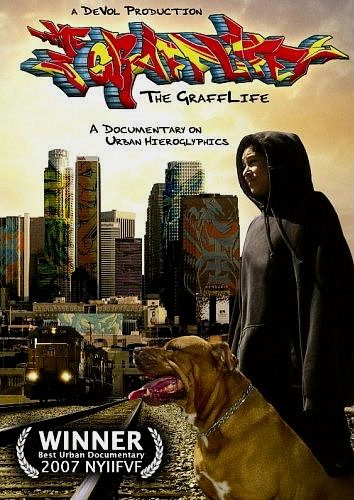

Graffiti is the one element of Hip-Hop that doesn’t result in personal notoriety. Unlike emcees, DJs and breakers, graffers, thanks to their actions being illegal, have to be known solely by their art. There can be no face recognition for these creative people and their fame has to solely lie in the work they create, work that may only be up for a short period of time. Randy DeVol’s documentary The Graff Life chronicled the struggles these artists go through for their art as he followed the lives of a crew of graffiti artists in southern California. This week RapReviews caught up with DeVol, whose mainstream production work includes numerous reality shows for the Discovery Channel, to find out what inspired him to create The Graff Life, how it changed his views on graffiti, and the role he feels the government played in fostering the growth of the illegal art form.

Adam Bernard: Start everyone off with some background. What was your original inspiration to make The Graff Life?

Randy DeVol: My original inspiration was an argument I got into with a graff writer. I’m an artist, a wall finisher, and I’ve done murals. I was working for a designer construction crew doing high end wall finishes, baby blue skies in baby rooms and hand painted foliage in kitchens, stuff like that, and I got to talking with a couple of the guys who were younger. We used to come in late to work and I asked one of them “why were you late” and he said “I was out painting.” I told him “I came in late because I learning how to edit (video) so one day I won’t have to be on a construction site.” He was like “yeah, we were catchin some spots.” I didn’t know what the hell they were talkin about. I was like “what do you mean?” That’s when the whole introduction came, “we’re graff writers and this is what we do.” I got into an argument saying “you’re gonna lose your fuckin job coming in late and at least I’ll have another job when I get fired because I was late because I was working on my new job. What the fuck are you doing painting?” Basically, he told me “don’t talk shit unless you know what it is we do.” I said “I don’t know what it is you do.” And he said “well, why don’t you come out and check out what we do and then you can talk some shit after if you want.” I said OK. He said “bring your camera if you want to shoot something,” so I did. I just shot one night mission, that piece never made the film, but I shot it and cut a little piece and I showed it to them and they loved it. They said they had never seen anything like that and they invited me to continue coming out with them. That’s how it started.

AB: So this was pretty much guerilla filmmaking?

RDV: Oh yeah, just straight documentary style, guerilla style.

AB: How did you make sure that it wasn’t just a rehash of Style Wars?

RDV: I knew it wasn’t gonna be a rehash because of the time that I was filming it. There seemed to be a small emission, or explosion, of graffiti right at the time, 2002 – 2003 and I knew a lot of the characters were just different. Style Wars were 80’s kids, which I was, and I knew these kids, I was dealing with 17 and 18 year olds who were growing up in the new millennium, and I just knew they were different guys. It was a different youth.

AB: I was in LA earlier this year and I took the train from LA to San Juan and I saw some really dope graff while on that ride. Was some of that done by the crew you chronicled?

RDV: Yeah, the crews that I chronicled are real active in LA and they do a lot of the, I would call it off-Broadway graffiti, that would be the non-Melrose graffiti, kinda the places you don’t see unless you’re on a train. Unless you’re on that train route you’ll never even get a glimpse of it.

AB: I thought it was great because I hopped on this train knowing I’d be on it for a while and for the first like 20 miles I saw nothing but graffiti.

RDV: Unbelievable, huh! Trains aren’t necessarily an LA thing. LA is about freeways and overpasses and under freeways for graffiti art.

AB: And the only reason I was on the train was because I didn’t want to rent a car.

RDV: You got lucky because you wouldn’t have seen any of that. Those places are great for graff writers, you can’t even see them from a freeway or a roadway. That’s where they like to do it, that area. It’s not really bothering anybody. It’s not like society is calling, or renters are calling saying I don’t like the way the graffiti looks here, can you clean it up?

AB: It was a good five to six years ago that you shot your footage; do you know where some of those artists you worked with are now?

RDV: Yes, I do. In the documentary I have an extra segment that’s called That Was Then and This is Now where I caught up with some of the guys. One particular guy is opposed to graffiti now. It had not paid positive dividends in his life and he’s not necessarily advocating graffiti like he did before. He was a really committed graffiti artist, but things went bad for him, he lost a friend in some gang shit. He had started a tattoo business and all of a sudden his business was subject to friggin small time terrorist gang banger shit. He was getting windows broken and bullshit like that. There was a shooting there and the tagger got into some rival shit, a gun came out and somebody got shot and died. I can completely understand where he’s coming from when he says “I am completely done with graffiti, it showed me something negative and I lost a friend.” Everybody feels different. That’s the interesting part to me, it’s such a vast demographic, they come from all walks of life and they have such different experiences and interpretations of graffiti, it’s just so different, everyone’s so different, but somehow their common ground is writing graffiti, rebelling through art somehow and making a social statement that society can see.

AB: How did making the film affect your view of graffiti?

RDV: It completely changed it. My original impression of graffiti was an ignorant one. I didn’t know much about it, but my ideas of it weren’t very positive. I was particularly surprised in the graffers’ dedication to their art, because graffiti is not something that they can keep, keep track of, or get paid for. It’s illegal. It jeopardizes their freedom, their jobs the next day coming to work, and their dedication to that and the integrity for their artistry is like no other kind of artist. A lot of artists talk about not wanting to compromise much of their art and staying true to their art, but I have not seen the kind of commitment and dedication and integrity for staying true to the art as I have in graffiti. They showed me an artistic integrity that I had not know yet and I’m an artist and I feel like I’m an artist with integrity and an artist that doesn’t compromise his art, but graffiti writers, I saw the way they’re dedicated to their art and that’s a whole other level of commitment.

AB: Throughout the film there was a loose correlation that the narrator wanted to try to get across about a lack of arts funding and graffiti. Do you really think that graff artists would want to be in a classroom?

RDV: I think at this point, because of the way graffiti evolved, most graffiti writers evolved from the streets and doing their art in the streets, so not necessarily. I think a lot of the inspiration comes from the lack of resources and the ability to be able to still create art and create a high level of art and express themselves artistically with limited resources, without a structure, without help or funding, so that’s a tough one. To be honest I think most of the graffiti artists I was dealing with probably find more comfort in the street and the freedom of not being restricted and having rules.

AB: To flip that, had some of those same artists had the benefit of growing up with a significant amount of arts funding do you think that they’d still all be graffers, or would some of them have responded to the art classes?

RDV: I think some of them would have definitely responded to the art classes. I think that some of them wouldn’t have even been graffiti artists to begin with. I’ve talked with guys who have said growing up and being from a poor family was part of the reason they became an artist. They wanted to express themselves artistically, rebelliously. Some said that maybe if they had come from a family with money they might have been in sports. Some of them can’t really say why they went into it. That came up when I asked why they did graffiti. A lot of them didn’t know why they did it. It was more a feeling they got, more like an unknown identification they made, but it felt like something familiar, it felt like something comfortable to them.

AB: So in the end the arts funding is affecting graffiti in that the less funding they give the more people they’re basically sending out to do graffiti.

RDV: In a sense, yes. There’s a good argument to be made for that, but I think it has more to do with the beginning and the birth of graffiti as opposed to the sustaining of it. There wasn’t a lot of graffiti art before the 1980’s. There was some, but that’s the way it started, because in this country we have the freedom to express artistically and when not given that opportunity through your normal avenues we’re still compelled to express artistically.