“See, through my education illustrations were the key

See, where I’m from only busters have to pay a fee”

(Eightball, “Break-a-Bitch College”)

If there’s one thing you need to listen to rap, it’s imagination. IMAGINATION.‘The act or power of forming a mental image of something not present to the senses or never before wholly perceived in reality,’ as the 1637-page edition of Webster’s New Encyclopedic Dictionary sitting on my bookshelf defines it. But imagination requires inspiration. If that dictionary would just list words without attempting to explain them, it would only serve for spell-checking. By describing an action or a quality, dictionaries help us understand the meaning of a term, provided we know what the words in the definition mean. So in order to be able to envision something, we need clues and pointers. The more we get, the more accurate the image we conjure up in our mind. If too much is left to the imagination on the part of the one providing information, we might very well not get the picture.

Probably the most traditional way to spark imagination is storytelling. Everyone can tell a good storyteller from a bad one, as the former is able to let characters, places, and events come alive. That’s why stories need fleshing out. Rap regularly resorts to storytelling, often even in ways that leave a listener unaware that a story is being told. But whatever you call rap’s particular approach to formulating thoughts and relating events, imagination is required to make sense of a rapper’s words. Because a rap is nothing but words. No matter how vivid or vital these rhymes may seem, they’re only words. If they appear to be vivid and vital, that means the rapper succeeds in capturing your imagination. Imagination is an important tool in social life in general. Empathy, the ability to put yourself in somebody else’s position, has a lot to do with imagination. In rap, like in real life, it takes an effort on both sides. Are the signals that the transmitter sends clear? Is the receiver fit to interpret the information correctly? Human communication is full of misunderstandings, so we should not assume that we understand everything a rapper says the way he means it. You can bet that this publication right here misinterprets what rappers say all the time, just like an x amount of readers regularly misinterpret our findings.

A popular figure of speech is to read between the lines. While the ability to read between the lines can be a helpful skill, it requires that you are familiar with the topic and the verbiage. Few of us would be able to read between the lines of a diplomatic note, for instance. Only after years of marriage a husband can hope to be able to read between the lines of his wife’s suggestions. Rap music with its excessive word count has its very own way of beating around the bush. But not in the sense that you should have to read between the lines. Rap is usually more or less up-front. (For some too up-front.) That is not to say that raps always have to be self-explanatory. It is part of this expression’s appeal that it has to be deciphered and digested. The hip-hop prodigy who instantly grasps the meaning of every single rhyme that was ever scribbled down and recorded does not exist. There are too many different eras, regions, lifestyles, personalities represented in rap music.

The interpretation of rap has become something of a sport, last but not least for the writers involved with this website. That’s why not just the MC who can drive his point home, who’s clear and concise, the verbal pugilist who knocks his opponent out undisputedly, but also the one that makes use of poetic concealment, of clever wordplay, of figurative language, is admired. Even the most unimaginative MC’s use figures of speech that are exclusive to rap, such as ‘to rip the mic’ or ‘to spit 16.’ Not to mention, battle rappers rely heavily on the force of imagination, both their own and the audience’s. You won’t get far in a battle if you just tell your opponent that he sucks. It’s all in how much he sucks. It doesn’t suffice to tell him to run and hide. You gotta give him a reason to run and hide. Storytellers need to be resourceful too, cause ain’t nothing like a little dramatization of events to keep listeners at the edge of their seats. And finally we have all the rappers who embody a particular character (the gangster being the most widespread), who also depend on the listener’s ability to form a mental image inspired by words and music.

What does this have to do with Eightball & MJG? There’s more to the Memphis duo than meets the eye. And how do you perceive that? Exactly. Imagination. While the title of their second full-length is derived from a song on the topic of jail, it accurately describes the situation artist and audience find themselves in. As rap representatives from the outer reaches of a New York-centered universe, they were for a long time locked out and left looking in. As Eightball says in “No Sellout”: “Tell me what’s goin’ on, damn, I need help to see / I have chains on my brain from the strain of the / mental corruption eruptin’ through this industry / all I see is New York rappers back and forth on BET.” By the same token, as listeners who cannot share Eightball & MJG’s biographical background, we are also on the outside looking in, the album of the same name providing us with a look into the minds and hearts of these two “pimp-tight, black, strong, young, level-headed Tennessee hustlers.”

While it was this album’s successor “On Top of the World” that inspired this lecture (think “What Can I Do,” “Friend or Foe,” and “Hand of the Devil”), there are plenty of instances where “On the Outside Looking In” deals with the visualization of a situation. They range from elementary to elaborate. From “Hard times made a nigga write a lot of hard rhymes” to…

“In ’93 I was rappin’ about my curls and my Cadillac

the pimp blast, takin’ you fast, smokin’ grass and all that

Players got the message, busters didn’t attempt to listen

thinkin’ that we was talkin’ about that on-the-corner fake pimpin’

Hell yeah, I am that player from the underground

Hard black assassin from the neighborhood of Orange Mound

They don’t understand why, they being society

The white people who run this nation got somethin’ against me

Me bein’ a young black male with an education

teachin’ this pimpin’ so the blacks will one day rule this nation

But every day another brother tries to kill me

jack me because of the poverty in communities

where you either have to sell crack or jack, man

What I’m tryin’ to stress to you is don’t step to the fat man

because today I’m rappin’, rockin’ shows and pullin’ hoes

but tomorrow I might be on the cut slingin’ dope

See, in the studio I’m killin’ fools vocally

but if it came down to it, I could do it silently

Fuck the President, the media can quote me

Listen to them lyrics, fool, I ain’t sellin’ out, gee”

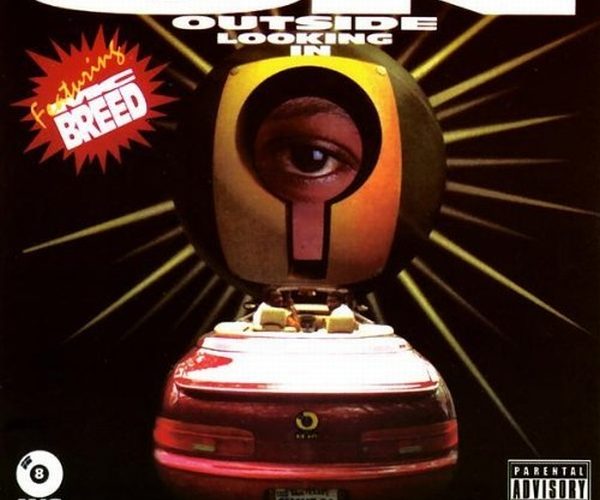

Jay-Z once asked, “How can you fairly assess something from the outside looking in?” He was right. You can’t. The phrase ‘on the outside looking in’ implies that the viewer’s scope is limited. But in art, that scope is determined by the artist. He decides just how much of his world he wants you to see. Think of it as an ancient peep show, where spectators paid to catch a glimpse of rare, realistic sights displayed in a peep box. It’s not a peeping Tom situation where rap fans voyeuristically peer through holes in the wall. We are invited to look. And if we take up the invitation, we are forced to take on the artist’s point of view. As Eightball demands in “So What U Sayin’,” “Buster motherfuckers need to open they eyes and look at the world as I see it.” You may not consider yourself a buster motherfucker (told you rap was up-front), but that includes you too. He adds, not quite as coherent, “but to me a nigga never will / comprehend two dimensions that I send which is real,” which I take as meaning that rap has its limitations in relating reality. Because you just can’t fairly assess something from the outside looking in. Rap is life through the keyhole, would be my own interpretation of this record.

His partner in rhyme MJG takes a slightly less pessimistic approach when he says in “No Sellout,” “Dear critic, you thinkin’ on terms on how it needs to be / I’m tellin’ you how it is and what I has to live and what I got to give / to the ears of the ones who wanna listen / some don’t understand, so they really don’t know what they’re missin’.” Maybe those who don’t understand just don’t have enough additional information to understand. Or it could be Eightball & MJG’s fault, if they weren’t so visibly concerned with visualization. Check “Anotha Day in Tha Hood” for some MJG-style imagination: “It was kinda hard as far as I could see / growin’ up in the Orange Mound, Tennessee community / Could it be the future had love for a nigga who / struggled through all type of shit for a bill or two?”

The great thing about “On the Outside Looking In”‘s title is that it really works both ways. Throughout the album Eightball & MJG point out that they are also in an outsider position. Whether it’s G admitting, “I’m a community outcast,” or Ball looking out from the inside and feeling compelled to compare in- and outside: “Television got me wantin’ to live like the white man / so I take a look around my neighborhood, liquor stores and pawn shops / coverin’ every fuckin’ block.” Only to realize that the world is a ghetto: “I don’t know what is worse, livin’ bad or livin’ good / but the whole world remind me of my neighborhood.”

It has always been rap’s claim to represent a reality. Eightball put it this way on his first solo album: “Many say the negativity shouldn’t be glorified / eyes wide open when they realize a nigga live and die.” Therefore an album like “On the Outside Looking In” aims to give up the real song after song. “Lick’em up Shot” shows how quickly an outsider is perceived as an “enemy, meaning he’s not down with me / meaning he didn’t come up in the motherfuckin’ Mound with me.” “No Mercy” tells a “true tale” in the form of a first person account from Ball, whose fast life comes to an abrupt halt: “I thought I’d party hard and smoke and drink this century / now I’m slowly dyin’ in this penitentiary.” The cautionary tale is extended into the following “On tha Outside Lookin’ In,” where MJG stresses his will to survive behind bars but ends on a similarly fateful note as his partner: “It’s hard to understand where I’m comin’ from if you on the outside talkin’ shit lookin’ in / Then again if you was on the inside lookin’ out nine times out of ten you would probably be my friend / Nigga how you figure the system gonna help ya? / The ghetto’s where they put ya, the ghetto’s where they kept ya.”

While they represent rap music’s fascination with the streets, Eightball & MJG never forgot to mention that they’re rappers. Because they fought hard to be rappers. And rappers who actually admit that they’re first and foremost rappers often have a clearer understanding of the symbolic nature of the street code they use. Eightball & MJG for example put pimping in a greater context, where it becomes a symbol for self-empowerment. That makes “Break-a-Bitch College” one case where you DO have to read between the lines of a rap song. Or concentrate on catching the lines that reveal its underlying message. And at the same time not lose sight of the fact that many other lines indicate that you should also take the song at face value. There’s no denying that Eightball & MJG are one of the most macho acts in rap history, and they do everything to keep their pimp act up. In another song Ball is ready to acknowledge that “mama showed love and she struggled for her only child,” but the rest of womankind gets no love whatsoever from the duo. Maybe it’s because if it did, their pimp reputation would be ruined. Maybe it’s because “niggas fightin’ for hoes and hoes pimp ’em well / and most of them busters end up dead or in a jail cell.” And yet as you listen to the absolutely hilarious and spectacularly scripted “Break-a-Bitch College,” pimping at least partially takes on a greater meaning in the world of these self-described Space Age Pimps. They are, ultimately, “talkin’ space age pimpin’, similar to the oldies / in ways like keepin’ our business tight, not by tryin’ to be Goldie.”

In 2007, with the release of “Ridin High,” Eightball & MJG look back on 16 years of recording. 1994’s “On the Outside Looking In” is one of several albums in their catalog that characterize what the South had and has to offer to hip-hop. It is both funny and serious, personal and political, relaxed and intense, and it always deals with the not so glamorous life.

Musically it still owes to West Coast rap, its p-funk variations “Players Night Out” and “Sesshead Funk Junky” paling in comparison. “So What U Sayin'” and “No Sellout” emulate the cinematic blaxploitation funk they’re based upon better, “Anotha Day in Tha Hood” is fairly creative for a track that interpolates “Mary Jane,” “Crumbz 2 Brixx” is an expedition into g-funk with original instrumentation, while “Break-a-Bitch College” packs some serious slow motion funk. The production handled by the artist and South O (which should be producer T-Mix) reflects the desire to meet the standards of established rap scenes and the intent to create something unique, evident in the menacing “Lick’em up Shot,” the bluesy title track, or in “No Sellout” flowing as thick as molasses.

“On the Outside Looking In” is not a rap masterpiece. But it’s an honest and intelligent window to the world of what so insufficiently is called gangsta rap. It is a landmark release of one of the music’s strongest scenes and a definite inspiration for all us rap fans who are blessed with a vivid imagination.