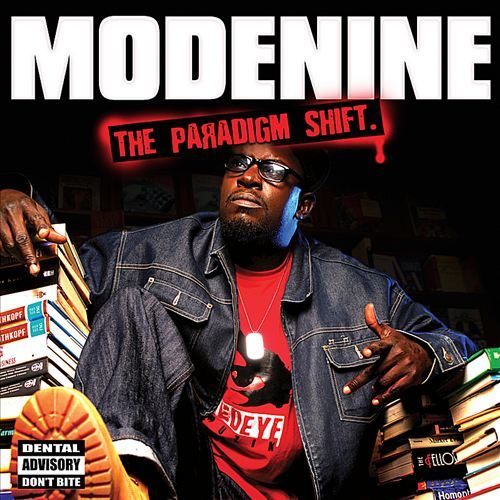

Modenine, who raps in Nigeria, is quite proud of his lyricism Рa good context, since he claims Nigeria is overrun by gangster rap and its silly, obvious clich̩s. If Nigeria really is a den of dullards, Modenine at least protects himself, and, cautious against biters, sports the unappreciative logos and quotes on his website and album. Fair enough, as the talentless, if they care enough, will crib from their betters, and the talented, if prone to indiscretions, might still get your head shaking.

And, let the head shake. Modenine (positively) compares himself to Wordsworth in one interview, with little explanation. Is that wise – these strange, out-the-genre expectations? Why do creative people, especially with some fame, ‘try’ poetry, or think of themselves as poets or quasi-poets? Rap isn’t poetry, and shouldn’t try to be; both are capable of great things, but, for the sake of great things, separate ’em! To wit, no matter how decent of a rapper 2Pac was, his poetry is as awful as the inspiration it gave Nikki Giovanni, another bad poet with “Thug Life” tattooed across her forearm, although this excuse is in memoriam. In brief, labeling yourself either does not improve the craft – artists should know better.

That said, rappers do, when they understand the value, purpose, limitations, and opportunities of hip-hop, make good stuff – none of the ‘extra,’ the gimmicks, the bells and whistles of trying to get beyond ‘regular’ hip-hop, and into foreign territory for the hell of it. Moreover, rap judges itself well, if not at first, then a decade or two down the line. All else can be forgotten. It’s why the ‘mixtape projects’ of an early 50 Cent, or the Nobel Prize of a mediocrity like Seamus Heaney, are fruitless – celebrity, and its money, awards, and so on, die with the dead, but real artists endure through their work, not on social crutches. I’ve had people tell me 50 Cent is ‘good’ and ‘original’ because his aggressive marketing got him a record deal, but, out of respect, let’s judge rappers as artists, not telemarketers. It’s a craft which just happens to be a business, not the other way around.

But if like Modenine you claim, beyond celebrity, a paradigm shift, I expect originality, not in context, marketing, or whatever, but in art. Judging these choice snippets (and their musical accompaniment), though —

“Now feel the pain like skinny chicks in labor

Treat it like beer, take it in to get it pissed out”

reminds me of everything else I’ve heard: lyrical competence (even moments of real quality), good performance, nice (if not quaint) production, but that’s it. Moreover, his punchlines are overrated – I can’t imagine playing them for friends, who are used to Ras Kass, Vakill, and other great sources of quotables. Granted, I haven’t heard his earlier work, which I’ve read is better, but “The Paradigm Shift” is mostly a solid effort lacking nuance, depth, or anything truly memorable. Even so, the “Intro,” quoted above, is done over heavy organs and Jus-esque dirt-drums, and hits the sounds pretty well, and with artistic purpose. In brief, the production is slightly better than Modenine’s own contributions, but not by much. No genuinely defining characteristics, either – nothing here distinguishes Modenine from anyone else with talent. “Big Boy Rap” is better, partly from subtlety. It’s loud, epic, and full of violins, played live by Ernest Bisong – lyrically, individual lines are pretty pedestrian, but, against the production, the whispered chorus (“This is big boy rap”), among other things, has substance beyond the obvious – it’s almost ironic and coming-of-age, without dipping to the banal, as sentimental stuff tends to be. If rap can be compared to poetry, it’s these juxtapositions, relationships between different parts, and so on, that make it possible… the comparisons aren’t even linguistic, but structural and emotional, making all references to Wordsworth (or whatever other brand-name – you don’t see rappers aping Wallace Stevens, for good reason) irrelevant. Still, don’t go overboard with the possibilities – not like Modenine has much of this linkage, anyway, except in bursts, like most talented rappers.

Now, on to the bad – fortunately, nothing disgusting or anything, but you’ll get the point. “Your Girl” is not so much full of individual clichés, but something that even otherwise good rappers can’t overcome – narrative clichés, which include too-obvious machinations (or, rather – lack!) of plot, relationships – here, sex, having fun, etc., are all discussed – and so on, complete with moans in the background. It’s pretty unoriginal, and you’d think after LL Cool J’s banal little track was obsolete as soon as LL thought of it, much less recorded, this would not be repeated. But, it is.

“Kick You” has a good use of ‘intervals,’ or silence, in the production, but remains lyrically hidebound. “Follow Your Heart” is the first track of real substance, and deserves a quote:

“One night, I’m at the spot, chillin’ at the back

with this mainstream cat, I feel he’s kinda wack

He said ‘Nine, when you gonna do a party track’

Cut him off, ‘Hammer Time’ was cool, but I ain’t Puff

I pump love when I b-boy, you pump for mass appeal

and still, you don’t even have a record deal

No skill, but you make a little dough so you floss

Catch me at the roundabout, waiting for the bus”

It’s pretty good, but really, just a variation of the same mantra of independent rap: selling out is bad, mass appeal unimportant. A great sentiment, no doubt, but not necessarily executed in an original way, with a soul-ish hook by Eve Urrah undone by the same issue here, as well as in “HipHop,” the following track. Both have that nostalgic feel, which is neutral musically, but, content-wise, too expected for lasting value – nothing differentiates it from better-done alternatives. “Fiyah Burn” features a bunch of very interesting, start-stop flows by African rappers, and “My Skin Is Black” samples Nina Simone, who was once sampled by Talib Kweli in “For Women,” and, unless you enjoy standing in a rather long shadow, shouldn’t really be sampled by most rappers again. Here, it’s completely uninspired, with dull drums over the original’s piano, no real ideas, and a rehash of ‘black themes’ that Talib Kweli at least made vivid, if not a bit trite, a while back. Naturally, it’s better than what most rappers can do, but one shouldn’t settle or compromise on such things.

“Bush Girl, Tush Girl” is almost worthless, save for the electronic ring on repeat, an interesting touch for a ‘love’ song, and a novelty title. I can imagine some great things being done here, with lots of humor and comical production, or even social or philosophical commentary, but nah.

“Forbidden Love” samples Immortal Technique’s sappy “You Never Know,” and basically makes it less interesting. It’s disconnected, and, given the (unmerited) underground reputation of the original, hard to separate the two, or think this addition in any way relevant. By the time you get to “Nine,” you’re pretty tired of his constant, boisterous laughing at whatever witticism he happened to pen that day, but the track is definitely one of the best things here – the violins and keyboards come back, an epic feel, like noted above, that seems to fit Modenine’s cocky style and excellent voice. But, minimalism, like on “Mathematical Sege” works even better, bringing out his voice and encouraging performance – nothing is drowned, and every tone is audible. As a performer, then, he is strongest, and lyrics often come second.

According to Modenine, this is some of the best material in African rap. It’s believable, since I’ve always heard complaints about the lack of idealism in African hip-hop – that is, people there, like artists everywhere, ape the LCD elements of Americana, which is too easy. But Modenine does not, and still remains pretty good without ever touching greatness.