We always talk about hip hop in terms of East Coast, West Coast, or the South. It might make more sense for us to talk about it in terms of Eastern Europe, Western Africa, and South America, because hip hop is a global, not American, phenomenon. You are just as likely to hear DMX or Jay-Z blaring out of car stereos in Bratislava or Rio as you are to hear it in the Bronx. In the last twenty years, thousands of regional scenes have popped up across the globe full of hip hop heads reinterpreting the genre in their own tongue and for their own circumstances.

99 Posse (pronounced “nove-nove”) formed around 1991at a centro sociale in Naples, Italy called Officina 99. Centro sociali, or social centers, are kind of like community art and activity spaces, with a definite socialist bent. 99 Posse formed in order to have a vehicle for their political and social views. It’s fitting that they were from Naples. Like a lot of cities where American hip hop has flourished, Naples suffers from underemployment, poverty, crime, and corruption. There is also a lot of prejudice directed at Neapolitans, and the entire Italian South, by Northern Italians. In short, Naples is about as ghetto as Italy can get, and the same pressures and struggles that have inspired rappers in the US inspired the 99 Posse.

From the moment they were formed, the group was politically motivated. Like most of the Italian Left, 99 Posse were anti-imperialism, pro-minority, pro-immigrant, and sympathetic to communism. They were for marijuana and the working man, and against the government, the mob, and bosses. The anti-Mafia vibe in their music is in stark contrast to American hip hop, where the gangsta is often looked up to as an entrepreneur working outside the confines of the system.

99 Posse were also different from their American peers in that they were a musical group, not just a posse of rappers. The group included rapper Zulù, singer/rapper Meg Kaya Pezz8 on beats, JRM on bass, and Sacha Ricci on keys. They mixed rock, pop, techno, trip-hop, reggae, and hip hop into a Technicolor concoction that is not unlike the Black Eyed Peas, albeit less commercial.

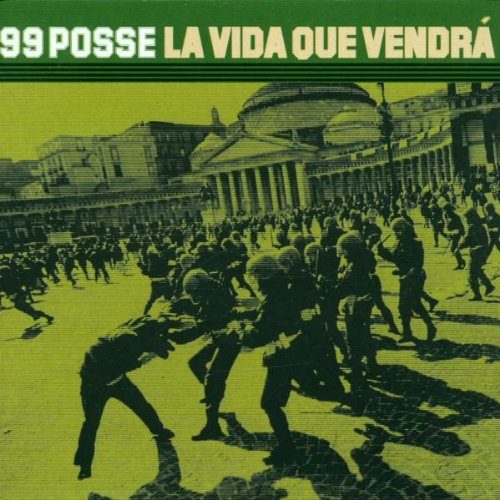

“La Vida Que Vendra” (Spanish for “The Life That Will Come”), their sixth and final studio album, came out in 2001. It was an exciting time for the Left, who were still feeling the adrenaline from the 1999 WTO riots in Seattle. The anti-globalization movement was in full swing, and there was an optimism that young radicals across the planet could unite and fight corporate dominance and put political and economic power back in the hands of the People. “La Vida Que Vendra” is brimming with the hopefulness and righteous anger of the time.

The album starts with “Commincia Addesso” (“It Begins Now”), a call to arms which features Meg and Zulu rallying against privatization and wage slavery. The song’s political lyrics and driving beat set the stage for the rest of the album. It’s followed by ” L’Anguilla” (“The Eel”) in which Zulu uses the eel as a metaphor for himself, slipping and slithering under the radar of the mainstream to subvert and sabotage. Over a bouncing beat laced with surf guitars, he lets loose one of my favorite hip hop disses ever –”va fa mmocc’a chi’v’e’ mmuorto”, a Neapolitan dis that means “go give head to your dead relatives.” I love their use of Neopolitan dialect. It adds a regional flavor that serves the same role as American hip hop slang, while making the finished product wholly Italian.

Another highlight is the rocking, bass-heavy “Esplosione Imminente” (“Imminent Explosion”), which is about all the whole breed of disaffected underclass ready to stand up against the system and fight the powers that be. Given the violence that the world has fallen into since this album dropped, the song seems eerily prescient. The most pop song on the disc is “Commutwist”, which laments how socialism has fallen out of favor in recent years, claiming that it is so out of mode to be communist that they dance the twist. For all its bouncy goofiness, it is rooted in solid convictions and lines like:

“E poi c’é la flessibilitÃ

a nuova moda a tutti ormai nota

che ci divide tutti a metÃ

chi more ‘e famme e chi va in Europa”

(And now there is the flexibility, a new way that has already been noted,

that divides the entire world in half – those who die of hunger, and those who go to Europe.)

I don’t know if the song was a hit in Italy, but it certainly had the possibility to be one. It was an ingenious way of spreading a serious message. Jay-Z may sport a Che shirt, but 99 lived it. This is further exemplified by “Povera Vita Mia” (“My Poor Life”), a dirge-like, mournful track that features a rapid-fire rant by Zulu about the struggles of the working class. He perfectly captures the feelings of frustration, anger, and hopelessness that are all-too common amongst the working poor.

One of the great things about 99 Posse is that they are inspired by American hip hop but create their own take on it. They don’t merely imitate 50 Cent or Nas or Puffy. The world does not need a bunch of global rappers sporting bling and trying to act like they are from the South Bronx or Caliope projects. We don’t need half-assed, foreign-language versions of American rappers. International hip hop works best when artists are able to flip the script and put their own stamp on the art form, creating a unique voice that adds to the culture as a whole.

“La Vida Que Vendra” isn’t 100% solid. Techno tracks like “Sub” or “Yankee Go Home” are pretty forgettable, and “Some Say This Some Say That” is an irritating pop-dancehall track. They also mellow it out on tracks like “A Una Donna” and “Sfumature”, both of which highlight Meg’s singing abilities. They are decent songs, but they also drag the album down a bit. Still, when it’s good, it’s great, and the combination of banging beats and revolutionary rhetoric is irresistible.

I’m not sure that someone without an appreciation for Italian music would be that excited by this disc. It can’t begin to compare to Public Enemy or even Rage Against the Machine as far as political rap. The broad musical influences and styles on the disc might turn off some hip hop heads who don’t like any techno or trip-hop in their music. However, “La Vida Que Vendra” is an excellent document of the impact hip hop has had on the world, and how other cultures have adapted hip hop into their own. It is also a eulogy of sorts of the optimistic radical anti-globalization movement that has been irreparably changed and transformed in the wake of 9/11, the riots in Genova, and the war in Iraq. Listening to this disc, I can’t help but think of the Wu’s question – “Can it be that it was all so simple then?”