To build on a post I put together for the weblog Can I Bring My Gat (The City That Care Forgot), let me quote what I wrote under the impression of the havoc wreaked by Hurricane Katrina:

Some years ago, I was watching a documentary on New Orleans’ musical heritage, featuring some of the elders that were still around, and the youngsters that carried on the tradition. Although I was already vaguely familiar with what New Orleans represents for modern music, having been introduced to the likes of Professor Longhair, Allen Toussaint, The Meters, the Neville Brothers, the Marsalis family and Dr. John in the late ’80s, I still marveled at how a place could live and breathe history, not turning into a museum. But this was also at the time when Cash Money Records put out a string of successful albums, most notably Juvenile’s “400 Degreez” (which I still consider Mannie Fresh’s chef-d’oeuvre.) So I was slightly offended that once again hip-hop – and its close local cousin bounce – were kept seperate from more established forms of music, annoyed at how the burgeoning N.O. rap scene could be ignored in such a documentary.

Yet as I absorbed the disaster in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina from the safety of my home, I didn’t think of Master P or Birdman, TRU or the Hot Boys, I went for my funk and soul compilations and played the songs we have encoded for you today for our humble tribute to The Big Easy. You’re invited to research the city’s unique musical history, purchase records by New Orleans artists and to make any other kind of donation if you can.

Sixteen months later, the rebuilding of New Orleans and the other affected regions is finally under way and hip-hop found its way back into the headlines and into my consciousness with both acts of charity and words of criticism. Rap stars called for financial aid and donated substantial sums themselves. Mos Def recorded “Katrina Klap” (based on UTP’s local hit “Nolia Clap”), while Houston’s K-Otix captured the situation best with their interpretation of Kanye West’s “Gold Digger,” the internet exclusive “George Bush Doesn’t Care About Black People.”

To come back to the initial argument, within hip-hop New Orleans did get acknowledged as a pool of unique talent, despite the reservations parts of the hip-hop establishment held against its most successful labels, No Limit and Cash Money. But in their time, fans of Master P and Juvenile might have been just as guilty of ignoring what was happening on the other side of the fence. If it was for rap alone, I would have probably not heard what else New Orleans had and still has to offer to music enthusiasts.

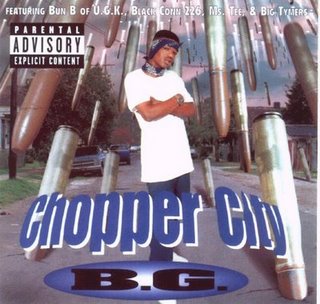

The Neville Brothers, sometimes referred to as the Crescent City’s First Family of Funk, have two particular albums in their catalog, “Uptown” and “Valence Street.” Cash Money artist B.G.’s 1996 album “Chopper City” contains countless references to that very same Valence Street and that very same Uptown. The reason is obvious – both B.G. and the Neville Brothers have strong ties to Valence Street. The former grew up there in the 1980s and ’90s, the latter, except for a brief period during World War II, when they lived in the Calliope Housing Development (that would later be home to the Miller brothers), spent their youth on Valence Street in the 1940s and ’50s.

In 2004, these two generations of NOLA musicianship would finally hook up when B.G. was featured on “Junkie Child” off the Neville Brothers album “Walkin’ in the Shadow of Life.” But compare “Uptown” and “Valence Street” with “Chopper City,” and you will have a very hard time believing that the Neville Brothers and the Baby Gangsta talk about the same part of town. While Uptown is arguably one of the most ethnically and economically diverse sections of N.O., a look at how both artists deal with Valence Street reveals experiences that seem worlds apart.

1986’s “Uptown” sticks mostly to love songs, its polished surface begging for mainstream acceptance. The ’80s had to draw to a close for the Neville Brothers to come into their own with the Daniel Lanois-produced masterpiece “Yellow Moon” LP in 1989 (followed by the excellent “Brother’s Keeper”). If anything, the Uptown of “Uptown” is a mysterious place where strangers succumb to the charm of the Big Easy. As Art Neville sings on “Midnight Key”: “You’re the New York girl, you seen it all before / but if I catch you Uptown on Valence Street I’m gonna melt you down to the core.” On “Money Back Guarantee (My Love Is Guaranteed),” they offer: “There ain’t much you can count on in this town / that’s why I’m speakin’ from my heart and I won’t let you down / My love is guaranteed.”

“Valence Street” from 1999 is musically much more down to earth. It features their collaboration with Wyclef Jean, “Mona Lisa” (from his crossover smash “The Carnival”). “The Dealer” is metaphorical and ultimately spiritual, and has nothing to do with drug dealers of any kind. Similarly, the Cate Brothers cover “Give Me a Reason” is on a search for solace: “Somebody tell me where I belong / and that’s where I’m gon’ be / Give me a reason and I’ll be strong / knowing there’s a place for me.” “Tears” honors the fate of Native Americans, while the title track happens to be an instrumental, where music alone is designed to evoke Valence Street.

Comparing these albums, wen can conclude that different generations of New Orleans musicians used different means to describe their environment, possibly because that environment had changed. By the time B.G. came into adolescence, what to the Neville brothers might have been Chocolate City, had to him become Chopper City, an image vividly conveyed on the cover with a hail of man-sized bullets raining down on B.G. standing defiantly in the middle of the road. Which was just a visualization of the metaphors found on the album: “Get your car doors bullet-proof / It’s rainin’ chopper, so get a bullet-proof roof, too.” But B.G. wasn’t just the weatherman, he let it rain himself: “Fuck with me, you gon’ learn / that chopper bullets burn.” Because “it ain’t no stoppin’ when the chopper get to choppin’.”

You have to extend your search to the rest of the Neville Brothers discography to find a clear reference to what B.G. talks about. “Line of Fire” (from 1992’s “Family Groove”) fits the description:

“War – the order of city life

where street signs are markers of battle lines

Here children disappear without a trace

The thrills of the treasure are poison-laced

Screams, oh screams, mama, you better run

Dreams, oh dreams, brother, give up that gun

(…)

Lines are drawn down every street

where neighbors are strangers who never meet

Guns are friends to anyone

You don’t know where the next shot is coming from”

The least thing I would want to do with this little experiment is to brand the Nevilles as living in some ivory tower occupied by traditional/professional musicians. As artists, they have repeatedly taken on the resposibility to address the ills of the world, from Aaron’s “Hercules” and “Jailhouse” to collective efforts like “Sister Rosa,” “Brother Blood,” “Wake Up,” “Run Joe,” “One More Day,” “Sons and Daughters,” “Let My People Go,” and “Broker Jake.” Nevertheless, Art, Aaron, Charles, and Cyril usually try to find a more universal form for what they want to say, as is customary in rock and pop music. They have the global view, sympathizing with Africa and Native Americans in their struggle.

As well-known ambassadors of the New Orleans music scene, the Neville Brothers represent the Nawlins of the black Mardi Gras Indians (their uncle assumed the role of Big Chief Jolly in the Wild Tchoupitoulas). They represent the hometown of Fats Domino and Louis Armstrong. They represent the city’s musical heritage and establishment (at least on the black music side), with the pull to have Keith Richards, Jerry Garcia, Linda Ronstadt and Carlos Santana accompany them in their sessions. Art and Cyril were members of The Meters, one of the most sampled bands in hip-hop history. Meanwhile, B.G., before his label’s fabulous deal with Universal (who re-issued “Chopper City” in 1999), was just a local teenage rapper.

A mere 15 years old at the time of recording “Chopper City,” Christopher ‘Doogie’ Dorsey was probably not the most far sighted person in the 13th Ward. Maybe he was just too busy staying alive. When a Neville Brother sings (on “Uptown”), “I do my best to stay alive,” you’re not sure what exactly it takes him to stay alive. B.G. won’t leave you guessing. He does “to clowns what they shoulda did to me.” “Chopper City” is full of kill-or-be-killed situations. As he put it a year later: “I either hurt or get hurt / it’s me or you on that shirt.” What kind of shirt, you ask? “T-shirts with pictures representin’ dead peers.” They must have been a common sight around his way, because he keeps mentioning them, warning, “They got a t-shirt waitin’ on your fuckin’ picture,” promising, “I put your face on a fresh tee,” and admitting, “I put that nigga on that t-shirt that you be wearin’.”

There’s surely no shortage of lyrics that promote violence on this album. If you’re into rap, none of that will be unfamiliar to you, nor will the arguments that can be made for and against it. What’s perplexing is that “Chopper City” can portray a picture so different from what the Neville Brothers choose to present on albums recorded ten years before and three years after, respectively. If you ask B.G., “Uptown is the home of the car jackers / robbers, gangsta rappers, head-splitters and kidnappers.” “Uptown is a cage for monkeys and killers / gotta be realer livin’ round all these gorillas.” He seems to live in a horrible parallel universe where only the worst things happen. But if you pay close attention, the rapper talks about a very specific place – the street. He’s “comin’ straight from the streets of the UPT” and openly admits, “street shit is what I’m into.”

It is the exact same war referred to by the Nevilles in the aforementioned “Line of Fire,” but related from a first person perspective: “We ’bout to turn your block to a warzone / I’m warnin’ you to bring the little kids in they home.” “Straight stickin’ to the g code,” B.G. knows that if you live by that code, you also die by it. “If I live I live, if I die it’s cool / cause I know fo’ sho’ when I was hit that I was a fool.” Expectedly, B.G.’s war report relies heavily on dramatization. Sometimes to an annoying degree. The repeated claim that he’s the Big Tymers’ Uptown connect in their ongoing drug operations, for instance (“Niggas Don’t Understand,” “Order 20 Keys”). Or the misogynist macking coming from a minor (“Bat a Bitch”).

He plays the role of the hustler who can’t yet rely on this rap thing as a steady source of income convincingly, though. He’s surprisingly eloquent on “Play’n & Laugh’n,” convinced that he will make it one way or another, but arguing rationally that every success is based on hard work:

“I try to maintain, keep my head straight

But my surroundings says niggas want half weight

So what the fuck, all I see in here is negative

and I ain’t got too many positive relatives

People try to tell me right from wrong

But man, I think I’m grown

I ain’t respectin’ no nigga, since my daddy gone I’m on my own

So let me all be the B.G. I’m gonna be

And it’s a possibilty I might see a ki

on Valence Street, I want nothin’ but green in my hand

But I ain’t gon’ say nothin’ cause shit don’t always go as planned

I’m just go do what I gotta do with my hustlin’ skills

cause I know somewhere out here for me they got a mill

I’m go and get it, I ain’t waitin’ for it to come to me

If that was the case I’d be waitin’ till eternity

I’ma struggle and strive, drink some wine

I’m doin’ bad, but that’s fine, I got my hand on my nine

You can best believe I’m go and get mine

Now you can take this to the bank, nigga, I’ma die tryin’

(Man, I can’t be playin’ and laughin’

Niggas sittin’ around waitin’ on shit to happen

But if you want somethin’, do what you gotto do

Get out there and make yo shit come through)”

“Doing Bad” is an equally impressive effort, as B.G. lets his guard down to reflect on his situation: “I was turned out at a early age / on VL, not afraid / Rocks and a 12-gauge / Raised like a slave, caught up in that 13th cage.” What makes “Doing Bad” exceptional is that B.G. not only wishes to sober up from the rush of street life, he also admits to a very real addiction he would struggle with for years to come:

“My pockets empty and I’m loaded, that just don’t match

Two and two together, that’s why I’m where the fuck I’m at

On my ass tryin’ to make a power move

Servin’ niggas two birds of flour is sour but it’s a come-up move

I’m on that dope, it ain’t no secret, but that shit ain’t shive

How am I stay high, stay shive and get mine?

I can’t do it, so I gotta try to kick the habit

or that million I want, I might not never have it

I gots to try to keep my muthafuckin’ nose closed

or I’m gonna end up drove with no hoes”

The confession closes out with “So Much Death,” where B.G. remembers (among others) the father he lost at age 12 with lyrics filled with remorse: “All he wanted me to do is be cool, stay in school / but the dudes that I hang with rearranged the whole attitude / When he died I start hustlin’ to get paid / I did the opposite, I know you’re turnin’ in your grave.”

Ultimately, B.G. is equally influenced by notorious hustler figures, successful gangsta rappers and an unhealthy dose of personal strife. The Neville Brothers and many others would probably beg to differ when B.G. says, “I got two choices, rap or sling lley’.” But everyone would applaud the confidence that convinced him to pursue the one and not the other: “I got skills for double platinum, I’ma have it like that.” In 1999, he did reach platinum with his album “Chopper City in the Ghetto,” prior, independently distributed B.G. albums such as “Chopper City” having moved the tens of thousands of units that caused Universal to invest in Cash Money.

“My company on the move,” B.G. knew already then. Looking back, mid-’90s B.G. was still a fairly basic rapper getting outshined by guests Bun B and Mac. There’s the characteristic quirky lilt to his voice, but he hasn’t yet switched to the melodic flow he adapted later on. Producer Mannie Fresh’s genius is in an embryonic state as well. Assisted by Odel on keyboards (later at No Limit credited as O’Dell), he puts together a few solid tracks. “Uptown Thang (Wait’n on Your Picture)” combines stuttering hi-hats and sparse, dark keyboard chords. “Niggas N Trouble” fulfills its function as the album’s smooth track, while “Play’n & Laugh’n” takes a clue from Oaktown’s E-A-Ski & CMT. Fresh interpolates ’80s material a few times (Zapp’s “Be Alright,” Fat Boys’ “Jail House Rap,” Whodini’s “Friends”), whereas other tracks lacking that kind of inspiration fall apart due to unsophisticated production.

It’s no surprise that the Neville Brothers cover “Drift Away,” a classic ode to music that talks about beats that free your soul, about getting lost in a band’s rock and roll, about guitars coming through to soothe you, about rhythm, rhyme and harmony helping you along and keeping you strong. While B.G., like many rappers, seems unconcerned about the music he raps to. And therein may lie the major difference between the two acts. To the Nevilles music and love offer an escape, to B.G. drugs and money promise that refuge.

It is not my intent to show up the young rapper while applauding the veteran musicians. Both artists have frequently made utterly conventional music. As the Neville Brothers vaguely dedicate their music to Uptown and Valence Street, B.G. is limited in a different way, left to verbally pledge allegiance: “Valence Street, nigga / Uptown for life, nigga / 13th, nigga.” Neither approach is particularly compelling. At the same time, these three albums are but moments in extensive discograpies. Both the Neville Brothers and B.G. have made honest, eye-opening music with direct relevance to their hometown, following a tradition of New Orleans musicians commenting on social life. And ultimately B.G. realized that to “represent Uptown to the fullest” he didn’t need to have the finger on the trigger “ready to pull it,” he just had to keep rapping.