Folklorist and musicologist Alan Lomax spent his professional life researching, recording, and archiving traditional music. On his travels he also met blues singer Blind Willie McTell, who he taped for the Folk Song Archive of the Library of Congress in 1940. In a segment available on Blind Willie McTell releases entitled “Monologue on Accidents,” they engage in a conversation in which the interviewer tries to extract from his subject if he knows “any songs about colored people having hard times here in the South.” McTell declines. Lomax insists, “You don’t know any complaining songs at all? ‘Ain’t it hard to be a nigger, nigger’ – do you know that one?” 42-year-old Blind Willie brings up “a spiritual down here, It’s a Mean World to Live In,” which according to him “has reference to everybody.” Lomax instigates, “It’s as mean for the whites as it is for the blacks, is that it?” To which McTell replies, “That’s the idea.” He’s then suddenly probed, “You keep moving around like you’re uncomfortable, what’s the matter, Willie?” He responds by mentioning “an automobile accident last night” which left him a “little shook up” and “still sore probably.” The recording ends with a brief “Hmm” by Lomax.

Lomax’ preservation work was deservedly honored and is of great historical significance. There is, however, often something awkward about an anthropological encounter as the one documented above (further factoring in that Lomax could have confused McTell with Blind Willie Johnson), and this awkwardness extends generally to the last century’s interest in ‘authentic’ folk music, in this case country blues. Comedians Cheech and Chong recorded a ’70s routine which includes what could very well be a Lomax parody approaching a terrible stereotype of a blues singer named Blind Melon Chitlin’, “Listen now Blind baby, what we wanna go for on this record is not just a blues record, but we want a document. A epic document depicting the struggle of the black people against the white devil slavemasters. You got that?”

That last soundbite pops up on Da Lench Mob’s “Guerillas in Tha Mist” album, in the song “Ankle Blues.” In 1940, when segregation was still in full effect, Blind Willie McTell was naturally reluctant to admit that he knows any ‘complaining songs’ that could be construed as having political content. Not so Da Lench Mob in 1992. They knew an entire album of ‘complaining songs,’ and they wrote them all themselves. Opposite a white man with an official mandate, Blind Willie had no other option but to deny any knowledge of current songs “complaining about the hard times and sometimes mistreatment of the whites.” “No sir, I haven’t. Not at the present time, because the white people is mighty good to the southern people, as far as I know,” he offered.

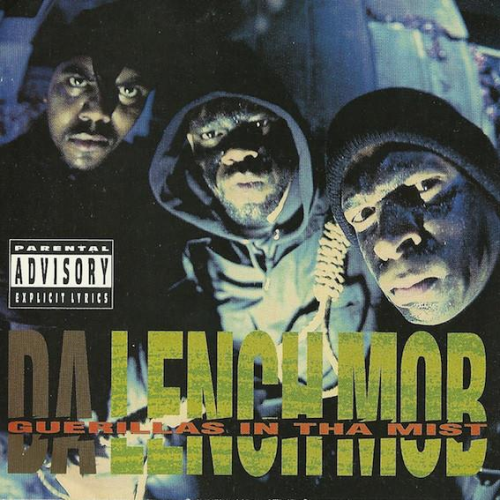

Da Lench Mob on the other hand were expected to speak up, and on their debut album they went far beyond simple ‘complaining songs.’ Originally a name for Ice Cube’s post-N.W.A posse at the start of the ’90s, Da Lench Mob rather unexpectedly became a full-fledged rap act. Consisting of J-Dee, Shorty and T-Bone and featuring Cube himself as an inofficial fourth member, Da Lench Mob recorded an incendiary album that in its very own way documented how things had heated up. In 1986, a mere six years before, “Guerillas in Tha Mist” would have been inconceivable. The closest thing to it would have been Run-D.M.C.’s “Proud to Be Black”, and even that is far from what J-Dee and company have to say. By 1992, though, a record like “Guerillas in Tha Mist” simply followed the natural course of events.

This is where we have to place the disclaimer that RapReviews.com does not condone racism in any way, shape, or form. At the same time this critic is ready to admit that he is liable to enthusiastically rap along to extended parts of this record. Hate music in my limited experience is also bad music. Poorly executed, dumb, dull, betraying the stupidity of the involved musicians. But I won’t rule out the possibility that someone who is familiar with the greater genre of rock will attest some hate rock a certain proficiency. Because that’s what I find myself doing now in the case of rap. ’90s rap was known to cross the line from pro-black to anti-white on occasions, and just as often such statements and sentiments were swept under the rugs of tolerance and guilt.

A RapReviewer of a certain age is prone to excuse and explain a record like “Guerillas in Tha Mist.” One explanation would be that it is a revenge fantasy, a set-up frequently seen in Hollywood. Basically anything in the genres of horror, fantasy, western, action, sci-fi, comedy that works with the premise that a former or potential victim suddenly gets the upper hand. The past year alone has seen several World War II plots (‘Defiance,’ ‘Valkyrie,’ ‘Inglorious Basterds’) where Nazis get their just desserts. Of course Nazis are easily identifiable as the bad guys, that’s why neo-Nazi hate music has a hard time rallying sympathies, as much as its exponents try to paint themselves as underdogs who suffer under the alleged dominance of non-whites.

“Guerillas in Tha Mist” inherently argues that blacks so far have been on the receiving end of the stick. That they were in fact the ones who were chased by lynch mobs. The album opens with a truly gruesome intro entitled “Capital Punishment in America,” where a narrator gives a run-down of the subject at hand while tortured souls scream in the background. The retribution immediately kicks in with “Buck tha Devil,” which introduces us not only to the term white people generally go by on this album, but also what Da Lench Mob would like to do to them. As far as rap music influenced by black supremacists goes, “Guerillas in Tha Mist” is the one that most actively adopts their most aggressive tone. If memory serves, all three Lench Mobsters were registered Nation of Islam members. The NOI is mentioned several times. At one point the race war games even get a spiritual spin: “Armageddeon is a confrontation / that’s the information comin’ from the Nation.”

Their weapon of choice is announced by “Freedom Got an AK.” “I wish y’all was in Dixie / AK, AK / and shit wouldn’ta been bad in the ’60s / No way, no way,” they chant, making it abundantly clear that they do not believe in peaceful protest – “cause this week we don’t turn the other cheek.” Instead it’s an eye for an eye, and on top of that a plea for equal opportunity when it comes to the Second Ammendment:

“Cause the AK-40-dick hold a 50 clip

and I’ll shoot till it’s empty, bitch

That’s how you got filthy rich

I know the game, so I’ma do the same

Don’t like when I play the same way

and say: Hey, freedom got an AK”

Firearms already being in the hands of drug dealers and gang members, Da Lench Mob argued for them to be put to ‘proper’ use. At least that’s the underlying message of “Who Ya Gonna Shoot Wit That”: “Who you gon’ shoot with that, homie? (…) Why does your gun say ‘Niggas only’? / But you need to get a angle on a Anglo / I mean shoot your bucks at the Ku-Klux.” Eventually fratricide is committed by J-Dee himself at the end of the song, which at least is congruent with “All on My Nut Sac,” which finds him bumping heads with a local pusher who also ends up dead. And there is the case of the kid who takes down his crackhead mother in “Ain’t Got No Class.”

“Guerillas in Tha Mist” has a clear agenda. It purposely looks at the world in black and white. Even “Lost in Tha System,” where J-Dee is swallowed by the prison-industrial complex simply for failing to pay a ticket, can’t do without black-on-white violence:

“Gone to the hole again

for shankin’ a devil with my motherfuckin’ ink pen

Things gettin’ kinda rough and disturbin’

They takin’ me to court for this motherfuckin’ servin’

Since I’m black and I’m supposed to be wrong

the prosecution wasn’t very long

Start stackin’ months on me like hot cakes

and in the morning I was headed upstate

for shankin’ a fool who’ll never be my brother

the simple fact the motherfucker had the wrong skin color

Yo, I told the judge, ‘Don’t even try it’

He gave me a year for startin’ a riot

I told this old-ass fool, ‘Suck my dick

givin’ me a year for this shit!’

Yo, he added on another year, cause I dissed him

Now here I go gettin’ lost in the system”

If it wasn’t for the First Ammendment, “Guerillas in Tha Mist” would have been one of the few (or maybe one of the many) rap albums to be censored or banned, that is for sure. One specific word is bleeped, but it stands to argue what is worse, calling Washington a “faggot” or applauding that “Lincoln got bucked in the face.” “Fuck You and Your Heroes” is probably the album’s quote unquote most controversial song, completely over-the-top but, if you agree that Da Lench Mob have any kind of case here, an interesting and entertaining mud-slinging at some American darlings:

“(Madonna, you motherfuckin’ slut

you can show your butt and jimmy still won’t get up)

The Beatles – I just can’t fade

Get the motherfuckin’ Raid, Bone, we got roaches

And Fonzie can’t rumble

And by the way, you can have Bryant Gumbel

Babe Ruth was good against the white boys

but he couldn’t hit a nigga like Doc Gooden

Marylin Monroe was a ho for the Kennedy’s

Don’t worry, J-Dee know the enemies

(…)

Don’t talk about Bird and all of his scorin’

cause I’ll say Magic, Ewing, Jordan

Olajuwon, Isiah and Barkley

(Now bitch don’t start me)

(You ask me did I like Arsenio?)

Cube, tell ’em (Motherfucker, no!)

Take it from Da Lench Mob

Elvis is dead as a doorknob

Never been caught for all the songs he stole

(And you put James Brown on parole?)

I know the deal, you hate to see a black face

(win the motherfuckin’ race)

Cause you still think we’re negroes

But I say – fuck you and your heroes!”

“Guerillas in Tha Mist” is a rich mix of political and pop cultural references. The album title exceeds simple wordplay as it sets the stage for the South Central collective posing as gorillas, only that they have decided to take matters into their own hands and become guerillas, rather than wait for some white chick to rally international attention to their plight (as zoologist Dian Fossey did in her autobiography ‘Gorillas in the Mist,’ which was turned into a hugely successful movie starring Sigourney Weaver in ’88). Da Lench Mob took the idea of ‘black power’ to a whole ‘nother level. The video accompanying the title track was an adaption of ‘Predator,’ but the compelling imagery lied in the lyrics. They touch on everything from colonial leftovers to present day phenomenons (“Lench Mob environmental terrorists”), alternating between plain guntalk and extended Tarzan analogies:

“Finally caught up with a devil named Tarzan

swingin’ on a vine, suckin’ on a piece of swine

Jiggaboo come up from behind

Hit him with a coconut, stab him in his gut

push him out the tree, he falls right on his nuts

And just like EPMD

I don’t like a bitch named J to the a to the n-e

Can’t wait to meet her, I’m gonna kill her

cause that little motherfuckin’ Cheeta can’t hang with a gorilla”

One can argue that Jane and chimpanzee Cheeta are definitely not the same character in the Tarzan franchise, but the link to EPMD’s Jane is pure genius from a rap connaisseur’s point of view, as is the idea of the Lord of the Jungle “suckin’ on a piece of swine” while “swingin’ on a vine.” It may be difficult to relate to all of this without reflecting on what Tarzan stands for and being familiar with Nation of Islam and Five Percenter rhetoric. None of the lyricism in “Guerillas in Tha Mist” is great literature, but the rhymes often form a compelling web of references that is most alluring when the entire group performs, Cube, Shorty, and even T-Bone supporting lead vocalist J-Dee with great precision.

Da Lench Mob bottle up a furious mixture of racist demagogy and righteous indignation, minstrelsy turned on its head, hand-picked pop culture clichés – shake it and let it explode in your face. Imagine Paris and X Clan’s Brother J joining the Jungle Brothers to fuse Public Enemy and N.W.A. Like all emancipatory art, it turned (perceived) weakness into (alleged) strength. And it employed comedy: “White boys like Godzilla / But my super nigga named King Kong / played his ass like ping pong.” In short, racism never sounded so catchy. Does that make it twice as or half as dangerous? Fact is that for someone like me with a clear bias for rap music, “Guerillas in Tha Mist” does a lot to endear itself to me while it tries its best to alienate me as a white person.

Blind Willie McTell was right. It is a mean world to live in, often an outrageously mean world. Fighting fire with fire, Da Lench Mob do little to make it less mean. If you have to attest a rap album that it isn’t explicitly anti-Semitic on top of everything else, that’s a sad commentary. “Guerillas in Tha Mist” stooped to unprecedented lows and simultaneously rose to unexpected highs. The production by Ice Cube, T-Bone, Rashad Coes, Mr. Woody, and Chilly Chill is spot-on, a cross between “AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted” and “Death Certificate” with a strong dose of “Cypress Hill.” “All on My Nut Sac” features J-Dee and Cube in one of the most refined rap duets of the ’90s. The title track might be one of the most brilliantly realized concept tracks in history. The two Shorty solo tracks, deliberate tributes to the blues and the gospel, create a crucial counterbalance to the preceeding mayhem. (In “Ankle Blues,” the payback turns out to be only a dream, while the Cube-penned “Lord Have Mercy” is up there with his best reflective material.) What first appeared to be an artificial concept group, can now be regarded as one of hip-hop’s best group projects closely affiliated with an established rapper. As much Ice Cube is in this album, it also contains very real blood, sweat, and tears.

“Guerillas in Tha Mist” went gold in December ’92, a few days after the release of an album that soon came to overshadow the rest of contemporary West Coast rap, Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic.” Unlike “The Chronic” and Cube’s own December release, “The Predator,” “Guerillas in Tha Mist” was not recorded under the impression of the April ’92 events following the Rodney King trial. It didn’t need that explicit reason to be that angry. (It is safe to speculate that while it was recorded before April, it was deemed so explosive once LA erupted that its release was pushed back.) Lord Jamar once lamented fellow blacks who “do the work of the Klan.” There’s been an abundance of rap records that portrayed (if not downright promoted) such behavior. Da Lench Mob, as trigger-happy as any gangsta rap henchmen, take the other side, opposite the KKK. That they don’t turn the other cheek but instead aim for the other’s eye may be morally reprehensible, but also creates a thrilling piece of music.