“Canadian rappers rate weak to fair

with the exception of Kardinal, Maestro and Choclair

These eyes seen a lot of ‘Private Symphonies’ fail”

(Pip Skid, “Crantinis at 15,000 ft”, ’01)

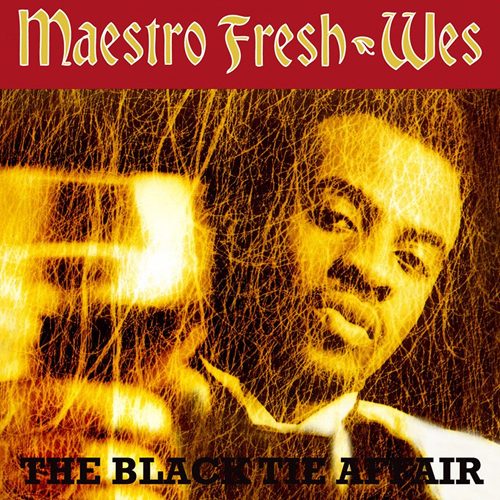

It hasn’t been easy for Canadian MC’s (and likely still isn’t). There is one specimen, however, who made it look incredibly easy some 20 years ago. Maestro Fresh-Wes almost single-handedly created a market for the domestic scene with his hit singles “Drop the Needle” and “Let Your Backbone Slide” and the album “Symphony in Effect” in 1989. His 1991 sophomore effort, “The Black Tie Affair,” was the Maestro’s reaction to the heap of responsibilities the sudden success put on his shoulders. The more urgent of his concerns are summed by the second verse of “Nothin’ at All”:

“My first album, Symphony in Effect, went platinum

In Canada that made me the first black one

to ever reach that goal

I even got offered a movie role

I turned it down, I didn’t wanna be no star

portrayin’ a nigga that dwells behind bars

They wanted me to act like a prisoner

That ain’t positive at all, it’s just givin’ a

negative image of a black man, forget it

LTD, what did I tell em? (I ain’t with it)

I rather work on my sound and stay down

I move and groove with the underground

God gave me the gift to write

I shed light on the blind with a rhyme when I recite

A fresh poem, a page on a stage, or a story of glory

– not derogatory

I never walk the streets with my nose high

frontin’ like I’m so fly, I never post high

Why, cause I made a little money?

I’m still viewed as a s-l-a-v-e, see

It doesn’t matter how good you can rap, jack

It doesn’t matter how much money you stack – cause you’re black

Without knowledge of self you’re trapped

and gonna fall

with nothin’ at all”

As a now certified rap star, Maestro Fresh-Wes saw it as his obligation to be a role model. And he made sure to mention others who he felt could serve as an inspiration even when greater society sometimes failed to acknowledge their achievements. “Nothin’ at All” mentions resident artists and athletes such as Lennox Lewis, Oscar Peterson, Salome Bey, and particularly boxer Egerton Marcus, silver medallist for Canada in Seoul and of Guyanese heritage like Wes himself:

“Third verse, how should I start this?

I talk about my homie Egerton Marcus

a brother from Toronto who’s goddamn great

Olympic middleweight champ in ’88

He excelled to the second heighest level

in Korea, bringin’ home a silver medal

Made the papers for a couple of days and that was it

Huh, the media was sayin’ shit

To keep it short and keep it simple and plain:

If Egerton was white he’d be a household name

with commercials and endorsements like Shawn O’Sullivan

Livin’ large and everybody would be lovin’ him

Well, he’s my brother, so I give him recognition

I sell a lotta records, so the kids are gonna listen”

“Nothin’ at All” is both accusatory and motivational, gospel singer George Banton providing the lamenting chorus while the rapper touches on everything from ‘race scientist’ Jean-Philippe Rushton to Canada’s policy on its indigenous people. He even goes as far as taking the side of sprinter Ben Johnson, the era’s most infamous doping offender. The pro-black stance is a prominent mark of several other tracks. “Poetry Is Black” is a whirlwind of a rap track, as Wes projects his militant literal theory over a tribal beat, drawing a straight line from his raps back to the motherland:

“Cause that’s where the beat of the drums originated

I hope that you’re updated and educated

And from the dum-drums then came the rhythm

In 1991, my son, that’s how I’m livin’

And from the rhythm then came the raps

Now I’m pumpin’ out tracks on wax, poetry is black”

He exudes optimism at a more accomodating pace on “Watchin’ Zeros Grow” – still aware of the prejudices that might hold him back: “Some people think blacks should not be vocal / they want us to shut the hell up and stay local / be contented with what you have and / forget about the serious songs and stick to braggin’.” The title track again touches on themes of Afrocentricity, self-destruction, and media stereotyping. None of this is exceptional for 1991. In fact, one could accuse Maestro Fresh-Wes of following the lead of US rappers too closely. Yet keeping in mind the unique position Wes found himself in, the new political direction makes sense. Given that background, the transition from “Symphony in Effect” to “The Black Tie Affair” seems more natural than let’s say between King Sun’s first two albums, to use the example of a rapper representing the very birthplace of hip-hop, the Bronx.

On a lighter note, here are some of the things that changed with “Symphony in Effect”: “Toronto was a virgin, but it ain’t no more / Maestro popped the cherry, now it rocks hardcore.” He “opened the doors for both you and your mother.” And “all the girls who used to diss the Maes / say: ‘Shit, I could have been like Ice-T’s wife / on the cover of the albums, with gold medallions’ / But you blew it, so take a valium.”

Stylistically, Maestro Fresh-Wes belongs to the Big Daddy Kane school of emceeing. He’s a charmer to the ladies, a benefactor to society, an entertainer to the audience, and a threat to foes. Clearly bred on battling, Fresh-Wes isn’t afraid to hurt feelings, cutting recklessly across the one-verse opener “On the Jazz Tip,” or playing bouncer with guest K-4CE on “VIP’s Only.” “The Maestro Zone” is another hip-hop hurricane doing damage:

“So let the Fresh lead, here for the next breed

Critiquin’ like Rex Reed, makin’ your text bleed

Ruder than Rick Rude I made a intrude

Niggas sweatin’ bullets, shittin’ bricks and pissin’ ice cubes

Unprofessional, easily detectable

Spectacles are glued to my testicles

Movin’ round like a bunch of homosexuals

I turn fruits into vegetables

Breakin’ bones on the microphone

You’re in the Maestro Zone”

The downside of Stro’s dense lyrical performance are the recurring ’88 era internal rhymes. Rap references to Shakespeare rarely do justice to the man’s standing, but “Tax, wax and break and shake like Shakespeare” probably qualifies as the most nonsensical ever. In that particular regard Maes was definitely old school by 1991 standards. But when it came to throwing punches, this Canuck could easily spar with the Yanks: “Because I’m from Canada don’t think I’m a amateur / cause I’m so fly I’m droppin’ dope like Panama / Last year I wore a black tuxedo / now chicks pay to see me in my silk black Speedos.”

The best thing about “The Black Tie Affair,” however, might be the musical adaption of its MC’s ‘classical’ shtick. While the professionalized remix of quiet stormer “Private Symphony” is cliché R&B, the rest of the production is hardcore hip-hop with a subtle swing vibe to it. Three tracks are handled by Wes and the team from his first album, First Offence Productions. They put together the functionally thoughtful “Watchin’ Zeros Grow” and “Nothin’ at All” and the closing after-show cypher “Pass the Champagne.” Which leaves seven tracks for K-Cut, best known for (together with Sir Scratch) making up the Toronto branch of Main Source, who under the lead of Large Professor released the hip-hop classic “Breaking Atoms,” coincidentially also in 1991.

“Conductin’ Thangs” steers smoothly across the dancefloor, deriving its shuffle from the Skatalites song BDP used for “Edutainment.” “On the Jazz Tip” has pianos that bang almost as hard as the drums. “Poetry Is Black”‘s pumping rhythm is virtually made to pump your fist to. “The Black Tie Affair” is a modestly playful beat with prominent cutting and a late pattern change. “VIP’s Only” is as pugilistic as boom bap gets with steam-rolling drums and funky highlights in the hook. “LTD Makes a Toast” has DJ LTD going against horn flares and dense drums. “The Maestro Zone” might just feature the most flavorful horns in hip-hop ever. And then there are two excellent (uncredited) interludes at the end of the album that could also very well have been produced by K-Cut. Bottomline, his beats here rival almost anything DITC put out in the early ’90s and notorious nostalgists would probably be all over them if they were produced by some big name East Coast producer like Pete Rock or Large Professor.

“Symphony in Effect was just a mic check,” Maes boasted on the album’s lead single. “The Black Tie Affair” was clearly a more professional record, even as it lacked dancefloor favorites. Sales-wise, however, it went gold, not exactly the next level after a platinum debut. 1991 was nevertheless a highly successful year for the Toronto MC as he won two Juno awards (with three additional nominations), one for Best Video (“Drop the Needle”), one for Rap Recording of the Year (“Symphony in Effect”), the latter being the first ever issued by the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences in that category. In an effort to cross the border, the album was re-packaged in 1992 as “Maestro Zone,” minus “The Black Tie Affair” and three interludes and with an abridged version of “Watchin’ Zeros Grow.” Four songs were added, notably the production-themed “Another Funky Break (From My Pap’s Crate)” and the lewd but funny “Hittin’ the Girlschools.”

On “The Black Tie Affair” Maestro Fresh-Wes is conscious in the very sense of the word – conscious of the fact that what he says and does has an impact on his audience. The result is an album that reflects both the era’s climate and the rapper’s personal situation. “Facts I holler and still make dollars,” he rhymed, convinced that he could pull it off. It’s that conviction and the confidence with which it is brought forth that make this album an important Canadian release that should even at this point find fans anywhere in the world.