It is not unusual for a British band to be well received in America. It happened to The Beatles. It happened to The Rolling Stones. It happened to Iron Maiden, to Judas Priest, to Radiohead, to Coldplay. In the early 1990s, it happened to The Brand New Heavies, albeit in a very peculiar way. The Heavies had formed in the mid-’80s (initially as Brother International) and were part of London’s acid jazz scene, a direct descendant of England’s northern soul and rare groove scenes, which can be characterized as dancefloor movements that favored danceable but unfortunately usually dust-collecting black music. Acid jazz was a modern take on this anachronistic preference of styles the international music business had long forgotten about. It added a modern touch to ’60s and ’70s soul, funk and fusion jazz, sometimes also by way of electronic equipment.

The Brand New Heavies themselves were a straight up band, whose appeal was that they were able to lay down a vintage groove without the use of samplers. The core trio of Simon Bartholomew (guitar), Andrew Levy (bass) and Jan Kincaid (drums) signed with the Acid Jazz label (founded in 1987 by Eddie Piller and Gilles Peterson) and released its self-titled, largely instrumental debut in 1990. The acid jazz movement itself dissolved in the greater whole of the dance explosion of the ’90s (drum-n-bass was just around the corner), but the Heavies were able to extend their recording career into the present, in 2006 reuniting with their most prolific lead singer, N’Dea Davenport, for the album “Get Used to It.” In the late ’80s, the American singer had signed an artist development deal with Delicious Vinyl, and after the label became the Heavies’ stateside distributor, she joined the band, who re-recorded its debut with her for the American market.

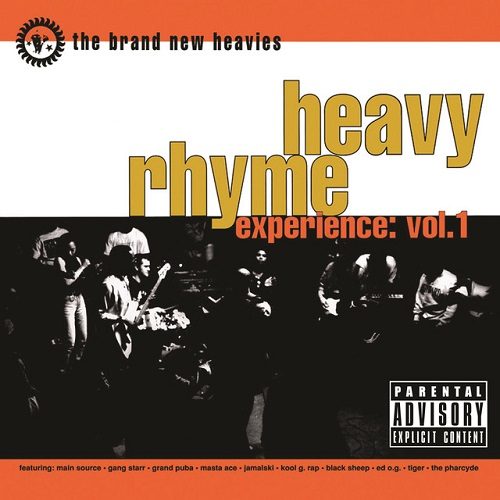

Fronted by a presentable and skilled singer, The Brand New Heavies quickly gained mainstream appeal, as evidenced by the success of 1994’s “Brother Sister” album. But even as a band without a steady lead singer, in some people’s ears the Heavies had struck a nerve. People who knew the value of a groovy instrumental and appreciated the band’s intent to – as one of their song titles put it – “Put the Funk Back in It.” People that used to look for those qualities in old records they would sample, and which they may not have suspected to find in a young band from Britain. Unless they had already discovered and sampled the tune “BNH” (which was the case for Arrested Development and Donald D). Legend has it that during their first show in New York, the Heavies were joined on stage by the likes of MC Serch and Q-Tip, who accompanied the encore with freestyle raps. It was this impromptu meeting of rap spontaneity and retro musicianship that brought forth 1992’s “Heavy Rhyme Experience: Vol. 1,” an album pairing the Heavies with some of the time’s hip-hop heavyweights and some notable newcomers.

Hip-Hop producer of note, Large Professor, leads the pack on the album’s opener, “Bonafied Funk.” The track approaches hesitantly, fading in slowly, as if the parties involved were conscious of the fact they were treading unknown territory. But once the instruments take over from the cheering crowd, the listener is dropped into the midst of a jam session where Main Source and The Brand New Heavies face off in a clash of fresh raps, lively basslines, percussive breaks, guitars licks, rhythmic scratching, horn stabs and groovy organs, crowd participation in the chorus contributing to the live scenario. The band conjures up its debut’s punchiest moments, causing the Queens rapper to note, “We got the Heavies in the crib puttin’ the funk back in it.” Soon after the release of “Heavy Rhyme Experience,” Large Pro and his two DJ’s would part ways, which definitely came as a surprise, considering how the enthusiastic Extra P involves K-Cut and Sir Scratch in the proceedings and exclaims, “It’s ’91, which means not a thing / cause for centuries we’ll make crews sing / No matter what record label, we stay stable.”

“Brand New Heavies / play the shit that people used to listen to in ’70s Chevy’s / so we don’t have to loop up a beat to funk your roof off,” P sums up the experience. Gang Starr must have felt similarly, having already professed their knowledge and appreciation of jazz on “Jazz Thing” and “Jazz Music.” Undoubtedly “Heavy Rhyme Experience” played a role in the conception of Guru’s own “Jazzmatazz” project. The title of their collaboration is “It’s Gettin Hectic,” a loose groove accentuated by horns that reflects Guru’s refusal to succumb to pressure. “I set it off by lettin’ you know that I can flow to many beats,” he determinedly offers. He adopts quickly to this one and has no problem falling back into the groove:

“Superficial styles only last a little while

but could never hold a candle to the Gang Starr profile

More than just wit and more than just intellect

And more than a gangster cause I kill with a mic check

And I’m not the one with the H on his back, meaning the herb

I like the funky beats, I like the good herb

most likely in a blunt, as I roll it real steady

Then I get mentally ready and play a track from the Heavies

and mellow out…”

Next up is Grand Puba, who echoes the sentiment to take it in stride on “Who Makes the Loot?,” assured that he rocks “hip” while “everybody’s rockin’ hype.” It’s hard to tell who’s stepping to who’s level, but fact is that the raps and the track match each other in their almost lazy approach, the Heavies applying a light touch with flutes and Stud Doogie adding cuts. It’s up to Masta Ace to make the band tighten things up. Ace had previously worked with acid jazzsters Young Disciples on their ’91 debut “Road to Freedom,” so he may have been past the need to rationalize what he’s doing here. Instead, “Wake Me When I’m Dead” is the conceptually most compelling song on “Heavy Rhyme Experience,” a collection of thoughts on rap careers and the music business over a somberly funky backing lit up by KRS-One’s sampled “Wake up!” yell.

While Ace previews the playful style he would flex on his first album for Delicious Vinly, “Slaughtahouse,” Kool G Rap is in full “Live and Let Die” mode, introducing sticker-worthy language to “Heavy Rhyme Experience.” “Brand New Heavies on the tracks, G Rap on the wax / cold pumpin’, got muthafuckas doin’ jumpin’ jacks,” he snarls on “Death Threat,” but rather than going all out, the band effectively builds up tension, supporting the graphic raps with its own interpretation of blaxploitation funk. Definitely a highlight in Kool G’s impressive catalog.

You would assume that three Londoners who are into music from times past would show little familiarity with the latest trends in American rap music. Yet several of the collaborations suggest that the Heavies knew exactly who they were dealing with. By their own account, they had been following hip-hop since the earliest days. Considering the rappers could not just ‘pick a beat’ as they usually would, it was up to the Heavies to come up with something that was in line with what the artist did at that time. And so “Who Makes the Loot?” didn’t stand out sonically when it was included in Puba’s solo debut “Reel to Reel.” “State of Yo” for Black Sheep possessed the same nuanced nonchalance the crew had just established. Ditto for “Death Threat,” “It’s Gettin Hectic” and the two tracks with ragga exponents (“Jump n’ Move” with BDP affiliate Jamalski and “Whatgabouthat” with the charismatic Tiger, respectively). These gentlemen didn’t just spend a weekend with “A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” “Wanted: Dead or Alive,” “Step in the Arena,” and other relevant recordings before going to the studio, they were familiar with contemporary rap in a way that made them just the band for such a project.

One act The Brand New Heavies couldn’t prepare for was The Pharcyde, who makes its official debut with “Soul Flower,” which differs from the version on “Bizarre Ride II The Pharcyde,” firstly in Romye and Fatlip’s verses, and secondly – and more importantly – in the backing. “Soul Flower” is the album’s grand finale, an incredibly natural sounding live jam, reviving the upbeat atmosphere of “Bonafied Funk.” The Cali quartet is eager to introduce itself to the world: “Oh what the heck, niggas just wanna get wreck to the track / it’s Brand New and Heavy as a Chevy, and in fact / The Pharcyde is comin’ and I hope we’re not wack…” “How long can you freak the funk,” they ask themselves, the band, and the audience, and you’re left with the impression that both the Heavies and the ‘Cyde could freak the funk way past the album’s playing time of 35 minutes.

The musical infrastructure of “Heavy Rhyme Experience: Vol. 1” is both familiar and different. As guitarist Simon told The Source: “When we made the rap album, we actually were like influenced by hip-hop. The way we played the music, you know, and structured it. So as musicians we were actually influenced by sampling.” The album is a testament to the liberal atmosphere of the early ’90s, when rap began to be seen as a legitimate and challenging new player on the contemporary music scene while rappers were open to try new things. A few begged to differ, such as MC Ren, who in the same year snapped, “I’m tired of rappers with live instruments on the stage / save the shit for parades,” arguing that “a real rap artist don’t need a band.” However, with the DAT and the DJ turning out to be limited live companions, rappers have since performed with musicians many times, some of rap’s biggest tours having been backed by bands.

But in ’91 such a venture was not just an experience, it was an experiment. As an adlibing Grand Puba says, “This ain’t no loop, this just some real live, funky, funky get-down-on-the-get-down (…) The bass player’s real, the drummer’s real (…) Everything is live, know what I’m sayin’? Year 2000. It ain’t just a simple loop, so don’t get souped.” He mentions the year 2000 as if they were molding the shape of things to come. Large Professor labels the collaboration “just an example of how rappers don’t have to sample to keep a funky beat on the street.” Looking at the current situation, it did remain just an example, as only one rapper/band combo (The Roots) has really been able to establish itself in the upper echelon of rap acts. Currently, producers often rely on studio musicians or their own ability to play an instrument. Entire bands are rarely trusted with hip-hop grooves, at least not in US hip-hop.

Maybe a “Vol. 2” would have solidified the point Delicious Vinyl and The Brand New Heavies were trying to make. That a rapper accompanying a band is just as natural as the same rapper flowing over creations of the DJ-turned-producer. Maybe it would have featured less functional tracks that primarily serve the MC’s and more intense collaborations like “Do Whatta I Gotta Do,” probably the album’s most promise-fulfilling moment, which pairs the Heavies with a nimble-tongued Ed O.G. Nevertheless, with not a single sung part, “Heavy Rhyme Experience: Vol. 1” is a highly consequent realization, and the project’s spirit lives on, whether it’s in the revivalist soul of Amy Winehouse and Sharon Jones and the Dap Kings or in the sampling renaissance in rap music. The ’60s and ’70s continue to be an inspiration for modern pop music.