“This is not for commercial usage

Please don’t categorize this as music

Please don’t compare me to other rappers

compare me to trappers

I’m more Frank Lucas than Ludacris”

(Jay-Z, “No Hook,” ’07)

A few years ago you could spot rap celebrities rocking t-shirts that said I’M NOT A RAPPER on the front and JUST A HUSTLER THAT CAN RAP GOOD on the back (for instance The Game in an episode of MTV’s ‘Punk’d’). Now as a rap fan I have supported many a hustler that can rap good, and I stand behind every single purchase. I’m also a sucker for rhetoric and am appreciative of rappers who try to set themselves apart from others by calling themselves this and that. It’s all part of the game. When the Bay Area’s J-Diggs rhymes: “I’m really not a rapper, I’m real, real street with it / all I did was take my life and mix a little beat with it,” I find those types of sophistries kind of clever.

What I’m uncomfortable with is the anti-rap climate created by some of these hustlers that apparently just happen to rap. As XXL blogger Tara Henley wrote some years ago: I think 2006 will be remembered as the year that The Hustler trumped The MC as the prevailing icon of the culture. The year that rappers became so busy trying to be entrepreneurs and pitchmen and Hollywood actors that they didn’t have the time or the inclination to make dope music anymore. The year that being a rap artist — someone who sincerely aspires to spit mind-blowing rhymes — became, well, kinda corny. The year all your favorite rap stars started adamantly denying they were rappers. Where, exactly, does that leave rap fans? If it’s corny to make rap music, is it corny to listen to it too?

Rakim, one of history’s most universally recognized rappers, told The Source back in 1997: “A lot of the media right now don’t consider most of us as artists. They feel we just rappers or hoodlums from the streets that’s rappin’ now”. If rappers nowadays even recject the notion that they’re just rappers and content themselves with being hoodlums from the streets that’s rappin’ now, the artform’s future is indeed bleak, regardless of the changes in its customership.

The aforementioned shirt merely provided the ideology with a slogan, and it would be unfair to put The Game on blast, who exposes himself as a rap fan in many of his songs. There are enough others who denied rap at some point. The Clipse’s Pusha T most memorably, when he indignantly declared, “I’m not you, rapper.” Jay-Z and his man Beanie Sigel have been on the forefront of denying rap, which is especially bewildering in the case of the former, who has been trying to get on since the mid-’80s. To rate the hustler higher than the rapper means putting economics over artistry like any greedy record label. It is disrespectful to those who managed to turn rap into an artform to begin with.

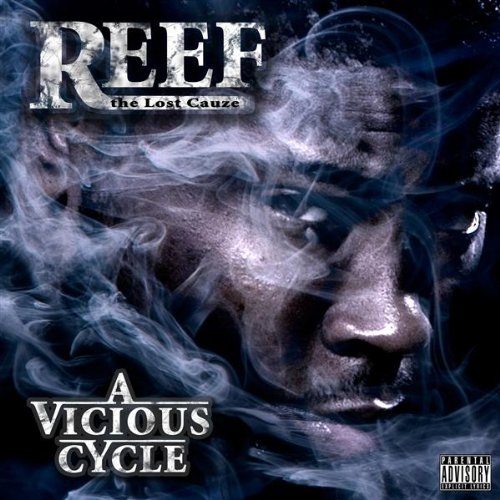

Despite having pondered this before (the above introduction was intially meant for a JT the Bigga Figga review), Philadelphia’s Reef the Lost Cauze caught me off guard with a song on his latest album entitled “I Ain’t No Rapper.” Having proven to be a highly competent songwriter, he now leaves “I Ain’t No Rapper” wide open to misunderstanding. The problem is the hook, which goes as follows: “I’ma end up in all y’all top 10 / like G Rap, Big Daddy and Rakim / Biggie and Pac… Yo, who shot them? / I don’t really give a fuck – I ain’t no rapper!” When you delve a little deeper into the issue it becomes evident that Reef respects rap highly. The most logical interpretation is that he’s serious about the first three lines and then mocks non-rappers with the last one. If you reject being called a rapper, why should you care who killed two of the greatest, why should you care about being ranked amongst the greatest? Unfortunately for Reef the hook itself will remain mystifying to casual listeners, and the content of the verses does very, very little to enlighten them while the KRS-One intro which puts The MC over The Rapper adds yet another, completely unnecessary context. In the end Jay-Z keeps the upper hand in this imaginary debate between Hustler and Rapper because he also prevails at rap. (This reviewer rates “American Gangster” as one of the finest moments in modern day hip-hop.)

So what else was on Reef’s mind in 2008 and how well does it translate to “A Vicious Cycle”? At a full 18 tracks, it seems he was going for what he considers a well-rounded album. The desire to reach the next plateau is eminent as he quotes LL Cool J and 50 Cent in their heyday. “I Wonder” is reminiscent of Jadakiss’ graduation speech “Why.” The closing “Still I Rise” should ring a bell with most ’90s rap fans, as that was the title of one of the earlier posthumous 2Pac albums. And let’s not forget the impressive CD booklet where several songs are illustrated by scenic pictures from M. Scott Whitson.

Both “Still I Rise” and “I Wonder” have considerable mass appeal, one maybe on a more mainstream level with its optimistic acoustic guitar and female hook, the other in traditional hip-hop circles who can appreciate Marco Polo’s epic beat and Reef’s mature reflections. They should also be able to relate to conceptual joints such as “Gone” and “Amnesia,” which both tackle familiar topics from unusual angles. More standard are “When You Get Free” and “Home,” addressing locked up homie and fam, respectively. And just when you think he should leave descriptions of debauchery to AZ or Kool G Rap, “Thug Fantasy” takes an interesting twist. Finally we have the ambitious songs dealing with social and political issues. Set to an almost rural beat by The Unknown Soldier, “Nat Turner” aspires to tell the story of the slave revolt. “Bad Lieutenant,” inspired by the movie of the same name and Nas’ “Shootouts,” is a corrupt cop’s account of how he controls his beat.

Lyrically the Army of the Pharaohs member lets loose on he HBO-inspired “Pay-Per-View,” the Sharon Jones-sampling “I Ain’t No Rapper” and “Big Deal” (whose single remix features an excellent Brother Ali guest appearance). Maybe Reef’s range is best summed up in the album’s first verse, set to the swerving piano and heavy cutting of “Back at It”:

“Aiyo, it’s Reef the Lost Cauze, whoopdediwoo

Half man, half animal, Zoobilee Zoo

People often stop me when I’m manoeuverin’ through

Sayin’, ‘Hold it down for Philly like you usually do’

I reply: Ya damn skippy, I am 50

before he got shot, these pussies just can’t hit me

I’m the equivalence of ridiculous

You know who I am, you are all witnesses

The son of Jarell with a gun and a l

From where the winters is cold and the summers is hell

Old vultures and young birds with somethin’ to sell

if not, waitin’ to rob you under the L

Dear America, you motherfuckers have failed

cause a nigga either die in the street or suffer in jail

There’s no in-between, unless you gettin’ green

Ain’t no inheritance from my heritage, so by any means

Reef is back”

As far as the club tracks go, a hip-hop fan is always inclined to dismiss the ones that seem to fail their purpose by not gaining entrance into actual clubs (the same goes for radio tracks without actual airplay). Last time around, this reviewer was hoping “Look at the Sun” would get some spins, but now wouldn’t personally select “Not That Easy” or “Listen to Me,” the latter a sinister affair laced with G-Unit flows, the former perhaps lyrically superior to your average dancefloor filler but musically sub-par.

There is a certain breed of rappers that always have to prove themselves – to fans, to critics, and often most of all to themselves. In fact the need to be validated is so common in rap that those artists that do not feel they have to prove themselves are the exception from the rule. With “A Vicious Cycle,” the Lost Cauze is out to prove that he’s a complete artist who has “mastered every aspect of the game like Tim Duncan”. He wants to be “the gap between Big Daddy Kane and Young Jeezy,” a hustling and hungry Fiddy, a triumphantly returning Cool J circa 1990. In reality he has yet to break through to the masses of rap fans. The fact that this review comes more than half a year after the release date is telling. Reef may still be a hustling rapper, one thing he is not – a rapping hustler. It is therefore expected that he excels at emceeing, which ever so often he does with his elevated gift of gab. Some tracks here prove to be dead ends, but with some serious songwriting skills and solid production (most notably from longtime collaborator Eyego/Direct), Reef avoids setting himself up for failure. Compare him to other rappers – in the long run possibly even the greatest of ’em.