I first heard Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” about twenty years ago. I couldn’t believe what I was hearing: he sinister bassline and funky drumbeat were clearly a product of the 70s, but the Scott-Heron’s vocals sounded like Chuck D.

“You will not be able to stay home, brother

You will not be able to plug in, turn on and cop out

You will not be able to lose yourself on skag and

Skip out for beer during commercials

Because the revolution will not be televised”

The song was both a call to action and an indictment of the twin opiates of television and consumerism. Scott-Heron took jabs at political figures of the day and popular ad campaigns. Revolution was imminent; in light of that, everything else seemed trivial. Whether or not he knew it, Scott-Heron was rapping, about four years before hip hop was created and rap actually became a form of music (and over ten years before rappers would consider rapping about anything so serious). The song has been referenced by countless rappers, including Common, Public Enemy, Aesop Rock, Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, and the Wu-Tang Clan. The phrase has also been borrowed a million times over, most recently in reference to the protests in Iran, but also by filmakers, journalists, and even ad campaigns. No matter how many people try to co-opt the song, it still retains its power, forty years later. It’s a great proto-rap song, and a great song period.

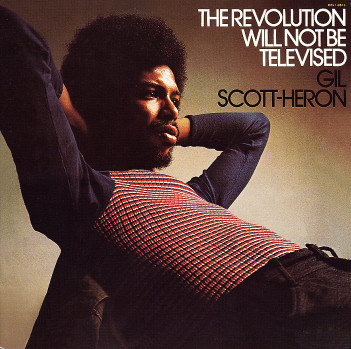

The song originated as a poem spoken over bongo drums on Scott-Heron’s 1970 debut, “Small Talk at 125th & Lenox”. Like the Last Poets, most of Scott-Heron’s early work was basically poems chanted over drums. On his 1971 follow-up album, the essential “Pieces of A Man,” Scott-Heron added a full band, including his friend and collaborator Brian Jackson on piano and the stellar Bernard “Pretty” Purdie on drums. All of “Pieces of A Man” is collected in the 1974 compilation “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” as well as tracks from his debut album and 1972’s “Free Will.”

Scott-Heron the poet/proto-rapper is represented on tracks like “No Knock.” Over a drum beat, Scott-Heron criticizes attorney general’s John Mitchell’s new policy of not requiring police to knock on doors before entering. Scott-Heron’s anger is palpable as he describes the abuses of the policy:

“No knocked on my brother Fred Hampton

Bullet holes all over the place

No knocked on my brother Michael Harris

And jammed a shotgun against his skull

For my protection?

Who’s gonna protect me from you?

The likes of you?

The nerve of you?

Your tomato face deadpan

Your dead hands ending another freedom fan

No knockin’, head rockin’, inter-shockin’

Shootin’, cussin’, killin’, cryin’, lyin’

And bein’ white”

If that last part sounds familiar, it’s because Common paid homage to it on “Universal Mind Control.” Scott-Heron takes on Black radicals on “Brother,” discusses “Sex Education – Ghetto Style,” and on “Whitey On the Moon” juxtaposes the squalor and poverty of the ghetto with all of the money being spent on the space program. “I think I’ll send these doctor bills air mail special to whitey on the moon,” he raps over a drum beat.

There’s another side to Gil Scott-Heron besides fiery militant poet. He has a beautiful voice, which he uses to great effect to chronicle the perils and sadness of inner-city life on songs like “Save the Children,” “The Needle’s Eye,” and “Did You Hear What They Said?” One of his most heartbreaking songs is “Pieces of A Man.” Over a sparse bass and piano interplay, Scott-Heron describes a boy watching his father fall apart after being laid off. “They didn’t know what they were doing/they could hardly understand,” he sings. “That they were only arresting/pieces of a man.” It’s absolutely devastating.

It’s not all gloom and revolution, though. He has his upbeat moments as well. “Lady Day and John Coltrane” is about the way the music of jazz icons Billie Holiday and John Coltrane “wash your troubles away.” “I Think I’ll Call It Morning” is a positive song about concentrating on the good things in life. “When You Are Who You Are” criticizes a woman for not being true to herself, telling her “you could be so very beautiful/when you are who you are.” These songs are all uptempo, early 70s jazz that feature intricate drumming and breezy saxophone.

Drugs are also a recurring theme on the album. Scott-Heron has battled addiction for decades, and has spent most of the last twenty years either in treatment or in jail for drugs. He’s most explicit on “Home Is Where the Hatred Is” calling himself “a junkie walking through twilight,” and explaining that:

“Home is where I live inside my white powder dreams

Home was once an empty vacuum that’s filled now with my silent screams

Home is where the needle marks

Try to heal my broken heart

And it might not be such a bad idea if I never went home again”

Scott-Heron’s honesty about his failings makes him a much more complicated and interesting artist. In an interview in ChickenBones, he complained that rappers “use a lot of slang and colloquialisms, and you don’t really see inside the person. Instead, you just get a lot of posturing.” In contrast, he’s never afraid to lay himself out. On “Or Down You Fall” he tells a lover:

“Go away

I can’t stand to see your face

Cause you’ve seen the weakest me

And now you know I’m only human

Instead of all the things I’d like to be”

While I originally bought “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” because of the title track, songs like “Or Down You Fall” and “Home Is Where the Hatred Is” are the reason I keep listening to it, twenty years later. Gil Scott-Heron is an amazing lyricist, an excellent singer, and he is backed by some very skilled musicians. “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” is funky, inspiring, and a must-own for any hip hop head interested in exploring the roots of rap.