All hip-hoppers are (to paraphrase KRS-One) out for fame. Fame is one of the main driving forces to become actively involved in hip-hop. With many American rappers seemingly overnight turning into stars, it is safe to assume that often it is the top-level success that inspires someone to pick up a mic. But there is a certain age at which another kind of fame is much more important – the fame among peers. It is a period when you ever so often disregard your elders’ advice, while the slightest attention from fellow teenagers seems to validate your very existence. Respect, fame, props, popularity – all those terms are, in hip-hop vocabulary, interchangeable. To claim that demanding respect is true to hip-hop while striving for fame is not, is nonsense. Still there is a difference when you seek the approval of someone – such as fellow hip-hoppers – who understands what you’re doing. And yet if these efforts wouldn’t radiate beyond the likeminded, graffiti artists would still be regarded as vandals, MC’s would have never signed with majors, and former b-boys wouldn’t tour with renowned dance companies.

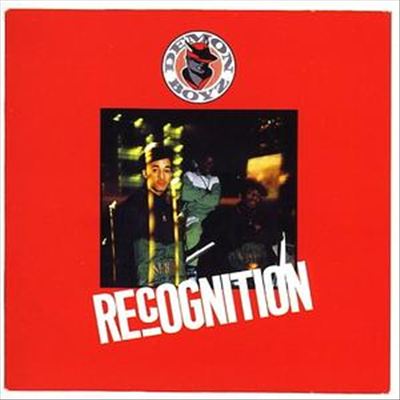

Since hip-hop has always been public art (staged virtually in the streets), sooner or later the world had to take notice. But if the four elements wouldn’t have a broader appeal than just to those who know what the hell is going on, most of us would have never known it existed. If its practitioners wouldn’t have aspired for universal recognition, hip-hop would have never left the South Bronx. The task of gaining recognition presents itself over and over again to the culture’s newest recruits. The longer it exists, the more groundwork is being laid. But pioneering efforts may still be needed depending on location, color of skin, creed, etc. To establish rap on the British Isles for instance took some time, but in the late 1980s the first full-lengths started rolling in. London’s Demon Boyz were among the very first with the appropriately titled “Recognition.”

The Demon Boyz consisted of DJ Devastate and rappers Demon D and Mike J, all hailing from North London’s Tottenham district. In their mid-teens, the latter were already participating in local sound systems. They were officially discovered when they won a competition held by a radio station handing out a spot for one of its live gigs, which eventually lead to them being signed by early UK rap powerhouse Music of Life. In 1988 they made their first recorded appearance on the seminal “Hard as Hell!” compilation before dropping the singles “Northside” b/w “Rougher Than an Animal” and “Vibes.”

“Recognition” updated and intensified the Demons’ specific take on the US export rap. With both vocalists being born to Jamaican parents, they put a distinctly Jamaican Briton stamp on a still small music scene that largely busied itself mimicking American rap down to the accent. The Demon Boyz helped break these shackles with highly energetic and engaging tunes that made their combinaiton of hard-hitting beats and high-speed chatting seem like the most natural thing in the world. Compared to another pioneering fusion duo, Asher D & Daddy Freddy (of “Raggamuffin Hip-Hop” fame), the hip-hop outweighed the dancehall, particularly on the musical side.

With the exception of the previously released “Northside” and “Rougher Than an Animal,” which were put together by Music of Life head honcho Simon Harris, the production was taken care of by The Twilight Firm, a team consisting of Devastate’s older brother Brian B and Stevie Gee, who gave popular programmed drums their own hardcore spin and underpinned them with ragga basslines and funk breaks. The opening title track is a precisely ticking jump-up tune with superb vocal extras such as a crescending “Aaaaah-ya!,” Rakim and KRS-One quotes and most notably the MC Lyte sample “recognition” repeatedly cut up by Devastate. The dominant drum beat is further bolstered by strategically placed melodical bits and pieces. But it’s the MC’s enthusiasm that makes “Recognition” a hip-hop anthem. The two form a truly dynamic duo, feeding off each other’s energy, reconciling chest-thumping boasts (“Even Rambo will have to lay low”) with a message of peace (“Positive rhyming, no negativity”), while always complying with an MC’s primal urge to rhyme (to the point of making up words like “worldwideable”).

It is Mike J who brings a sense of urgency to “Recognition,” stating, “We’re not satisfied, that’s why I’m complaining / gaining, reigning, my ultimate aiming: / to gain recognition, to be recognisable / (Demon Boy crew) – not commercialisable,” and even getting carried away to a rare moment of strong language: “Open up your eyes, I’m wise, I emphasise / about fucking time we been recognised.” He also spins the oft-told tale of a persistent rivalry that ultimately leads to two rappers joining forces:

“In school me and Demon never used to get along

I’d say that I was right, he would say that I was wrong

We used to battle in a big spot

He used to try and win while I was on top

We both were number one, there weren’t no other

Then one day he became my brother”

Just so you don’t forget the third of the trio, “We Call Him DJ Devastate” is up next, a rugged romp with lively syllable-flipping. “Out of all the DJ’s he’s the one that I prefer,” states Mike matter-of-factly, adding ironically, “You guessed it, it’s a DJ track / featuring a DJ with a little slot of rap.” While the DJ part should have been longer after that statement, the song still achieves its goal to give the man behind the wheels nuff credit. The rapper goes as far as saying that “the days are over when they’d need a MC / DJ Devastate don’t need me or Demon D.” It was a time when UK DJ’s like Cutmaster Swift, Pogo, Biznizz, Supreme, and Undercover enjoyed hip-hop fame all over the world, and the Demon Boyz made sure to include their DJ in that illustrious bunch.

So far “Recognition” is a graduate of the Marley Marl school of programming, and to prove the point along comes “Vibes,” which is based on MC Shan’s “Juice Crew Law,” complete with “Get up, Get Into it and Get Involved” guitar samples. But that’s where the comparison ends, as the fast-paced patois over the dense drums make this just as much a precursor to drum-n-bass as a carbon copy of American rap. Lyrically, the track attempts to define the undefinable term ‘vibes’ (an issue readers of this publication may relate to). Mike J:

“When my Vibes are dirty then I guess I will be cleaning

Vibes I’m exploring, there’s no dictionary meaning

It’s a feeling coming from your heart, here’s my example

Vibes are in my body, mi say this is just a sample

This is one pence from a million pounds

one sand particle from a whole beach

one raindrop from a whole thunderstorm

never repeating, always altering form

We don’t conform to what you think is expected

I am not a president, I was not elected

See? And I do not teach

The Demon Boyz carry vibes and the vibes just reach“

It was this conviction that made them end the album with a brief (Audio Two-sampling) instrumental called “Gifted and We’re Going Far.” Later they would shortly be signed to an Island subsidiary and in 1992 release a second album (without Devastate) called “Original Guidance – The Second Chapter” with another indie before unfortunately abandoning their quest to go far. Last year “Recognition” was reissued by Suspect Packages and selected as the third best UK hip-hop album of all time by Hip-Hop Connection, the country’s premier rap publication. The laudation claimed, It’s “Criminal Minded” and “Critical Beatdown;” “Nation of Millions” and “Step in the Arena;” it’s “Kool and Deadly” too. Most importantly, though, it’s Absolutely Fucking Brilliant, and concluded: Sure, Demon Boyz weren’t the first to do British. But they were the first to do it so successfully across the length of a whole album – an album that still sounds fresh today.

In all honesty, even if the reissue has been freshened up, some tracks do show their age. “Northside” mimicks the mid-to-late ’80s gruff Bronx hip-hop that also spawned BDP and sounds accordingly dated. “Rougher Than an Animal” is musically patchy, vocally stiff and too obviously constructed as the crew’s introduction to the world. The reputation of these songs stems from the fact that they were on early singles while their role as album tracks is less relevant. “With a Z” impresses with an intense vocal back-and forth, but basically amounts to a lecture on how to spell their name. The anti-drug tune “Don’t Touch It” is patronized by guest vocalist Dizzy Ranks and strictly dancehall.

But the highlights make up for the few less spectacular moments. Count “Lyrical Culture” among the outstanding cuts. Demon D flows solo over crisp “Zimba Ku” drums interspersed with samples most longtime rap fans would associate with tracks by Eric B. & Rakim, Kool Moe Dee, L.L. Cool J and Boogie Down Productions. He gives a particularly charismatic performance, switching between Jamaican patois and urban English to exhibit nothing less than “Lyrical Culture”:

“This is my lyrical culture, no bite it like a vulture

Let me approach ya, I let my rhyme coach ya

Born in-a England, parents born in Jamaica

Change up my style, put my lyrics ‘pon paper

Call me democrat, call me illustrator

When I get the munchies I am a potater

Don’t imitate, don’t call me imitator

Create my own style, so call me creator

If I hate ya I will frustrate ya

Shine my gold teeth and smile like alligator

(…)

Now when I meet a girl I gotta infatuate her

Locate her and interrogate her

Open up her legs and then mi a-fi lubricate her

(…)

If you praise me then boy, I will praise ya

My lyrics they will daze ya, even amaze ya

Dance to mi music like it the new craze-a

(…)

Upon the mic I bubble like geysir

Organise all my rhymes, so call me organiser

Ask me how I do it, well, I ain’t no advisor

Yes, I’m making money but I ain’t no miser

(…)

Talk to me proper and I will socialise-a

Talk pure foolish, yes, I tell ya pure lies-a

In a special rhyme cause I am a specialiser

As I’m getting older, yo, I’m getting wiser”

London’s Soul Jazz Records recently released “An England Story – The Culture of the MC in the UK 1984-2008.” The Demon Boyz didn’t make the cut, but rap acts such as Ty, Roots Manuva, London Posse and Blak Twang did, accounting for both America’s impact on British black music and Jamaica’s continuous influence. “Recognition” might be seen as predating what was later in the US called ragga hip-hop, but as Hip-Hop Connection observes, This wasn’t some ‘ragga hip-hop’ contrivance, it was British rap. Almost twenty years later some people still frown at the idea of British rap. But in 1989 the Demonz went for theirs, exclaiming, “Recognition’s what I’m looking!” Without that attitude, Banksy wouldn’t be a hot commodity in the art world, Estelle wouldn’t chart around the globe with “American Boy,” and the DMC/Technics World DJ Championships 2000 wouldn’t have been held at London’s Millennium Dome.