Hip-Hop history the way I was taught it draws a clear dividing line between old school and new school, with Run-D.M.C.’s “Sucker MC’s” getting singled out as the song that changed it all. Once you take a closer look at the decade in question, however, the situation is less clear with several artists having direct ties to the old school without having the distinction of being absolute pioneers. Were artists such as Whodini, UTFO, Doug E. Fresh, The Boogie Boys, T La Rock or the Fat Boys old or new school? Not to mention those who started out in the earlier, but whose career wouldn’t take off until the later ’80s, like say, Ice-T.

A by any means exceptional case was Donald-D, who in fact for a while was closely associated with Ice-T. According to his own account, the Bronx-born and -bread b-boy got into the musical side of it as one half of the As Salaam Brothers which he formed with Easy AD of the Cold Crush Brothers, and as a member of The Funk Machine, an outfit lead by Afrika Islam, Son of Bambaataa. Between 1983 and 1985 Dee was the MC on the latter’s Zulu Beat radio show on WHBI, the station that hosted Mr. Magic’s pioneering format. Zulu Beat, broadcast on Wednesdays from 1-3 PM, according to the UK’s P Brothers (who some years ago released a tribute mix), ‘was the first to mix a true hip-hop selection of electro, soul, funk, reggae and a heavy dose of breakbeats,’ its circulating tapings being ‘important in relaying the true musical blueprint of hip-hop beyond the few imported electro records that were available to buy in England at the time. More than anything else, tapes of the Zulu Beat show introduced a lot of people outside of the USA to the importance of breakbeats, and they also showed that a hip-hop DJ selection is made up of different musical styles beyond just rap records. Copies of the show tapes travelled and so also helped spread the word of the mighty Universal Zulu Nation and the knowledge and science of hip-hop that goes beyond the music itself.’ (Quoted from the P Brothers’ “Zulu Beat” CD liner notes.)

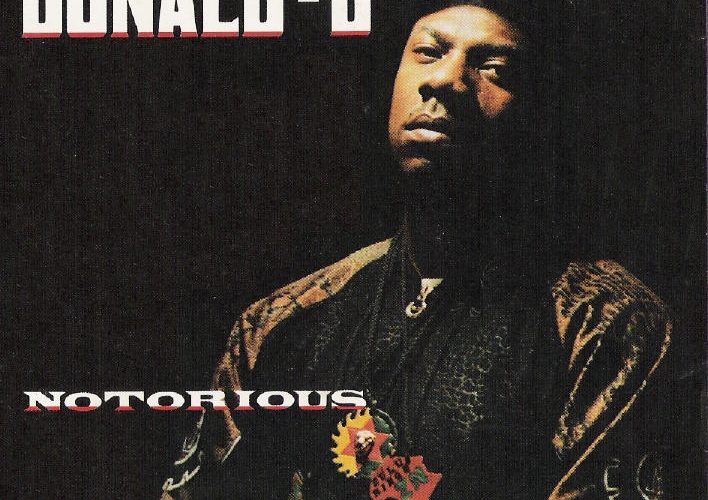

Besides releasing the Grandmaster Flash-produced “Don’s Groove” on Elektra in ’84, Donald-D also teamed up with DJ Chuck Chillout under the moniker The B-Boys, recording “Rock the House” in ’83 and, after Chillout left, two more singles with Brother-B and DJ Master T, “Stick Up Kid” b/w “Girls” and “Girls Part 2” in ’85. The self-appointed Microphone King released another solo single in ’87, “Dope Jam” b/w “Outlaw,” before leaving New York for Los Angeles to join Ice-T’s Rhyme Syndicate, where Afrika Islam had also found a new home. He debuted out west on the compilation “Rhyme Syndicate Comin’ Through” and was the first Syndicate rhymer after Ice-T to put out a full-length, 1989’s “Notorious.”

Unlike many other later ’80s rap acts who had experienced the hip-hop earthquake at a certain distance from its epicenter, Donald-D had been right there in the middle of it. For an original Zulu King to leave New York and finally get his career in full gear in Los Angeles is an extraordinary event in hip-hop history. In a fast-paced era where MC’s would sign off with “I’m outta here like last year,” “Notorious” reflects that unique constellation, Donald-D presenting himself as a contemporary MC who at the same time is fully aware of what brought him here.

Boasting one of the most memorable intros of all time, “Notorious” opens with an operator announcing, “This is a test of the emergency broadcast system,” before an assortment of sirens, “Bring the Noise” samples, cuts and stabs, supported by a rolling piano sampled in the background, kick in. On top of it, vocals introduce “Donald-D, notorious rhymer” and “Syndicate Sniper.” It’s the type of musical wake-up call that to me for the longest epitomized hardcore hip-hop. The following title track is an understated mixture of slick, sparse drums, a not particularly distinct but still dominant bassline and samples – “A Funky Song” and “Soul Vibrations” – that only seemingly denominate the musical direction the album will take. Because while it reflects the free-for-all spirit prior to sampling prosecution, the organized chaos of late ’80s hip-hop is in full effect here, with often densely packed tracks, forcing their way with the energy of a twister, sampled bits and pieces and cuts and scratches spiraling and swirling around, contained by an unseen force. The optimism of soul, the freakiness of funk and the languor of blues were being replaced by the urgency of hip-hop, hard-edged, hammering, hotly contested.

Referring to a decade of experience, Dee quipped, “I ain’t no rookie lookin’ for a chance.” He promoted himself as “the best pound for pound” and as being “platinum-bound,” only reluctantly giving up props: “You heard the R go off, LL show off / and many other rappers to Dee are marshmellow-soft.” Knowing that he re-entered a crowded market, Don offered: “Nowadays for rap you crave / too many amateurs are playin’ the stage / givin’ rap a bad rap because they can’t rap / studio rappers, play the back / and witness the fitness while I flaunt the gift / you wanna battle, I ain’t the one to try to get with.”

Lyrically, this opening salvo sometimes borders on being old fashioned. You would have hardly heard Rakim, MC Shan, KRS-One or Chuck D say about themselves “The General Custer of rap ain’t lackluster.” Yet there’s something timeless about this theme song. A particular air surrounds Donald-D that establishes a natural authority that many rappers lack. You couldn’t call it menacing, but there’s a slight gangster touch to his presence, on a lyrical level reinforced by the assertion that “rap ain’t some kiddie game.” Like behind the word ‘notorious,’ there was a certain mystique behind Donald-D’s cold, clear tenor. When he said, “I’m the grim reaper of rap,” you weren’t ready to right away dismiss it as yet another lame analogy.

Obviously, these days ‘gangster’ is about as shallow a term as any in the rap vernacular. Dee himself steers clear from any such cliché on “Notorious,” apart from the thinly veiled warning of the album title. One cut has him even wondering, “I’m no criminal, why am I treated like one / yo, what have I done?” “Who Got the Gun” – set to the same booming sample Diamond D would later use for “I’m Outta Here” – is a mystery tale involving false accusations, police brutality, kidnapping, corrupt cops, shoot-outs, and a missing gun which serves as a compelling story arc. The listener rides shotgun, remaining just as ignorant as the hero, who, continuously asked about some gun, begins to wonder himself where this mystery weapon is:

“Chained against the wall like a wild beast

This smelled like the dirt of police

They said: ‘Give up the gun’ – I don’t heed it

Mistaken identity was how I pleaded

They questioned my whereabouts on the 5th of June

When a cop entered the room

He said: ‘Fuck it, put a bullet through the nigger’

Out of this hell hole I had to figure

The bossman told ’em to chill on the kill

He said: ‘Listen, we will front you a deal

You can keep the money, here’s a kilo for fun

but all you gotta do is get us the gun’

They stepped off, so I tried to relax

but felt uneasy by the sound of rats

piecin’ away on the wooden door

This is a long way from bein’ on tour

Too strong to weap, won’t sell myself cheap

Slowly but surely I was fallin’ asleep

with a thought on my mind that continued to run

I would like to know – who got the gun?”

“Car Chase” is a breathless account of a bank robbery and ensuing escape, a Bonnie & Clyde tale with a happy ending, the musical suspense being provided by a Pleasure break (“Joyous”). “On Tour” lacks the humor of Ice-T’s later “Lifestyles of the Rich and Infamous” but is a testament to Dee’s calling as a performer, as he confirms, “I was born to be on tour,” quotes his own routines from yesteryear (from “Dope Jam”) and shares the spotlight with his DJ Chilly-D. Then there’s the closing “Another Night in the Bronx,” a who’s who of old school rap where Dee bumps into just about everybody who ever emceed or deejayed in the Bronx, beginning with a routinely witnessed murder and ending with another encounter with law enforcement:

“Gunshot blast – what was his last words?

Damn, everybody in the neighborhood heard

gunshots ringin’ out in the PM

And when we saw him, nobody knew him

Was he a drug dealer? Who would be the squealer?

I wonder if the brother knew his killer

As the cops stepped in, the posse cold stepped

This was another night in the B-R-O-N-X

(…)

I’m cruisin’ the town in my Audi

Cops pull me over cause they say I’m rowdy

Searchin’ me down, do you know what they found?

A real rap trooper from the Boogie Down

that travels the airwaves to everybody borough

Donald-D, y’all, is a devastating thorough-

bred makin’ bread, puttin’ heads to bed

I’m Nikin’, you’re bikin’ in played out Pro-Keds

Instead the feds are playin’ me close

cause I’m the Syndicate Sniper that they want the most”

All of this is highly interesting, but almost overshadowed by “F.B.I.” The album’s single, “F.B.I.” took a long look at the crack problem from all possible angles, Dee giving examples of the exceptionally cheap, addictive and hazardous substance turning women into whores, of neglected children, of the drug dealer issuing his standard justification, of “sport figures” who “didn’t show for the game / because of the pipe and flame,” of “the rich and famous” who “will try to blame this / on the people from the street / so they can keep / out of the media, but they can’t sweep / it under the rug / they caught the drug bug / and their own grave has been dug.” There’s nothing glorifying about this track, from the urgent caution in the intro, to the five verses dealing with the various actors in the crack game. Check take 2:

“She’s out of control on the AM stroll

24-7 her body is sold

She used to be the neighborhood fly girl

but now the base pipe has entered her world

I saw her one night in a alley slobbin’ the knob

To her it’s a full-time job

The sucker with her was lookin’ for cheap sex

For 50 cents she said I could be next

So I snatched the bitch by her nappy weave

and I said: ‘Girlfriend please

You better check into a rehabilitation

cause you’re a fuckin’ crack patient!’

The bitch dissed me, swung and missed me

then she asked, could she kiss me

It was the crack on full attack

that had this beautiful sister trapped”

Even within the so-called Golden Era, “F.B.I.” is an exceptional song. Rapping with drive and determination, Donald-D assumes the position of a modern age town crier, as the uptempo beat’s bleeps and breaks illustrate the social devastation described in the lyrics. But the most chilling part is the barely coded message of the song’s title and its loudly chanted hook “At the F.B.I. / Free-Base Institute / That’s where they go to get high!”

“F.B.I.” was the one song that made this album notorious not just in name. It remains the centerpiece of Donald-D’s discography. Apart from that, “Notorious” had few political undertones. The strictly metaphorically titled “Armed and Dangerous” calls for a “nation in unity with peace and harmony” and promotes freedom of speech similarly to Ice-T that same year. It also was one of those ’80s tracks where rap built self-esteem:

“They say it’s street sound

but check Billboard, rap holds its ground

outsellin’ some of music’s biggest stars

but rap gets treated like it come from Mars

The stereotypin’ BS has got to stop

We’re no crooks, so don’t play cop

I see my sisters and brothers gettin’ hip to the game

while some sell out for the price of fame

That’s why I praise Public Enemy and BDP

and my homeboy Ice-T

They preach black awareness, they kick the knowledge

that should be taught in college

and in grade school; shouldn’t be a mystery

teachin’ blacks about black history”

Not to question Donald’s artistic independency, but two songs should probably be attributed to (opposing) outside influences. “A Letter I’ll Never Send” may be too elaborate to be a hit love song, but it still sticks out with its breezy guitar-strumming and sentimental intonation. It wouldn’t be a surprise to find out the major insisted on its inclusion. At the other end of the spectrum is “Just Suck,” which can be seen as the album’s concession to an Ice-T pet peeve (it is even introduced as being in the vein of “Sex” and “L.G.B.N.A.F.”) Over an aggressive assortment of drums and stabs, Dee gets more explicit than any other rapper before outside of Miami (Ice included). It’s the prototype of a boastful sex joint, a premonition to all the guys that they’re gonna see their girlfriends turn into groupies when the Syndicate hits their city. Only partially tempered by humor, “Just Suck” is very graphic (including a female voice in a ‘supporting role’) and even after all these years of sexually explicit rap music borderline tasteless. Last but not least, it clearly served as an inspiration for N.W.A’s “Just Don’t Bite It.”

Both “A Letter I’ll Never Send” and “Just Suck” feel out of place on “Notorious,” and not just because they express opposite moods. Making up for it, Ice and Dee manage to capture a true hip-hop moment with “Lost in a Freestyle,” where they pass the mic for five minutes straight over a funky “You Can Have Your Watergate” loop, realizing that they literally got lost in a freestyle.

All told, “Notorious” works because beats and rhymes form a unity. None of the combinations are arbitrary, the music always reflecting the message of the song. Just once, on “A Letter I’ll Never Send,” Dee overacts. Him and Afrika Islam are credited with production, but if I understand the term ‘programming’ correctly, the tracks were put together by Islam, with Johnny Rivers programming “A Letter I’ll Never Send” und “On Tour” and DJ Chilly-D “Lost in a Freestyle” and “Another Night in the Bronx.” Chilly-D had been Donald’s DJ at least since the “Dope Jam” days and he gets busy throughout “Notorious” (DJ Aladdin is also mentioned). A remastered version would unquestionably sound better, as I’ve been forced to bump the signal (i.e. turn up the volume) considerably during this review. That aside, “Notorious” is a very solid (and often forgotten) example of why rap ruled in 1989.

On “Outlaw,” Donald had said about himself and DJ Chilly-D, “We’re real rap stars while others are actors.” On “Notorious” their “Outlaw” remake was called “Syndicate Posse,” a faster and more furious version that mirrors the change in pace and sound that took place in that crucial period from 1987-1989. It probably wasn’t until they started rolling with the Syndicate that the duo would finally ascend to “real rap stars.” With the dawning of the ’90s, Donald-D’s career would take yet another turn, but with “Notorious,” he had his place in history as a rapper who left his mark in different times already secured.