Rap music’s path is littered with unreleased albums that fell by the wayside because someone behind a desk decided it would be better not to release them. Some of the more famous ones have long been available as vinyl bootlegs (Large Professor’s “The LP” comes to mind), but it takes a truly dedicated artist to pursue a proper release years after the fact (Cormega and “The Testament” being the most notorious example). Lesser known artists are more liable to insist on a release, some of them even seizing the opportunity to rise to late prominence (Dooley-O with “Watch My Moves 1990”). Whatever the exact circumstances, the fact that people are willing to resurrect music that was once deemed doomed shows that there are plenty of heads who feel nostalgic about the kind of music they listened to when they were younger or who are interested in catching up on artists that came before their time. Still, crate-digging as a commerce is rarely a top priority to anyone.

After “Power of the Dollar” was shelved, 50 Cent decided to take his hustle back to the streets, which he did so successfully that the tables eventually turned and he was in a position to negotiate contracts at his terms. It’s unlikely that he will bother to put out material that has already been heavily bootlegged or used during his mixtape days. The same goes for Twista’s sophomore effort “Da Resurrection” and whatever the Black Eyed Peas recorded when they were known as the Atban Klann and signed to Ruthless Records. Most likely it’s indie cats making sure their work is saved from oblivion. J-Live did it with “The Best Part.” Del did it with “Future Development.” Blood of Abraham did it with “Eyedollartree.” Pete Rock did it with INI’s “Center of Attention.” DOOM did it with KMD’s “Black Bastards.” On the other hand, sometimes material marinates a few years before it is used under a different title (parts of Lady of Rage’s “Necessary Roughness” would probably have been on “Eargasms”). Finally, in more recent times there have been semi-official releases of unknown origin (such as King Tee’s “Thy Kingdom Come”).

One particularly personal belated first edition was the “Big Shots” album Peanut Butter Wolf put out in memory of his deceased partner Charizma. There are other aborted albums that probably only this reviewer would care about. Mid-’90s follow-ups by Shazzy (“Ghettosburg Address”) and Pudgee Tha Fat Bastard (“King of New York”). The Omniscence album. The Fatal album. And there are the ones that should stay in the closet, like Freddie Foxxx’s “Crazy Like a Foxxx.” But there remain some rather special albums that need to see the light of day in their entirety and officially. The 1993 full-length the Jungle Brothers recorded for Warner, “Crazy Wisdom Masters” (which was incompletely transferred to “J Beez Wit the Remedy”). “Night of the Bloody Apes,” the 1994 Jive album by the Crustified Dibbs (RA the Rugged Man’s outfit). The Prince Paul-produced Resident Alien album “It Takes a Nation of Suckers to Let Us In” from 1991. Ras Kass’ more recent “Van Gogh.” Q-Tip’s Kamal the Abstract material. Whatever Rakim recorded for Aftermath. Black Thought’s “Masterpiece Theatre.” The original version of Nas’ “I Am.”

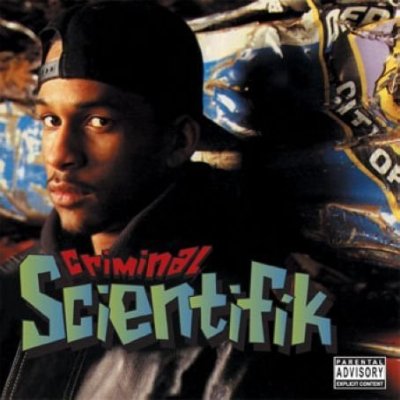

Yet another story is Scientifik’s “Criminal.” Scheduled for release in 1994, this album never reached the stores because its label, Definite Records, went out of business after the release of the single “Jungles of da East b/w Lawtown.” The record has been available on wax packaged in a plain sleeve, but in 2006 Traffic Entertainment gives it the official release it deserves. Sadly, Scientifik isn’t around to witness it, as he died in 1998 in a car accident that followed a shooting inside the car, investigators at the time suspecting he first shot the woman who was with him and then turned the gun on himself, but also admitting that the couple’s background didn’t suggest such a horrible scenario. Scientifik (moving from Brooklyn to Lawrence, MA, at the age of 12 after his mother had died) had been active on the Boston rap scene, producing demo tracks with Joe Mansfield (who contributed beats to Ed O.G’s debut “Life of a Kid in the Ghetto”) in the early ’90s while still being a teenager.

One reason people wouldn’t forget about “Criminal” was the production. Not only do Buckwild (3 tracks) and Diamond D (2 tracks) make this almost a DITC affair, one beat was even done by The RZA. In all likeliness it all began with Diamond being involved in Ed O.G’s 1993 album “Roxbury 02119,” and him bringing in Buck, who had been down with Diggin’ In The Crates for some time. Initially, Scientifik might have even been labelmates with Edo, as their collaboration “As Long As You Know” was included on the former’s “Love Comes and Goes” single, as a means to promote (quoted from the credits) ‘Scientifik’s debut Chemistry/Mercury CD and cassette “Prestige, Image, Money & Power”.’ Which, it is safe to assume, would become (the not particularly appropriately titled) “Criminal.”

In terms of its content, “Criminal” is far from the reckless manifestation of a criminal mind one might expect. Rather, the rapper shows that what the law calls a crime can be much more complex: “This nigga tried to get me but he missed when his tool bust / some niggas carjacked his little sister’s school bus / ain’t hit no wools but was trippin’ on meth / when nigga cocked the hammer back and put the gun to his own chest.” While delivering a first person account on the title track, Scientifik reflects on urban mysery in general, concluding, “They probably find a cure for cancer ‘fore they handle the streets.”

Furthermore, “Still An Herb Dealer” isn’t exactly the confession of a stone-cold crook, the rather harmless revelation setting him apart from today’s part-time rappers/full-time trappers (to use Yo Gotti’s terminology). There’s some unlawful activity in “Lawtown,” but again it’s primarily Scientifik’s way to illustrate the code of the streets:

“Hey yo Jack, quit the bullshit, it’s a stick-up

Every single day this nigga drop off or pick up

mad loot in the Jeep; I don’t sleep on that bastard

cause I got his route mastered

He and his people run shit like a track meet

They be hittin’ backstreets in they black Jeep

with the fat beat boomin’ out the box

but he always turn it down when he transportin’ rocks

Been on the block for a minute

The spot’s gettin’ money in it

and I ain’t gettin’ a percentage

I feel misrepresented in my own territory

He never saw me when niggas broke into the door; we

hemmed him up and took him straight to the back

pistol-whipped him with gats till he handed the stack

Told him that he shouldn’t even fuck around like that

In Lawtown it goes down like that”

While he didn’t stray from standard subject matter, Scientifik was able to pepper his observations with humour, for instance on “Overnite Gangsta” and “Downlo Ho,” which are both entertaining despite their tired topics. Example:

“The other day I seen you troopin’ around the way

frontin’ hard cause you was bumpin’ shit by Dr. Dre

Well, you could bump Ice Cube, Geto Boys and Ren

You’d still get your ass smacked like back then”

Speaking of, the aforementioned “Jungles of da East” carries a slight West Coast resentment. Sampling Jeru’s anti-gangsta rap anthem “Come Clean,” “Jungles of da East” is less confrontational but does contain some clues that Scientifik was uneasy with how by 1994 the west had paralleled the east in terms of success. He raps, “1994 is all about the East Coast / Thought the other shit was raw? Well, it didn’t get close / to the niggas from Brooklyn, Philly to the Bury.” He goes on to mention various states and spots, giving a rather broad definition of the term East Coast by including even Atlanta and Florida. Intending to “throw the ball back” Sci bigs up “the East Coast, cause I never hear enough of that shit / and I be damned cause we the ones who got the fat shit.”

Truth be told, he makes a stronger case on “Fallen Star,” where he boldly disses rap stars whose time is up, comparing himself to a young KRS-One taking on Melle Mel and generally renouncing fame:

“Since I don’t live in the sky don’t classify me as a star

Now I don’t give a fuck if a sucker duck was platinum

He won’t be livin’ fat with a bullet from a gat in him

You just another sucker starin’ hard, bitch

Fuck around and try to step and catch a scar stitch

[…]

You’ll never find another brother truer to the game

so you’ll never see my name on no fuckin’ walk of fame”

Whether he wanted to be one or not, Scientifik was denied the chance to become a star, while producers like RZA, Buckwild and Diamond D garnered enough star power to unearth a hip-hop album they happened to be a part of sometime in ’93 or ’94. Assisted by DJ Nestle Quick on the wheels of steel, the producers all adhere to the slow tempo that had East Coast rap in its spell by the mid-’90s. It’s a very dark brand of jeep beats, dominated by the bass/beat structure, with the buzzing bass often acting as the major melodic element. RZA’s “As Long As You Know” is in the vein of his more traditional work for N-Tyce from around the same time. Rhythm Nigga Joe (Mansfield) (“Still An Herb Dealer”) and DJ Shame (“Jungles of da East”) would become known as the Vinyl Re-Animators. And Buckwild and Diamond D both put in pure quality work, but get kind of outshined by Edo.G, who beats DITC at their own game with the sinister “Lawtown” (where after-midnight jazz sparkles meet dry, hard-hitting drums) and the creepy, Nas-sampling “Criminal.”

“Finally a MC you can trust in,” Scientifik introduced himself on this would-be-debut. While he possessed the laid-back demeanor of a vet, the thought and energy put into the lyrics and vocals betray the young buck excited to be rhyming: “It’s the start-beef shit / on-the-creep shit / real deep shit / not the weak shit / peep shit as I freak shit / on some old yo-you-better-not-sleep shit / I take ya out like that clean version beep shit.” Switching between wordplay, verbal gunplay and common sense commentary, Sci presented himself as an ambitious, aspiring rapper who had only just begun (“I Got Planz”). His diction wasn’t always the clearest, his flow sometimes too reminiscent of his mentor Edo, but this finally released album reveals an independently-minded MC who would always try to argue before resorting to criminal behavior. “Criminal” may not be nearly as flawless, but ten tracks deep and boasting a cast of producers that was only a few notches below dream team status, it comes very close to an underground version of “Illmatic.”