The figure of Tupac Shakur looms large, not just in the world of rap or entertainment, but in my own life. I remember bumping “I Get Around” on my Walkman and recording “California Love” off the radio, replaying it over and over so I could write down all the lyrics. I remember dubbing a friend’s copy of “All Eyez On Me” onto an unmarked blank tape so that my mom wouldn’t know what it was (do parental advisory stickers still ward parents off?). More than any of this, though, I remember the day he died – walking into my Spanish class, hearing the punk-ass white kids snickering about it and watching them laugh at my friend Bennicha for crying at the news. I remember kids using the lyrics of “Only God Can Judge Me” as an example of a cultural text in my English class, and the teacher actually listening respectfully. Then, just days later, I remember dealing with the death of my grandfather and feeling selfish for having poured so much grief into the death of a public figure.

So many conflicting emotions, all so indelibly imprinted on my mind, and I know my story is just one of very, very many. It wasn’t until years later – I was only 13 at the time of Tupac’s death – that I really delved into his life and music and came to understand what he meant to people, myself included. It was a journey that led me to devote my college and graduate education to researching just how this music could carry so much meaning and how its various components worked. More than a decade later, I still can’t say I fully understand, but the near universality of this strong sentiment for Tupac’s life and work is almost explanation enough.

In the midst of all this lies Shakur’s actual musical output, which is quite impressive no matter how you stack it. As unbelievable as it seems, he released only four albums before his death (the Makaveli album came out shortly thereafter). The rest of his massive catalog, which contains upwards of ten albums if you count the multiple compilations and remix projects that bear his name, was released posthumously and has played a large role in determining his legacy. With the considerable clamor to uncover ever more unreleased material, people often overlook his early work, which is a real shame. Because, for as captivating an artist as he was in his later years, he was even more fiery at the beginning. He just channeled his fury into a specific direction: the social and political injustice that circumscribes black life in the ghetto.

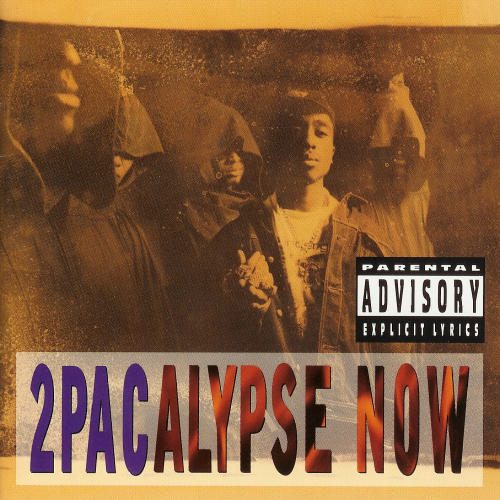

Nowhere was this focus clearer or more fully expressed than on his debut, “2Pacalypse Now.” For those who only know him from his “How Do U Want It” days, “2Pacalypse” may come as quite a shock as it is light years away from the Cristal-sipping opulence that characterized some of his more popular material. Both musically and lyrically, this album is another beast entirely, but it’s one that rewards heavily your listening investment. It may be less easy to digest than his Death Row work, but it is some of the most powerful stuff he ever recorded and is pivotal to any understanding of his artistic persona.

Musically, the album has not aged particularly well. It sounds dated, as well it should given that it was released in 1991. That’s almost 20 years ago now, which seems impossible, but it shows in the rough-edged production and poor sound quality. Much of it sounds like a muffled and less dense imitation of the Bomb Squad mixed with Shock G’s occasional flourishes on the keyboard. The result is an album of drum-heavy beats and abrasive synths, as if to remind you not to get too comfortable with such serious matters at hand.

And Tupac has plenty to discuss. None of it strays too far from the established topic, but he continually finds new ways to address the central issue. The album opens with “Young Black Male,” a double-time rap experiment that acts as an introduction of sorts with Tupac presenting himself to the audience as a prototypical black youth more than a unique individual. From there, though, it’s straight to business with “Trapped,” where he rails against the suffocating strictures of the ghetto and the society that keeps this unjust system in place. Through first-person narrative, ideological analysis, and incitement to action, he paints a vivid portrait of these circumstances:

“They got me trapped, can barely walk the city streets

Without a cop harassin’ me, searchin’ me, then askin’ my identity

Hands up, throw me up against the wall, didn’t do a thing at all

I’m tellin’ you one day these suckers gotta fall

Cuffed up, throw me on the concrete

Coppers tried to kill me but they didn’t know this was the wrong street

Bang bang, count another casualty

But it’s a cop who’s shot, there’s brutality

Who do you blame? It’s a shame because the man slain

He got caught in the chains of his own game

How can I feel guilty after all the things they did to me

Sweated me, hunted me, trapped in my own community

One day I’m gonna bust, blow up on this society

Why did you lie to me? I couldn’t find a trace of equality

Work me like a slave while they lay back, homie don’t play that

It’s time I let ’em suffer the payback

I’m tryin’ to avoid physical contact, I can’t hold back

It’s time to attack, jack… They got me trapped”

He tackles the same subject from a slightly different angle on “Soulja’s Story,” where he tells the tale of a young man struggling in a drug-riddled family who gets caught up in violence and crime amidst corrupt cops, only to see his little brother eagerly trying to follow in his footsteps. It’s classic Tupac in the way it depicts the seeming inevitability of such self-destruction without completely absolving anyone for the decisions they make. This ability to analyze and describe a situation in all its complexity without resorting to simple platitudes is a large part of the legacy he would grow into, and it was on display here as well.

The narrative approach serves Tupac well many times on the album, as he uses it for full effect in a number of songs. “Violent,” which drew the ire of none other than potato-man Dan Quayle, is a vivid recounting of the events that lead a victim of police brutality to fight back and go out in a blaze of glory rather than simply succumbing to the long arm of the law. The most famous of these story tracks is “Brenda’s Got A Baby,” deservedly hailed as one of Pac’s best, in which he runs down the life of a young mother turned prostitute and murder victim while capturing the confusion and lack of choices that weigh down on the girl. This one is characteristic of much of “2Pacalypse Now” in that it eschews the notion of a hook in favor of continued exposition. It’s almost as if he couldn’t be bothered to cut into valuable storytelling time to get your head bobbing.

This is never more true than on “Words of Wisdom,” where Tupac alternates between spoken word and rap to deliver an incisive critique of the hypocrisy of American society in terms that can’t be summarized. I’ll let him tell you himself:

“[spoken]

America! AMERICA! AMERI-K-K-K-A!

I charge you with the crime of rape, murder, and assault

For suppressing and punishing my people

I charge you with robbery for robbing me of my history

I charge you with false imprisonment for keeping me trapped in the projects

And the jury finds you guilty on all accounts

And you are to serve the consequences of your evil schemes

Prosecutor, do you have any more evidence?

[rapped]

Words of wisdom, based upon the strength of a nation

Conquer the enemy armed with education

Protect yourself, reach for what you wanna do

Know thyself, teach by what we been through

Armed with the knowledge of the place we been

No one will ever oppress this race again

No Malcolm X in my history text – why’s that?

Cuz he tried to educate and liberate all blacks

Why is Martin Luther King in my book each week?

He told blacks if they get smacked, turn the other cheek”

And just in case you weren’t sure of the continued relevance, he throws in a “Fuck you to the B-U-S-H,” which is satisfying no matter what era it’s from.

“Tha’ Lunatic” is about as light as it gets, as it features Tupac clowning around, dissing his (as yet unnamed) competitors and upping his own rhyming prowess. Even here, though, it’s never completely without an edge, as Tupac promises to leave you “bloody as a Kotex, snappin’ motherfuckers’ necks.” “Rebel of the Underground” starts off as a cocky romp through typical hip hop boasts but turns into another societal rant about – what else? – police brutality and white hypocrisy.

The album closes on its most melodic note, with “Part Time Mutha,” another first-person narrative, this time about a strung-out mom whose drug habit leaves her kids out in the cold, leading her son to resort to a life of crime. This song is also notable for the interpolation of the obvious source material, the first (but not last) time a Tupac song would draw from Stevie Wonder for musical inspiration.

It’s not an extraordinarily long album, but it is a dense and heavy listen that will take a lot out of you if you pay close attention to the persistent theme. The beats overall fail to make much of an impression, but perhaps that is as it should be, since nothing should be allowed to outshine this kind of lyrical performance. Tupac’s vitriol is carried by his sincerity and charisma, both of which would emerge as key traits of the figure that blossomed in the years to come. Over the course of Tupac’s career, the political got suffused by the personal and receded from the central position it occupied on his debut. On “2Pacalypse Now,” though, it is squarely in focus as he channels BDP and Public Enemy through the Black Panther lens imparted by his mother and the extended family of activists he grew up around, and the result is an eye-opening look at black ghetto life and a powerful introduction to an emerging talent. Do yourself a favor and get to know this one.