In the summer of 1989, a motion picture hit theaters that was a morality tale with a decidedly inconclusive moral. _Do the Right Thing_, the Spike Lee Joint that made its author an internationally renowned director and a regular participant in the national political discourse, chronicles a sweltering hot summer day in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood in- and outside of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria, its parallel plots highlighting the constant friction between young and old, man and woman, father and son, boss and worker, and particularly between white, black, Latin and Asian in the melting pot that is New York City. The filmmaker’s father Bill Lee composed a playful, dreamy soundtrack that offers glimpses of the potential harmony humanity could live in. It is loud rap music, more specifically “Fight the Power,” a song written for the movie by militant group Public Enemy, that disturbes the peace evoked by the score and eventually provides the spark that causes the powder keg to explode.

The tension mounts whenever the character of Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn) enters the picture, his boombox relentlessly blasting the pumping rhythm of “Fight the Power.” His music, however, while playing a pivotal role in the escalation of events, is not the main cause for the eruption. In fact, the film works so subtly that the tragic turn of events is put into motion by two business-minded characters who up to this point had shown little inclination to join in the racially loaded back-and-forth. And yet it is Sal Frangione (Danny Aiello), the owner of the pizzeria, who by destroying Raheem’s radio launches a scenario that ends with the latter’s death, and it is Sal’s employee Mookie (Spike Lee), who, after Raheem dies at the hands of the police, throws a garbage can into a front window, inviting the furious crowd to trash and burn the place.

Two months after the film’s premiere, reality would provide a bitter commentary. The most outspoken opponent of Sal’s was Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), who was offended by the fact that the pizzeria’s “Wall of Fame” only depicted Italian Americans and that the Frangione family lived away from its business in Bensonhurst while making money off a mostly black clientele. On August 23rd 1989, a 16-year-old African American from Bed-Stuy named Yusef Hawkins was killed in Bensonhurst while inquiring about a used car that was for sale. He was shot during a confrontation with a mob of Italian-American youths who suspected him to date a neighborhood girl. Hawkins’ murder lead to racial tension throughout New York and was remembered in rap songs such as Brand Nubian’s “Concerto in X Minor,” Chubb Rock’s “Treat ‘Em Right,” Lakim Shabazz’ “No Justice No Peace,” Kool G Rap & DJ Polo’s “Erase Racism” and 3rd Bass’ “The Gas Face (Remix).”

Meanwhile, in Trenton, New Jersey, Tony Depula got along just fine with his African-American peers. At least we can assume he did, considering the Italian American produced local rap acts such as Too Kool Posse, Ministers of Black, YZ, and Poor Righteous Teachers, whose classic 1990 debut “Holy Intellect” he was largely responsible for. In 1991, time had come for Tony D to try his hands at his own rap career, earlier attempts including a solo cut on the Jazzy Jay compilation “Cold Chillin’ in the Studio Live” and opening the aforementioned “Holy Intellect” with a guest verse.

At a time when respected and successful white producers like The Alchemist and Scott Storch are perfectly at home on either the underground or the commercial side of rap music, Tony D’s acceptance may not seem that noteworthy, but considering collaborators such as YZ, Poor Righteous Teachers and King Sun had a distinctly pro-black agenda, Tony D’s ethnic background is a detail interesting enough to inspire an introduction like the one above, yet ultimately proves the old saying that in hip-hop, it ain’t where you from, it’s where you at.

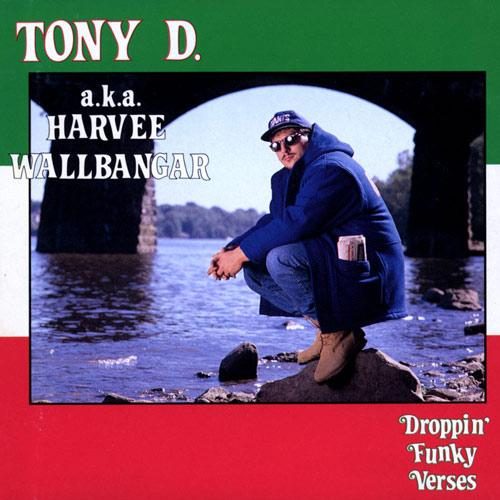

At first glance, you’d think that Tony D’s red, black, and green was green, white, and red. After all, the three colors of the Italian flag provide the background to the cover of “Droppin’ Funky Verses,” his only solo rap album. He had even spelled his heritage out loud (“I’m I-t-a-l-i-a-n / yeah, the lab technician”) on the ’89 track “Back to the Lab.” So one could expect Tony to create a specifically Italian identity to fit into the minority mold of hip-hop culture. Yet while he does use Italian signifiers, he doesn’t succumb to stereotypes but instead fights them (“My name ain’t Luigi, I ain’t at your car with a squeegee”). He realizes that in his position, before he’s Italian, he’s white. With the album’s second line, he already presents himself as “the flamin’ Caucasian,” making no bones about the fact that he’s white. He even goes as far as telling us that he’s “Tone with the skintone that seems to glow like snow.” But as keen as he is to draw a clear line between black and white, he at the same time pleads strongly for racial harmony.

“Stop Racism” is a festive track that starts with Tony recounting his own people’s difficulties when first arriving in America:

“Get it right, y’all, my family had to organize

Comin’ over on a boat, you see, they had to realize

that they were one, yes, in a nation of so many

nationalities of people, knowledge we had plenty

As an equal, but still some considered us an outcast

Names like guinea and wop is what was used in the past

to describe us, nonetheless we kept our head up

Knowin’ in the future we shall all drink from the same cup

Unity is what I’m strivin’ for, G, so let it be

Ebony and ivory in our community in harmony

Livin’ perfectly together as a whole

from the bottom of South Africa to the North Pole

When I look at a human you can say I’m color-blind

Cause I see them with my eyes but I judge ’em with my mind”

Regarding South Africa, history soon proved him right when he stated, “My conclusion to the topic will be racism must end / Apartheid you’re through is the message I send.” But while impatiently waiting “for the 21st century,” he must have realized that racism would not likely cease just because the calendar changes four digits. Still, Tone was convinced that because “some people will remain prejudiced / it’s my job to make ’em see through the fog and the mist.”

It may have been his own color-blindness that compelled Tony D to call out a duo of fellow white rappers that were less optimistic about humankind’s ability to look past skin color. Throughout “Droppin’ Funky Verses,” he makes snide remarks about 3rd Bass, MC Serch in particular. A RapReviewer can only speculate as to what the problem was exactly. A particularly wild guess would be that Tone thought Serch was talking about him when he said on “The Gas Face,” “Tony Dick gets the gas face.” Whereas that would have been Anthony ‘Tony D’ Dick, producer of Serch’s own solo singles on Idlers and Warlock. Be that as it may, Tony D took offense to several 3rd Bass characteristics, such as the apparently heretic name of one of their dancers, the fact that they beat down a Vanilla Ice lookalike in the “Pop Goes the Weasel” video, and a perceived identity crisis concerning their own color of skin, which made him question the duo’s missionary zeal: “You’re not the one to try to teach / people you can’t reach.”

“Don’t Fall For the Gas Line” makes a first attempt with rather weak wordplay like “Not with gas, I use diesel fuel” and “The weasels never rule” (which is pretty much what 3rd Bass hoped to get across when they called pop rapper Vanilla Ice a weasel). He even adopts what could be called black nationalist verbiage with phrases like “Your people equal bacon” and “You’re a devil.” The song’s most poignant statement (“I am who I am and that’s a fact / I couldn’t be somebody else, I wasn’t born to act”) is reiterated on “I Know Who I Am.” This diss succeeds better, as Tony makes the case that he’s not trying to be something he’s not, that “black is black, and white is white.” He spits more venom, for instance that Def Jam saw 3rd Bass as a substitute for the defected Beastie Boys:

“I know who I am, and you can clearly see this

Somebody else, there’s no reason to be this

type of person, but you say ‘What the heck’

And get no respect

Wearin’ sideburns that went out with Elvis

Thinkin’ you got soul just by pumpin’ your pelvis

Think again, you need to get out the basement

Cause to me you’re just another replacement

New hyped up Kids on the Block actin’ delirious

But rap’s not a joke, my brother, get serious

Suckers, yeah, we can surely pay ’em

If they act like the Beastie Boys until the AM

Step my way and I’ma school you like college

Nice no longer, so Serch for knowledge”

“Shoe Polish,” a CD and cassette bonus track, sums it all up with name-calling (“You no-soul havin’, knowledge-of-self lackin’…”), ridicule of Serch’s eyewear and microphone-holding technique, and the argument that explains why as a white rapper Tony D ultimately felt the urge to criticize 3rd Bass: “Puttin’ down your own people, that’s a pretty low level.” Being a producer first and rapper second, maybe Tony D had a more instinctive access to hip-hop, one that didn’t require him to rationalize his place in black music on an intellectual level the way 3rd Bass did. Pledging, “Watch me bust a rhyme on my man Arsenio Hall Show,” he simply thought he had what it takes to succeed in hip-hop, assuming that his skin color was of no consequence.

In view of all of this, the song “Harvey Wallbanger” is not without irony, as it basically mimicks 3rd Bass’ song “The Cactus” in the attempt to follow up BDP’s “Jimmy” and the J. Beez’ “Jimbrowski.” Nevertheless, “Harvey Wallbanger” is an entertaining ride with superb contributions from DJ Troy Wonder inserting well chosen quotes.

Which reminds us that Tony Depula earned his place in history as a producer. In fact, his 1989 instrumental album provided Naughty By Nature with the backing track to their 1991 hit “O.P.P.” His Two-Tone Productions credit is a definite quality seal for the 1988-1992 era. As a producer, Tony D deserves to be mentioned in the same breath as other late-’80s contributors to modern hip-hop production such as Howie Tee, Hurby Luvbug, The 45 King, Paul C, Teddy Riley, EPMD, et al. While it doesn’t top “Holy Intellect,” “Droppin’ Funky Verses” is still an impressive collection of what PRT front man Wise Intelligent once called “funky new radical tracks.” His choice of samples and drums resulted in a trademark sound. Often on a somewhat lighter note similar to Hurb’s work, Tony D’s tracks are dynamic and danceable, but where the era’s pop rap would have turned these samples into preppy workouts, Tony D never fails to insert them with hip-hop swagger.

The first five seconds of Hot Chocolate’s “Disco Queen” suffice to supply “Check the Elevation” with an uplifting intro and a strong rhythm track, the scratched hook giving it an extra edge. “Buggin’ on the Line” packs an even meaner punch, a funky bass guitar loop echoing loosely over a precise drum pattern. “Tony Don’t Play That” is a bare-bone track interspersed with differently toned melodic bits as the rapper gives you “a reason to play this – it’s probably the rawest shit on your playlist.” “Birdie Disease,” while not the rawest shit, is a successful realization of the song’s crackfiend metaphor, down to chirping scratches. The hard-hitting “Shoe Polish” pulls no punches (think “Takeover”), proving itself worthy of a battle track. The title track, like other Two-Tone productions, could use some sampled drums and a more natural sounding bass, but the sharp D.O.C. and KRS samples that make up the hook help ground the keyboard-infused beat.

While never reaching deafening Adrock intensity, Tony D usually raps at a high volume. At one point he even reasons that “with all this tooth-fairy, twinkle-toe, Peter-Pan rap it sounds good to hear somebody snap once in a while.” Yet he’s rarely aggravated, rather he develops a kind of theatrical style similar to the one utilized by The Pharcyde one year later. As a rock-solid rapper, he has the ability to calm things down temporarily. The 1990 single “E.F.F.E.C.T.” uses the same Sade sample as Paris’ “Mellow Madness,” as the Trentonian drops down to a conversational tone, not unlike Paris’ own performance. The soulful “Listen to Me Brother” (featuring what should be the group Ministers of Black), takes a strong stance against daytime radio, urging DJ’s to “stop sleepin'” and program directors to “wake up.”

On “Keep on Doin’ What You’re Doin’,” Tony D forfeits the sympathies earned with “Listen to Me Brother.” Once again radio is in his scope, but oddly, this time the attack is aimed at rap music. At a crucial point in the song the word ‘west’ is edited, but it’s clear as day that he literally calls the West Coast “a home for the sell-out,” making the pointless argument that “the home of hip-hop is the Bronx.” He may have someone specific in mind when he talks about a “wack style of rhyme” and accuses the anonymous opponent, “For an extra percentage point you’ll do anything / for a video you’ll let them tie a string to your back,” but discrediting an entire coast is as misguided an attack as any in hip-hop history, and an early example of East Coast ignorance.

The harder they come, the harder they fall. Tony D has a lot of good advice for rappers. He tells them to write creatively (“Not just another rap and then a dull-ass hook”), to be their own critic, to have passion and to strive for perfection. But as he tells others to “create a new level in your rhymin’,” he himself often takes the basic approach, rhyming “quickness” with “sickness” and “thickness,” boasting about being able to afford cordless mics, claiming to “dance even dirtier than Patrick Swayze.” Occasionally, his word associations are charming, but they certainly don’t reveal a conceptually advanced rhyme writer: “…I like to eat smelts and other fish / like candy cause it melts in your mouth / and it’s also good brain food / Since you’re a lame dude you should eat a whale / crude oil spilled over from the Exxon Valdez / It was the captain’s fault / that says the media – Really, but what do they know? / Sittin’ home twiddlin’ their thumbs in Play-Doh…”

“Droppin’ Funky Verses” is a solid album that doesn’t promise more than it can deliver. Compared to state of the art releases such as A Tribe Called Quest’s “The Low End Theory,” Ice Cube’s “Death Certificate,” De La Soul’s “De La Soul Is Dead,” Naughty By Nature’s “Naughty By Nature,” Ice-T’s “O.G. Original Gangster,” Black Sheep’s “A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing,” N.W.A’s “Niggaz 4 Life,” and last but not least 3rd Bass’ “Derelicts of Dialect,” it was undeniably out of date, a couple of killer cuts notwithstanding. Sadly, its sole significance lies in Tony D’s issues with MC Serch and Pete Nice. Added up to one track and put a bit more eloquently, his accusations would have carried more weight, and, if 3rd Bass hadn’t broken up, might have sparked a fruitful debate. Because this was more than a mere battle for credibility. Going past the matter of which white boy is more down, Tony D attempts to demonstrate how whites can participate in a black artform. He briefly refers to his Italian heritage, but in general shows and proves with skills on the mic and behind the boards.