Blues, rock ‘n roll, rhythm & blues, gospel, soul, jazz, funk – in many ways hip-hop and rap are a chip off these old blocks. Several of rap music’s characteristics can be traced directly back to these influences. If hip-hop producers sample old records, it’s not just because it can be a cheap and easy way to create a musical theme, it’s also because that was the music they grew up with until a certain age. But there comes a time in every teenager’s life when he takes control over his own turntable/tape deck/CD player/computer and makes his own musical choices. That’s when young people start to listen to their own generation’s music, or more specifically the music their older siblings make. During its formative years, certain aspects about rap music were liable to cause division between the rap kids and their more mature relatives, most notably the use of street language, the absence of singing and the unabashed incorporation of existing compositions. But in reality the generation gap may not have been as wide.

The strongest case for its firmly rooted existence rap always made itself, and with sampling still being an option, an ever-growing number of – adequately compensated – musicians continue to benefit from hip-hop’s strong embrace. As Stetsasonic once put it: “Tell the truth, James Brown was old / till Eric B. & Rakim came out with “I Got Soul” / Rap brings back old R&B, and if we would not / people could have forgot.” Sampling is, first and foremost, an act of reverence. Of course it can put its very own spin on existing music, but it always enforces the notion of music as a universal language that is able to transcend space and time. In an ideal world, listening to hip-hop would be a family affair, where grandpa reminisces on the familiar melody while his grandson recites the raps. As Q-Tip remembered: “Back in the days when I was a teenager / before I had status and before I had a pager / you could find the Abstract listenin’ to hip-hop / my pops used to say it reminded him of be bop / I said, ‘Well daddy, don’t you know that things go in cycles?'” In some cases, such cycles even equal a bloodline.

The late Eazy-E’s uncle was Charles Wright, who lead the Watts 103rd St. Rhythm Band, whose “Express Yourself” was sampled by his nephew’s group N.W.A. Cold 187um, musical mastermind of West Coast pioneers Above The Law, is the son of Motown songwriter Richard Hutchinson and the nephew of Willie Hutch, author of “I’ll Be There” and composer of the scores to ‘Foxy Brown’ and ‘The Mack’. Above The Law affiliate Kokane is the son of soul arranger Jerry Long. Robert ‘Squirrel’ Lester of the Chi-Lites is the father of South Central Cartel member Havoc the Mouthpiece. Organized Noize producer/vocalist Sleepy Brown is the offspring of Jimmy Brown of funk band Brick. Shawnna (Disturbing Tha Peace, Infamous Syndicate) is the daughter of blues legend Buddy Guy. Bar-Kays member James Alexander fathered a certain Jazze Pha. World famous South African jazz pianist Abdullah Ibrahim has a daughter who goes by the nom de plume of Jean Grae. DJ Roc Raida’s father was a member of Sugar Hill act Mean Machine. Cypress Hill percussionist Eric Bobo is the son of jazz percussionist Willie Bobo. As a child, Chino XL was on the road with Parliament/Funkadelic, whose founding member Bernie Worrell is his uncle. Veteran hip-hop producer Salaam Remi is the son of Van Gibbs, a ’70s R&B producer who also worked with Kurtis Blow and the Fat Boys. Madlib’s father Otis Jackson, Sr. was a session musician for singers such as Tina Turner and Bobby Bland, his uncle Jon Faddis performed with Dizzy Gillespie and Charles Mingus. Trumpet player Olu Dara has not only actively attempted to bridge the generation gap on his son Nasir’s albums, he’s also played with jazz drummer extraordinaire Art Blakey.

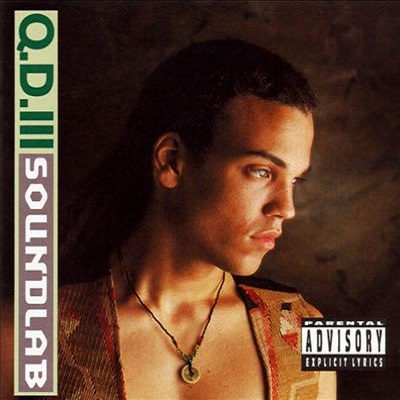

If that doesn’t prove that hip-hop is an updated form of existing traditions, I don’t know what does. Still, with the exception of Nas, the abovementioned hip-hop artists haven’t exactly been vocal about their parents’ profession. Even though it very likely helped them get a foot in the door of the music business. Then again, a famous last name can also be a burden. From that point of view, no one had to carry a heavier burden than Q.D. III (alternatively credited as Quincy D. III, Q.D. III, QDIII and QD3). We know him for his beats on 2Pac albums from “All Eyez on Me” to “The Don Killuminati.” He’s worked with Ice Cube and affiliated acts Yo-Yo, Da Lench Mob and Westside Connection. He produced Too $hort and L.L. Cool J and remixed Coolio and Naughty By Nature. He scored ‘Menace II Society’. He composed the themes of TV series such as ‘The PJs’ and ‘In the House’. He laid down beats for every single episode of ‘The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air’. He executive-produced ‘Tupac Shakur: Thug Angel’, ‘The Freshest Kids – The History of the B-Boy’ and the ‘Beef’ series.

Despite the almost 20 years he’s been in the game, Q.D. III has kept a relatively low profile. Which is even more astonishing considering he’s the son of one of America’s most popular and respected composers and producers, Quincy Jones. Quincy Delight Jones III was born in London in 1968. His parents would soon divorce, leading him to move with his sister and his mother to her native Sweden at age four. There young Quincy got into breakdancing, bought a drum computer and started producing demos for local rap artists. He played one of the lead characters in a Swedish film about youth violence, ‘Stockholmsnatt’. Simultaneously he also put out some of the very first Swedish rap songs together with Pop-C, with which he formed the group Bezerk. Their single “Stockholmsnatt” b/w “Next Time (It’s Your Brother)” went gold. At age 17 Quincy relocated to the States, briefly attending the Berklee School of Music in Boston and pursuing his dream to produce rap records in New York, where he was a witness to the proceedings at Power Play Studios. His first stateside productions include T La Rock’s “Nitro” and Special K’s “Special K Is Good,” both from 1987.

If it’s true that the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, Q.D. III’s career doesn’t seem that unlikely. Still, his dad must’ve cast a huge shadow. Quincy Jones is an icon. Produced both the best selling album (“Thriller”) and the best selling single (“We Are the World”) of all time. As a young trumpeter and arranger worked with jazz greats Lionel Hampton, Count Basie, Dizzy Gillespie. Produced ‘The Color Purple’. Scored the themes of ‘Sanford and Son’ and ‘Ironside’. Founder and publisher of Vibe Magazine. Co-owner of Spin Magazine. Won 4 Oscars. 28 Grammys. A Harvard chair, the “Quincy Jones Professorship of African-American Music,” in his name. First African-American to hold an executive seat at a major label. Produced Ella Fitzgerald, Aretha Franklin, Barbara Streisand and Frank Sinatra. Try filling those shoes.

In 1989, shortly before he would be celebrated in the documentary ‘Listen Up: The Lives of Quincy Jones’, The Dude returned with the ambitiously all-encompassing black music album “Back on the Block.” Its highlight from a hip-hop perspective was the title track featuring Melle Mel, Kool Moe Dee, Big Daddy Kane and Ice-T, who rapped in unison: “Back on the block, so we can rock you with the soul, rhythm, blues, be bop and hip-hop.” The song was introduced by “Prologue (2 Q’s Rap),” which featured father and son Jones trading lines before they left it to the pros. Jones junior was assigned to programm some of the drums the greats would rap over.

It’s safe to assume that Q.D. III wasn’t intimidated but inspired by the success his father had in his profession. But he didn’t follow the footsteps too closely. Notice that he decided to become a hip-hop producer before his dad had officially been sampled for the first time. Although it has to be noted that Q.D. III certainly contributed to the peculiar pop appeal of Tupac Shakur’s music, he mostly stuck to hip-hop throughout his career. Unlike Quincy Jones, who left his jazz roots to find pop success. It goes without saying that Quincy Jones must’ve opened numerous doors for his son. Would he have scored ‘The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air’ and ‘In the House’ if his father hadn’t produced these shows? Would he even have considered scoring and producing motion pictures and television shows if his dad hadn’t done the same? If Q.D. III was a musical guest on ‘Saturday Night Live’ in 1990, did he arrange that all by himself? Probably not.

Nevertheless, there are enough pointers to indicate that Q.D. III was willing to do his own thing, and that his ‘thing’ was first and foremost hip-hop. Quincy Jones was instrumental in his son’s first (and to this day only) full-length, as it was released on his own Qwest Records. But it didn’t attempt to copy the cosmopolitan, African-American all-star cast of “Back on the Block,” this was a hip-hop album reflecting the Los Angeles hip-hop scene of its time (ca. 1990/91). At one point in the late ’80s Quincy D. III must have moved to LA, where he did a track for Everlast on his Rhyme Syndicate solo album.

Everlast was absent from “Soundlab,” instead it featured many fresh faces. The only one who got a lasting career out of it was Justin Warfield, who would (again with the help of Q.D. III) record a solo album before initiating band projects like The Justin Warfield Supernaut and One Inch Punch. He is currently engaged in electro/goth outfit She Wants Revenge. Credited as Justin Warfield with The S.O.U.N.D. but calling himself Sev W, the 17 year old owns the three first cuts on Q’s album. “Ridin’ With the Rhythm” is their attempt at a Eric B. & Rakim “Follow the Leader”/”Let the Rhythm Hit ‘Em” type track, including samples from both aforementioned songs and self-referential rap lyrics delivered in a cool tone.

“Steppin’ With the Sound” flips the same sample used that same year in Pete Rock & CL Smooth’s “Go With the Flow,” but a bit more animatedly. Referring to himself as native child and native son, Sev situates himself close to the Native Tongues, even expressively mentioning A Tribe Called Quest. At times on the smoothly bouncing “Season of the Vic” (also included in remixed form as “Season of the R&B”) it’s easy to mistake him for the Q-Tip of “People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm.”

Up to this point, Q.D. III follows the formula for contemporary East Coast hip-hop with expertedly layered tracks stirred up by the occasional break. But the young man was out to prove that he was more versatile than that. The next four tracks are on the dance tip, containing quotes from the standard late ’80s dance repertoire like “Hear the drummer get wicked,” and “I know you’re gonna dig this.” Kenyatta’s new jackish “I Need” promotes respectful relationships, while he gets socially conscious on “Gotta Do More,” where over a house rhythm he raps: “Gangsters and soldiers are misled brothers / some kill for the love of money, others kill for their colors / The real color is the type of skin you’re in / Rebel against the enemy, or who’s not your friend.”

Kenyatta released a self-titled LP and was able to prolong his career until 2Pac’s “Me Against the World,” where he’s credited for background vocals. 213 are up next, but don’t expect to hear early recordings from Snoop, Warren and Nate, this crew was made up of DJ Ronski and rapper Glamorous G. The “One Nation Under a Groove”-sampling “Pumpin’ it Up” is a party track that caters to the group’s DJ, while “Hip Housin'” sees them presenting a “West Coast style of house music.”

Steering towards more traditional hip-hop again, “Soundlab” continues with “Livin’ in the Ghetto.” DJ Crazy Toones co-produces the high potent track that recalls the fat West Coast funk the Boogie Men laid down on “Death Certificate” and “Ain’t a Damn Thang Changed.” While WC contributes intro and adlibs, rapper Jazzy D, a recording artist since the mid-’80s, describes the everyday South Central madness:

“This ain’t a city, not the place that I’m from

Gangstas killin’ gangstas, all I see is a slum

Bums hangin’ at the liquor store, foamin’ from the mouth

fiendin’ for some cigarettes or a forty ounce

Nowadays, man, to stay in the hood

you gotta strap down like a black Clint Eastwood

Nobody cares if you bang or rap

Let ’em catch you slippin’ and they peel your cap

A million witnesses standin’ around and just cussin’

but when the police come, they ain’t seen nothin’

I know it’s sad, but I’m lettin’ you know

This is what happens when you’re livin’ in the ghetto”

LA’s Latin constituency is represented by soloist ST-One. “Set Up” has him spinning a tale of betrayal over a roomy, booming track, to which Quincy cuts up Slick Rick and KRS-One. As if to prove that he ain’t to be played, ST-One follows up with the album’s final cut, “Gigolo Lifestyle,” an explicitly funky affair where he spits game in a DJ Quik-like tone.

The remaining tracks lean towards the more free-form stylings LA would soon also be known for thanks to acts like The Pharcyde and Freestyle Fellowship. Here they come courtesy of Poet Society, or rather their only vocal member, the Detroit-born, Hollywood-based Kev (AKA Very Equivalent Knowledge). On three shorter tracks, he delivers quick jabs over creative backdrops, quipping for instance, “Much as the old school fought and fought to put us on top / suckers like you will still flop.” He flips the same verses over two different beats, “Catastrophe 1” and “Catastrophe 2,” both distinctly jazzy, the first one more uptempo, the second one more free-flowing with seriously sophisticated drum programming. “Potty Train ‘Em” borrows from the Marley Marl sound library, but is still a grooving track that pauses for a quick break where Q.D. goes to work on the drum pattern. “Grim Reaper” finally is a dark, dense track with Kev in the role of the mic murderer.

Only momentarily held back by four not quite as remarkable contributions by Kenyatta and 213, “Soundlab” is a solid showcase of a talented, upcoming producer and a troupe of unknowns. The selection of artists shows a deeper insight into the local hip-hop scene, making this much more than a quest to find the next Young MC or Tone-Loc. The downside is that none of the rappers possess the charisma of the LA elite of the time. Still it’s a sight to behold just how much more went into this than into your average new millennium mixtape. Excellent drum programming, for starters. Also, this random selection produces a string of technically advanced vocalists. Lyrically, things may look a bit different, although it’s probably a matter of taste whether you prefer the straightforward narrative of ST-One’s “Set Up” or the drastic, dramatic tone of Obie Trice’s “The Set Up.” Ultimately, listening to “Soundlab” is a throwback to a time when a multitude of styles could co-exist on the same rap record. Q.D. III would take part in a number of controversial rap releases and along the way probably lost some of the innocence that marks his debut album. But throughout the years, he’s been living proof that musical talent most definitely runs in the family, even if its expression changes from generation to generation.