, “Can’t Sell Dope Forever” is truly what the game’s been missing—and what I suspect Pac wanted all along—a thug revolution.