RapReview readers may be wondering why I’m reviewing a dub reggae album on a hip hop site, much less a dub reggae album that is out of print and impossible to find legally. Don’t blame me, blame Jeff Chang, Bill Brewster, and Frank Broughton. Chang credits dub as one of the ancestors of hip hop in his essential history of hip hop, “Can’t Stop Won’t Stop,” and Brewster and Broughton describe how the sound of dub became a template for hip hop in their book “Last Night A DJ Saved My Life: The History of the Disc Jockey.” I had always thought of dub as the even more boring cousin of reggae, and had little interest in it. Chang, Brewster, and Broughton brought me around.

For those of you not familiar with dub, it is basically remixes and reworkings of songs, hence the term “dub” for double or copy. Dub typically removes or downplays the vocals, and buries the instruments under layers of effects, reverb, and studio magic. Dub songs will often isolate the bass and/or drum, stripping the track down to its bare essential riddim. Dub started out as B-side “versions” of existing songs that would be played over sound systems. Deejays would toast over these instrumental tracks, which became a blueprint for hip hop that Jamaican transplant Kool Herc brought to the South Bronx. If live dub was the blueprint for hip hop, dub in the studio was the blueprint for hip hop production, because it essentially involved manipulating an existing song to create something entirely new. Dub producers play with reggae songs in a similar way to how hip hop producers cut up old soul and funk records to create hip hop beats.

Besides being an instrumental version of vocal reggae tracks, dub is also often a darker take on the music. There is a sinister edge to the brooding bass and echoing guitars in dub. If reggae is the equivalent of drinking beer in the sun, dub is that moment around three in the morning when the booze is wearing off and the world looks strange and unfriendly. If reggae is smoking nice herb with friends, dub is the shady dealer who is trafficking in good times but packing heat. There’s not much “One Love” brotherhood in dub’s heavily reverbed sound. It was born during the violence that engulfed Jamaica in the 70s, and references a side of the island that the tourists don’t see, the political turmoil, the street violence, the corrupt police.

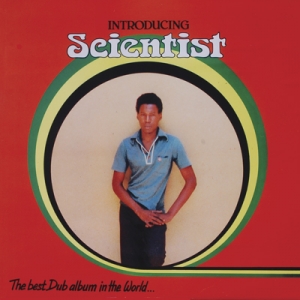

Hopeton Brown, aka Scientist, was born in Kingston, Jamaica, and was a disciple of dub pioneer King Tubby in the 1970s. The modestly titled “Best Dub Album In the World” was Scientist’s 1980 debut. Listening to Scientist, I immediately saw a connection to hip hop. In the same way that a hip hop producer will tweak the elements of a song into something totally new, Scientist isolates the instruments in each song, deconstructs them, and then spins them back together into a unique beast. The eleven tracks here are centered around the riddim, the pulsing bass and drums. Any melody is incidental, added sparsely and then manipulated until it is unrecognizable. Take “Scientific.” It starts off with a familiar sounding keyboard melody, then removes it so that all is left is the bass and echoing snare snaps. Then he adds in hints of the melody, a little guitar, a little organ. It’s just enough to give you the idea of a song, but never quite giving you satisfaction. It’s almost like a dream version of the song; it alludes to the original, but remains unfamiliar and unsettling.

Most of the songs follow the pattern of “Scientific.” They start with a melody, which drops out, replaced by the bass and drum. The melody is then slowly reworked back into the track, but never completely. It’s a trippy, druggy, disorienting sensation, equal parts awesome and unnerving. As someone who was never into the more feel-good aspects of reggae, the sinister vibe of this album works perfectly with my natural cynicism. It reminded me of Madlib and MF DOOM’s production work: sparse, trippy, and a little menacing. In fact, this feels more like an instrumental hip hop album than a reggae album. None of the songs clock in at longer than three minutes, and there is a sense of experimentation and messing with the source material that I associate more with hip hop than reggae.

I don’t know if Scientist’s debut is truly the best dub album in the world. I stumbled across it by searching for “best dub album” on Google. (It may impossible to find legally anymore, but there are hundreds of dub fans who are willing to share their copy with you.) What I do know is that it is an excellent introduction to the genre, especially for listeners who are dubious of reggae’s sunsplashed and irie image.