Like many 30-something hip-hop heads my first exposure to the musical and lyrical stylings of Michael Franti came in the early 1990’s under the guise of The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy. Franti’s relationship to this group was much like BDP’s relationship to KRS-One – he was their sole recognizable voice and there simply wasn’t a group with him. This was entirely fair given that in both cases the politically charged dialogue of their frontman was what distinguished them from far more timid contemporaries. In fact early Franti may have had even more in common with the beat poet revolutionaries of the 1970’s than KRS-One. The DHOH song “Television, the Drug of the Nation” is as historically important to hip-hop as Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” and while the two songs came two decades apart they both recognized the power and danger of mass communcation’s ability to deceive the masses (or at the very least ignore the truth). The very fact these declarations were issued in mass media formats through corporate record labels is not lost on the keen observers, nor is the fact both struggled with said labels over creative control. Franti’s issues with creative control came to a head in 1997 when he left Capitol Records and ownership of his current band’s name “Spearhead” behind. All his works since have been called “Michael Franti & Spearhead” even though the concept was his before the split and still is today.

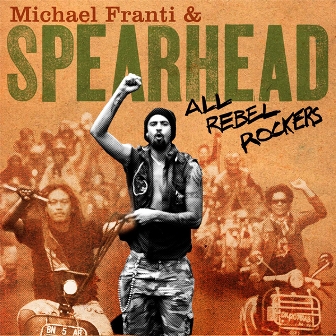

Having not covered Franti’s previous works including the aforementioned DHOH album until now has been a regrettable oversight. Equally shameful is the fact Franti néeSpearhead has slipped under the commercial radar since 1997, despite consistently recording and touring for the past decade. Having gotten a late pass to catch up on Franti’s work on “All Rebel Rockers” this writer was in for a bit of a surprise. Franti’s work even on early Spearhead albums suggested a larger consciousness of the African diaspora and a greater kinship to reggae than rap, although his no-nonsense delivery clearly suggested hip-hop first or at the most a poet rooted in hip-hop expression (a la Saul Williams). 2008’s “All Rebel Rockers” does not suggest Franti has completely forgotten these roots, as you can still hear his rap from time to time on songs like “Soundsystem”:

“Bedroom puttin on the uniform

Dialin the numbers on a xylophone

Starin at the mirror watch you transform

And makin sure they all know you all alone

And, blowin up the 20’s gonna blow the horn

Late night ticket for the unicorn

Everybody lookin for the same old porn

Oh could a DJ really save our soul now?”

Far more often though “All Rebel Rockers” suggests the Franti/Spearhead sound has been completely subsumed by the Carribean roots reggae style. This is not deterimental at all, just different from what one who lost touch with Franti would expect. “Rude Bwoys Back in Town” finds Franti asking the question for his audience: “Dem a say Michael, Michael, where you been?” Hanging out with Wyclef Jean I suspect. There’s something both authentic and odd about Franti’s transformation into a roots rasta revolutionary. He’s rocking to de riddim with the right cadence and swagger, but he doesn’t have the accent that a native of any of the island nations would spitting these words. The closest Franti gets to what might seem like mimickry is in pronounciations, but it’s definitely not done in a mocking way. Ironically that’s what makes Franti’s take so authentic – he’s not effecting a faux accent just to blend in.

It’s almost as though he and Wyclef have become flip sides of the same coin, and there are times on “All Rebel Rockets” that you might have difficulty telling the two apart, which is meant entirely as a compliment. Jean has dragged a lot of hip-hop heads, reluctantly or otherwise, into the larger world of African music through albums of increasingly diverse musical influence. While Jean brings his rap audience to the diaspora through his Haitian roots and love of hip-hop, Franti brings what at this point is certainly a reggae or African music audience a glimpse of a American’s admiration for righteous rebellious music. Franti no doubt sees himself as spiritual kin to Bob Marley and is far more the rasta than the rapper, though there’s just a hint of the Franti of his youth bubbling up beneath the surface. Songs like “Life in the City” suggest a sing-song rap approach to lyrical delivery that anyone from Akon to Nelly fans could appreciate, although the melody and tempo definitely won’t shake up the club. If anything they make you want to chill under a palm tree with a spliff of sensei.

Perhaps in the end this is the ultimate rebellion – the revolution won’t be televised, nor will television drug you into vapid mindlessness. “Hey World (Remote Control)” suggests a brand new way of “turn on, tune in, drop out” that’s more informed and astute – because as Franti says if you can “let go remote control” you can be more at peace with yourself and simultaneously aware of the world’s evils. Franti urges listeners throughout the album to “put up a fight” with injustice, yet the music is not angry – it’s a cool ocean of emotion. Franti’s “All Rebel Rockers” ranges from uptempo piano-rocking party anthems like “Say Hey (I Love You)” to funk out jams like “High Low” but all carry the African reggae vibe that Franti’s on now perfectly. This is not the Michael Franti that I expected from the 1990s, but it’s a welcomed evolution of his sound that will fit perfectly in my collection next to Burning Spear, Wyclef Jean or Sly & Robbie.