In 1969 inmates of Rahway State Prison in New Jersey formed a vocal ensemble called The Escorts. They came to the attention of George Kerr, a veteran soulman who put them on his Alithia label, producing two albums with them in 1973 and 1974 (remastered and re-issued together in 1997 by Sequel Records as “Prisoners of Soul”). By the time these albums were recorded, the line-up of the group had changed due to the natural fluctuation in correctional facilities. The recording act The Escorts consisted of seven members. They would record their vocal parts within the prison walls over rhythm tracks laid down previously by Kerr and arranger Bert Keyes in a professional studio. Since after their first album the sentences of three members had been completed, to record the aptly titled follow-up “3 Down, 4 to Go”, the free group members joined their fellow bandmates in jail for the recording sessions. The Escorts garnered considerable commercial success and critical acclaim with their mixture of love ballads and socially aware songs such as “Disrespect Can Wreck,” “Corruption (Man’s Self Destruction)” and “Brother.” But the one song that symbolized their unique position best was the chillingly remorseful, apologetic uptempo plea “All We Need (Is Another Chance).”

20 years later inmates of that same facility in Rahway, now called East Jersey State Prison, set out to follow in the footsteps of The Escorts. But this time the laments coming from behind bars weren’t nearly as melodic. Instead, the hard-hitting rhythm of rap echoed from the prison walls. They called themselves the Lifers Group, a collective of prisoners who perceived rap music as the perfect vehicle to get their message out there. It was the late Dave Funkenklein who brought the Lifers Group to Disney’s Hollywood BASIC label while Solid Productions provided the musical background. But Lifers Group was more than just a compelling name for a rap act with an unusual background.

Lifers Group Inc. had been founded in the 1970s, its membership consisting of men who served life and extended long-term sentences in excess of 25 years. In 1976, the collective initiated a program called the Juvenile Awareness Project Help, which included what would become known as the Scared Straight program. Scared Straight was described as a verbal and visual description of prison life for juveniles available to police, probation, court juvenile agencies, high schools and parents. In what were called ‘rap sessions’ between juveniles and inmates, the Lifers discussed all aspects of prison life in a candid manner, literally trying to scare kids into going straight, hoping to deliver a shock treatment to youths who had become involved in juvenile delinquency and turn them into law-abiding adults.

In 1978, the program was presented to the public in the documentary _Scared Straight!_, which after an initial local success in Los Angeles was nationally syndicated and went on to win an Academy Award for best documentary the following year. An article (‘Scared Straight: A Second Look?’) published by the National Center on Institutions and Alternatives (NCIA) in Baltimore relates:

‘_Scared Straight!_ played to a large and enthusiastic audience. There had probably never been a television documentary like it: the obscene language, the descriptions of violence and sodomy, the passionate intensity of the prisoners, the resonating steel sounds of cell doors slamming shut. “Please don’t make me hurt you,” a lifer spits in the face of a teenage boy, “because if I have to break your face to get my point across, I’ll do it, you little dummy. You’re here for two hours, you belong to us for two hours.” One after another, the prisoners berate, rant, strut, and menace. “I’m bad, you see me, boy, I’m bad,” snarls another. “You see them pretty blue eyes of yours? I’ll take one out of your face and squish it in front of you.” In prison, “the big eat the little.”‘

But the efficiency of programs such as Scared Straight (which wasn’t the first of its kind) was contested by experts. In 1978, a study conducted at the Rutgers School of Criminal Justice concluded that despite rave reports, these drastic methods had no deterrent effect on the youths that were exposed to them. The researchers wrote: “Delinquent behavior arises from a multitude of complex factors; therefore, we believe it is naive, simplistic and unrealistic to assume that a two or three hour visit to Rahway can counteract the long-term effects of all these other variables.” Serious studies indeed seem to show that not only do social interventions of this kind not have the intended effect on experiment groups but are actually likely to backfire.

Despite these sobering findings, programs similar to Scared Straight continue to be in use, as they embody the ‘get tough’ philosophy in regards to juvenile offenders and are an example of a seemingly simple cure for a difficult social problem. Their effectiveness seems to be evident to anybody who can’t be bothered to keep abreast of social studies, plus they cost little and make constructive use of prisoners. The aforementioned article summarizes: ‘It wasn’t only the drama of _Scared Straight!_ that captivated the press and public. There was an almost irresistible allure in the concept of the Rahway program. It had the trappings of a morality tale: hardened convicts, realizing the error of their ways, devoting themselves to saving others from the same bitter fate. It wasn’t only the youths who were going straight.’

And that should be the least contested aspect of such programs. On its website www.wild-side.com Lifers Group Inc. writes:

‘Too often the long-term prisoner and prison brings forth a stigma into the public’s mind of what an incarcerated person is supposed to be. Thoughts of a bestial person without emotion or feelings, immortal, perverted, marked by venality and the classic Hollywood stereotype of a convict whose only thoughts are evil or to get even with society. Our group was founded on many premises and one was to show that this stereotype is just a falsehood. Our desire is to improve ourselves as best we can under the present circumstances, in order that we will leave this imprisonment as better persons than when we entered. We are working towards that all important quality, that is to be useful and productive members of society. We as incarcerated people, seem to be a class that suffers from tremendous discontent without an adequate language with which to register complaints, or to imagine a brighter future for ourselves. The Lifers Group Inc. is trying to improve these sad and desultory endeavors with constructiveness.’

Which brings us to the rap act Lifers Group. In 1993 they followed up their self-titled debut EP from 1991 with the longplayer “Living Proof.” In a way, the Lifers Group combined the self-empowerment of The Escorts with the scare-straight tactics of the original Lifers Group. According to the credits, 7 rappers were featured on both releases: Amazing G #212238, Original #219625, Aleem #207015, Almighty L #209021, Knowledge Born Allah #210748, B-Wise #200662 and Rocky D #200394. More were listed, and even more participated without being credited. Not all of them were equally accomplished rappers, but given the circumstances these songs were recorded under, the quality is actually considerable. The often hectic, early ’90s beats provided by the production team of Dr. Jam, Madness 4 Real and Phase 5 (who also cut tracks for MC Ren, Eazy-E, Ice Cube, WC, Mack 10 and Da Lench Mob) helped override potential insecurities in the delivery.

With so many contributors it would be illusory to expect a streamlined message. Even though a vocal ensemble cantillates “Please give us another chance” at the end of “Let Me Out,” there’s no such thing as a rap version of “All We Need (Is Another Chance),” on which The Escorts assured the audience that “We mean truly what we say” and pleaded, “All we need is another chance, please give it to us.” “Let Me Out” comes the closest to “All We Need” with one convict offering, “I’m 25 and I spent half my life inside a prison,” another vowing, “Prison ain’t nothin’ but mental slavery / but I’m strong, I don’t let this shit faze me,” and another warning, “Don’t come to jail cause in jail you won’t have no clout / Bein’ a gangsta? That’s not what it’s all about.” But there’s also the guy who poses as “Satan in a jail, trapped, mad as hell,” boasting:

“I shot a nigga, now that muthafucka’s comatose

It’s his girl fault, the bitch shouldn’ta played me close

I can’t help it if I’m lookin’ like a million bucks

I’m in the club and your girl comes up and wants to fuck

You understand me… capisc?

You shoulda kept the horny bitch on a leash

Now society is steady tryin’ me

I did it and I’ll do it again, I ain’t lyin’, gee

[…]

I swear to God, they better try to chain my soul

these muthafuckas better never let me make parole”

If that rapper would be taken serious, I doubt any parole board would give him another chance. And if they didn’t take him serious, why should his target audience – kids – take him serious? And therein lies the dilemma of “Living Proof” and many other well-intentioned projects. How do you create a rap album that credibly depicts street and prison life without any glorification whatsoever when the main attraction of many rap albums is that they credibly depict street and prison life? In other words, how many kids have been scared straight by a rap album? How many rap albums have warned of the pitfalls of a criminal lifestyle without sounding preachy? Fact is, it takes a KRS-One to author a convincing cautionary tale (“Love’s Gonna Get’Cha (Material Love)”). It’s just that MC’s the caliber of KRS-One are rarely confined to a prison cell. And that even they can’t avoid coming across preachy most of the time.

What the Lifers had going for them wass the fact that they’ve undoubtedly walked the walk. As their debut single stated, they were “The Real Deal.” They had credibility. They had authority. That’s why Knowledge Born Allah had no problem calling out big rap stars: “You never been to prison, you never seen one / Fuck N.W.A! Put down your watergun.” Regardless of whether “Living Proof” had the intended effect, the Lifers had a lot of interesting things to say. Many of them thought it all began when they were young (“Hardcore, ruthless, rough, rugged and wild / that’s the way I been ever since I was a child”), to the point even where they felt they were doomed from the start (“As a baby my ribbon was stamped ‘Go to prison'”). They dissected the psychology of the judicial system (“They let you get out, they fill you with doubt / so you can come back, yeah, that’s what it’s about”). They struggled to keep their sanity (“I seen death pass my eyes before / but I see it more often when I walk down the corridor / of the state pen behind the prison walls / but it won’t break me down, I must stand tall”). They discussed the social causes of crime (“They say I did a crime, I say that I am a outlaw / I am not a criminal, I did it cause I’m dirt-poor”). They lamented the loss of their social status (“They took my silk suits, gave me khakis and jail boots / it hurts me to my heart to be broke with no loot”). They pondered their career in showbiz (“Many people say Knowledge is a rap star / well I’m not, I’m just a inmate behind bars”). And they made it clear that all of this is very real to them (“You get no breaks, this ain’t no Broadway / day for day you’ll do your time up in Rahway”).

The Lifers pointed out that they were not out to glorify criminal behavior. But where does depiction end and glorification start? Which advice is best heeded by an age group that seems to be particularly resistant to advice? What if youngsters are so alienated by society they begin to view the company of criminals as a community that will accept them? What if warnings are perceived as a challenge to prove one’s manhood? Whatever the case, songs like “Rise Or Fall,” “Out of Sight, Out of Mind” and “Short Life of a Gangsta” (also included as a remix by labelmates Organized Konfusion) did their best to caution kids and not make prison seem like the place to be. “Each one teach one – how many have reached one?” Knowledge asks on “Prison Is the Death of a Poor Man,” and there is no doubt that with “Living Proof” the Lifers Group did more to reach kids than many professional rappers during their entire career.

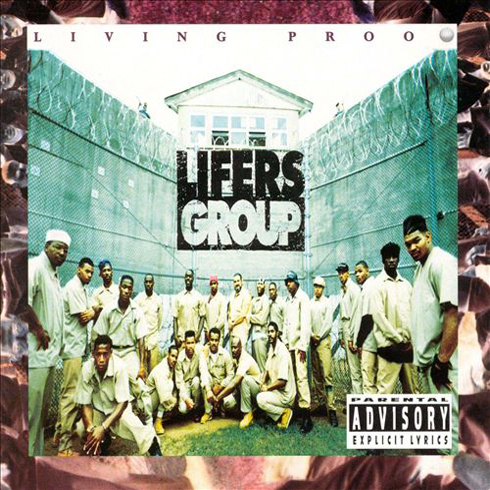

“I’m not tryin’ to scare you, believe it or not / you’ll believe what I’m sayin’ when that ass get got,” one Lifer says on the title track. Which indicates that the rap act Lifers Group was not bent on scaring potential juvenile offenders straight. Rather, it was a specific attempt to reach the rap generation with the basic philosophy that had been pursued at Rahway since the early ’70s. To get convicted felons involved in crime prevention. Looking at the personel listed in the credits of this CD, from all the inmates, the members of the Lifers rap group and those of Lifers Group Inc. (22 men pose for the front cover), to musicians that were also inmates, to Prince Paul and Yo! MTV Raps’ Doctor Dré providing scratches, it’s obvious that everyone involved realized that this was much more than a rap novelty act. With apparently little intervention from the authorities, “Living Proof” gives it to you raw, just like rap music had done since the ’80s.

The n word is frequently used, as are other terms and descriptions that would have been completely unthinkable on a record 20 years earlier. The album does contain singing, but clearly behind bars as well rap had taken over from rhythm and blues. But you’d have to be deaf not to hear the direct relation between the Lifers Group and The Escorts, whose first album “All We Need Is Another Chance” contained soundbites that were sampled by several rap acts, most notably Public Enemy on the seminal “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back.” But as John Ridley observed in the liner notes to “Prisoners of Soul”: ‘The Escorts’ type of soul is sadly no longer in the mainstream of the urban market. The songs on this CD were cut at a time when soul groups were at the height of their popularity, and for the Escorts to have made their mark in a very crowded arena speaks volumes for the high class of their output. You can still hear this quality quite clearly some 25 years later. They may have been prisoners in the flesh but their souls were free.’

Similarly touching words are harder to find when it comes to the Lifers Group. But touching moments are found in abundance on this album – the urgency of the hook to “One Life to Live,” the Doctor Dré-conducted old school festivity “Freestyle 1”, the frustration and bitterness contained within “Cuff ‘Em Up,” the inclusion of table-drumming in the bluesy title song, the funk excursion “Emotional Violence,” the professional hardcore rap that is “Back in the Days.” “Living Proof” is a truly unique rap album even if it’s not always that apparent. When it came to keeping it real, it probably didn’t get any realer than this non-profit organization, and that should have been reason enough to listen what these guys have to say:

“I’m speakin’ from the first person point of view

Thoughts are conversed to let you know what I go through

Givin’ food for thought to feed the mind

Stimulate the brain with each punchline

I entered the system with a mind healthy and sane

Now I got nothin’ to lose and everything to gain”