If you run a rap music-related search, you may happen to come across a loose collection of webpages that meticulously list comments found on rap records that can be interpreted as expressing racism towards whites. Many of them contain the term ‘devil’ as coined by radical black supremacist Elijah Muhammad. Some of these quotations are thoroughly racist, and seeing them bundled together did have a somewhat sobering effect on me when I first stumbled upon the site years ago, even though it does little to conceal its own agenda, citing as its purpose: ‘Black and Latin musicians issue forth violent racism and the target of their hatred is primarily whites. The web pages that follow expose some of the lyrics. The exposure is necessary because civil rights groups do little to bring attention to the violent racism of rap, left-wing rock, or raggae [sic], and instead civil rights groups focus on violent racism of right-wing rock issued forth by white musicians.’

As a white rap fan who got wise in the late ’80s and early ’90s, I learned that pro-black doesn’t automatically mean anti-white. Still I was open to rap lyrics that suggested that with my skin color, I was part of a problem. How could I not be perceptive of such a notion? You’re a kid playing cowboys and Indians, and as you read up on Native Americans, you realize what a miserable card they were dealt. You go to school, hear about colonization and slavery, and you come of age witnessing the last years of South Africa’s apalling Apartheid regime. It was inevitable that I would develop that vague feeling called white guilt. The feeling is gone, but even today I am much more offended by white racism because I feel it comes from a position of power, while I am liable to excuse black racism as a reaction to past and present discrimination. Call it hipocrisy, I call it looking at things from a historical perspective.

So there I was, a young white teenager attentively listening to these rappers as they spread their pro-black and sometimes anti-white message. I knew that I didn’t belong to their target audience, but I also felt that it would be wrong to take that as an excuse to ignore what was being said. For every rap fan – even one as unlikely as me – there comes a time when he has to ask himself: Are they talking about me? When you get into rap music, you learn not to take it too personal. Rappers have a habit of pointing the finger at people, and you learn quickly not to feel affected by their accusations, even if they might in fact be talking about you. Usually they’re not. But sometimes they are. Sometimes rap IS personal. If it weren’t, we wouldn’t get so attached to it. In regards to us white fans, it’s only right that we feel a little bit uncomfortable every now and then. Too often we stand on the sidelines, silent spectators to the good and the bad things happening in hip-hop.

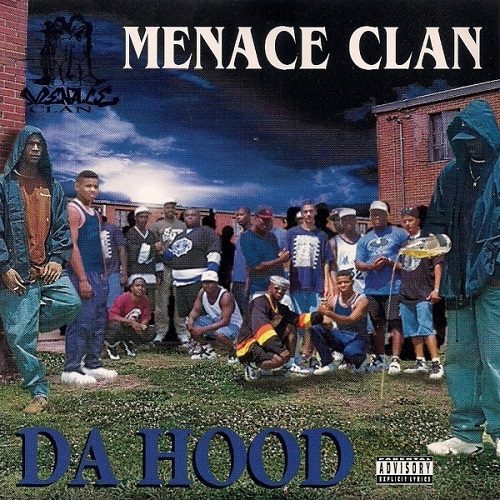

Pathetically put, if I truly love this rap shit, it’s not enough to have songs that make me feel welcome, there also have to be the ones that hurt my feelings. Someone, something has to make me feel unwanted, giving me reason to fight for it, to re-establish my relationship with rap. That is the reason I set out to dig deep into my collection to find the ultimate rap record to test how thick that white skin of mine is. Well, Menace Clan’s “Da Hood” might just fit the bill. To say it with Brad Jordan: “You brought to us the KKK, we bring to you the Menace Clan.”

Some Ku-Klux Klan official makes a brief appearance at the top of the album in an interview segment, but the Menace Clan cuts him short and makes sure to have the last word. It begins with “Rappers say they black but I’m blacker / I take a Tec-9 and kill a muthafuckin’ cracker,” and continues along those lines for the remainder of the album. There have been many complaints about the ways of the music business, but none took it as far as “Record Deal,” which suggests that rappers “grab that devil in a choke-hold” “just before you lay them vocals.” We’ll assume that the South Central LA duo had some disheartening experiences prior to signing with Rap-A-Lot Records. Why else would they boast, “I don’t give a fuck if the record label drop me / I don’t give a fuck if I sell one copy”? Then again, any obstacles they faced really shouldn’t have come as a surprise given their admission “I can’t get no deal cause I say ‘Fuck white people’.” On the other hand, they certainly had a point when they argued, “I could get a record deal if I just said ‘Fuck niggas’.”

To the duo’s credit, they don’t spend the entire album inciting hate crimes. They accurately relay the making of a “Mad Nigga,” narrating his short life from start to finish, from the crack baby born to neglecting parents, to the juvenile delinquent’s early death. After praying “to God for help” and admitting, “My niggas and myself […] we need some mental health,” Dee and Assassin tap into their own anger as they “remember 4/29/1992.” This date puts “Da Hood” in a context that makes its contempt a little bit easier to categorize. Big Jess, who assisted KAM and MC Ren on their post-LA Riots/Rebellion efforts, produces the opening “Aggravated Mayheim” and the closing “Kill Whitey,” which may both be more immediate reactions to the Rodney King verdict than the album’s 1995 release date suggests.

Although it does have its artistic merits, “Da Hood” is ultimately short-stopped by its simplistic message. Demonizing white people as devils, citing synonyms that can again be traced back to Elijah Muhammad (“The white man is a devil, a beast, bezerk, snake, Satan, serpent, evil, wicked, dragon, demonic, hell-born, vicious, Iblis, savage, brutal, wild, fierce, untamed, the archenemy, father of lies, prince of darkness”) is the very opposite of making a clever case against any white power structure as it might exist. “Kill Whitey” could pass as a call for unity amongst gangs, Assassin referring to Crips and Bloods as soldiers he’s “recruitin'” in hopes they get to “drive-by shootin’ on this white genetic mutant,” but there is so little conviction behind the argument, it is easily contradicted by the gangbanging “Last Driveby.” Then there’s an interlude where one of them specifies, “We only trippin’ on the white muthafuckas that’s in control of the government […] we ain’t trippin’ on you common folk crackers cause y’all just crackers […] y’all might as well be niggas.” Incidentally, they recall another anti-government figure when Dee argues, “Because these crackers yell ‘nigger’ I show them I got no pity / I’m one of them terroristic niggas bombin’ Oklahoma City.” The only thing is, Timothy McVeigh was white. Or does the fact that he was opposing those “in control of the government” make him a “common folk cracker” who might as well be a “nigga”?

Those abiding by a strict moral code are likely to be apalled by any attempt to justify racism. They may be right. But the world isn’t black and white, as much as George W. Bush would like it to be, as much as the Menace Clan would have liked it to be. “Da Hood” offers no lengthy explanations for its rampant racism. But a key track in ‘understanding’ the Menace Clan is “Runaway Slave,” which sends the two rappers on a dramatic escape from the plantation. The rest of the album was closer to Dante Miller and Walter Adams’ everyday situation. They call life the “ultimate drive-by” (“…you can duck and dive, run and hide, but everybody gon’ die”). They profess their dedication to the neighborhood they “die for, lie for, cry for, ride for” (“…the only reason that I come outside for”).

It wasn’t all good in Menace Clan’s hood – “My hood’s a pen and all my people’s inmates,” says Dee on the Bushwick Bill-assisted title track. There’s nobody to trust (“Me By Myself”), the climate is so cold packing heat becomes mandatory (“Cold World”), and bullets play such an important role that they’ve been assigned a lead part in “Da Bullet.” The album hits its creative peak on “What You Say,” a dispute between Dee and an elder man (played by his partner in rhyme) who tells them that they’re “a disgrace to the whole black race.” The generation gap opens wide when he remembers, “I used to march with Martin Luther King,” and Dee responds, “What you gon’ do when / Armageddon sets in and the feds start shootin’? / You gon’ be marchin’ while my khakis stay starched, and / Martin wasn’t shootin’, that’s why Martin ain’t marchin’.”

Largely produced by Rap-A-Lot in-house producers, “Da Hood” is an album that from a strictly musical viewpoint does many things right. It goes, however, terribly wrong when it comes to the message. Racist rhetoric is intolerable, no matter how thick-skinned one might be. Using it means making a deal with the REAL devil. And you know how that one usually turns out. The Menace Clan let themselves be blinded by hatred and while trying to beat ’em, almost join ’em.