It’s a funny thing. With a few notable exceptions, I pretty much listen to hip-hop/rap. Still, even though I love hip-hop, or at least its potential, I can’t really say that I “like” hip-hop music. I follow it extremely closely. I try to listen to the new releases as soon as they come out. I write for RapReviews.com, for goodness sakes. But I’m really not sure I like hip-hop. If I liked hip-hop, why would so much of it piss me off?

More than any other genre of music, country included, I am most likely to dislike a given rap song. As a result, I tend to listen to a lot of hip-hop that can barely be qualified as hip-hop. My favorite album of the year thus far is P.O.S.’s “Never Better,” which is practically a punk album. My favorite of last year was Lil’ Wayne’s “The Carter III,” which is certainly rap, but certainly strange, and the year before it was El-P’s “I’ll Sleep When You’re Dead,” which borders on industrial….

After writing the last paragraph, I had myself a good think and came to the following conclusion: the reason I am so critical of hip-hop is because, more than most other genres, it tends towards conformity. Indeed, rap critics often criticize artists for not sounding enough like “rap;” you simply don’t find this tendency in rock or pop critics. To be sure, few artists of any genre are completely original, but, to a greater extent than many other forms of music, rap is characterized by group-thinking and deliberate mimicking. All types of rap, from the fringiest backpack rap to the catchiest club bangers, are filled with shout-outs to the past, declarations of geographic loyalty, and loop-recycling. Consequently, MCs and producers make constant overt efforts to pay homage to past greats, build a sound with those around them, and borrow already successful concepts. These tendencies result in hip-hop’s rich history and sense of identity but also in rappers, too often, finding virtue in sounding like someone else, and, well, that pisses me off.

Which is why I like Aesop Rock so much. This Big Apple native, Def Jux poster boy (now living in San Fran) is certainly a far from perfect MC. His breath control, while usually gifted, can be hit-or-miss, his verbiage obfuscating, and his tone oppressive. Still, from his surrealist rap-poetry, to his atypical flow, to his enchantingly ominous production, usually via Blockhead, he lives and dies by his originality, and that ethos alone commands my respect.

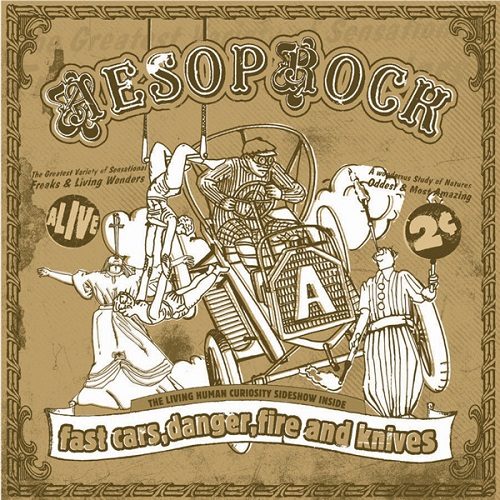

The “Fast Cars, Danger, Fire and Knives” EP, released in 2005, was Aesop’s seventh release in about as many years, if you count his pre-Def Jux releases, “Music for Earthworms,” “Appleseed,” and “Float.” The EP was his fourth Def Jux release. It came as a follow up to the largely self-produced, experimental “Bazooka Tooth,” after fans requested more Blockhead beats (although the EP is still less than half Blockhead-produced). Like Aesop’s entire output, “FCDFK” lives and dies by its uniqueness.

The first track, the EP’s namesake, features Aesop and Blockhead at their best. Blockhead provides a catchy horn riff over a subtle snapping percussion while Rock flows with his tongue in his cheek about his tastes for violence and decadence, bragging that he’ll “walk through every cipher with dynamite in a beer hat.” To be sure, “Fast Cars” is our Def Jukie at perhaps his most accessible, but, considering his previous work, the pop sensibility shown here demonstrates that he is stylistically agile, not selling-out.

Not to worry. There is plenty of weirdness packed into this little record. The Rob Sonic-produced “Winners Take All,” a poignantly existential war protest, finds Aes Rizzle as a soldier in an unknown location without specific orders. Every time he asks his commanding officer what to do, a voice radios in: “strap on a helmet and start shooting.” On “Holy Smokes,” over an appropriately clunky and tension-filled percussion, he offers an absolutely seething criticism of organized religion generally and Catholicism specifically. Despite its harsh critique, the song is not intolerant. Demonstrating the intellectual well-roundedness of the Aesop-Blockhead team, they insert uplifting Bible passages in place of a chorus; the track, thus, contrasts religion as practiced with more progressive biblical dictates.

“Food, Clothes, Medicine” is a generally successful experiment testing how many lines our MC can rhyme with the song title, as the repetition of “food, clothes, medicine” completes each stanza. Under the lyrics are cut-up ambience and hard-hitting, steady snare. Under that are porn sounds. I’m not sure why. The porn sounds work well enough to keep the listener’s attention for this song but also demonstrate a type of conformity that can pull Aesop down.

Def Jux is enamored with the extremely sordid. Sometimes it works, like on Cage’s 2005 LP “Hell’s Winter.” Sometimes it doesn’t, like on the Weatherman collaboration album, “The Conspiracy” (how did they expect a song called “Beverly Crabs” to be decent?). On “Riggity Rackety,” our NYC b-boy proves that even the biggest non-conformists conform, albeit in sometimes strange ways. On this track, easily the worst on the EP, Aes, Camu Tao, and El, for almost five minutes, spit contemptuous bravado – lying about threesomes they’ve had (“her pussy fit my dick exactly;” quite the coincidence considering that she definitely isn’t real) and making up lame nicknames for each other – but, in the end, just sound like they’re doing that thing Def Jukies do when they rep NYC in a feigned attempt to make themselves seem like pricks.

It is the avoidance of this kind of unproductive aping of crew and region that generally sets Aesop Rock apart. These strengths are definitely present throughout most of “Fast Cars,” but, at points, Aes and Blockhead seem like they are overcompensating to make up for the experimentalism of Rock’s previous album. “Number Nine,” for example, has the potential for brilliance, as A.R. flows nicely over Blockhead’s slithering electro, but it feels like the two are holding back. The staccato vocal sampling in the chorus, for example, is kind of interesting, but it’s a run-of-the-mill sort of interesting, not worthy of actual intrigue. The same can be said for the self-produced “Zodiacupuncture,” on which Aesop blazes through the verses over distorted neo-soul. On the whole, though, the track neither commits to pop nor weirdness and instead lingers in 6-out-of-10 indie-rap Purgatory.

Still, to criticize Aesop Rock too strongly for not being constantly innovative would be to hold the bar too high. In fact, trying to innovate all the time results in its own type of conformity, as a crew’s attempts to mold a new style often wind up in a lot of the participating artists ripping off each other. (I’m looking at you, Anticon). “Fast Cars, Danger, Fire and Knives” is a general success, not because Aesop is trying to be different and not because he is trying to be the same, but just because he is doing his thing.