“My voice travel like that smell when they burnin the ‘dro

On the tour bus they searchin’ the coach

in the airport they searchin’ my coat

they say they searchin’ for dope

‘Legal Drug Money’ stickers on the back of my bag

the only artifact from my past that I still have”

(Canibus, “It’s No Other Than” ’05)

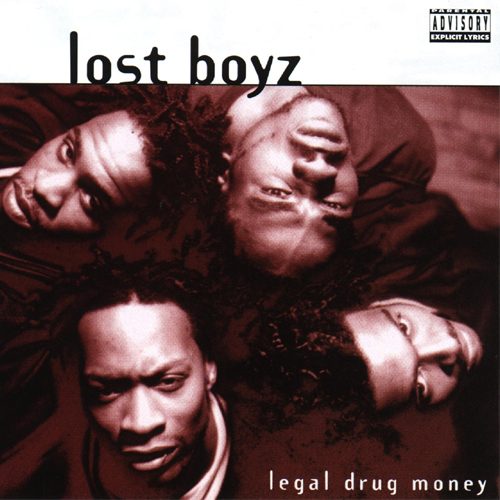

Heads old enough to remember a time when LB didn’t stand for Little Brother may recall that before the Wyclef Jean connection that resulted in the ill-received “Can-I-Bus” debut, it were the Lost Boyz who gave lyrical carnivore Canibus his first exposure (thanks to their mutual manager Charles Suitt). Along with other early appearances, his two spots on their sophomore effort “Love, Peace and Nappiness,” especially “Beasts From the East,” raised expectations sky-high. Turns out, Bis could already be heard (credited as Canibus The Bugdealer, curiously) a year before, on a visionary L.T. Hutton remix of “Music Makes Me High” featuring Tha Dogg Pound. Since then, Canibus has pursued a rather peculiar career path, rarely ever looking back, but it’s easy to see why he would hang on to an old sticker that reminds him of a time when the future looked nothing but bright.

Amidst bi-coastal beef and in the heyday of Death Row and Bad Boy, the Lost Boyz were able to carve out a niche for themselves with their infectious party vibes. “Legal Drug Money” contains five singles (released between ’95 and ’97) that cracked Billboard’s Hot 100 and rose as high as between positions 3 and 11 in the Hot Rap Singles charts. The two ’95 singles were both produced by Easy Mo Bee at the height of his career, when he was working on 2Pac’s “Me Against the World” after being heavily involved in The Notorious BIG’s “Ready to Die.” “Lifestyles of the Rich and Shameless” is trademark Easy Mo symphonic boom bap, a melodically pleasing backdrop for the serious hood tales. Rapper Mr. Cheeks gives a detailed characterization of two youths engaged in illegal activities, before turning the focus on himself and how he got out of the game.

The next single charted slightly lower but marks the apex of the Lost Boyz legacy. Turned down by Bad Boy artist Craig Mack, the beat to “Jeeps, Lex Coups, Bimaz & Benz” is a great combo of danceable-but-not-dancey drum programming and a sparse organ groove sprinkled with these weird chimes that make the track instantly recognizable. Cheeks makes this unique track completely his own, particularly with the enthusiastically delivered hook:

“A shout out to the Jeeps

the Lex Coups, the Bimaz and the Benz

to all of my ladies and my mens

and all of my peoples in the pens

keep your head up

And to the hoods, East Coast, West Coast and worldwide

ain’t nothin’ wrong with puffin’ on lye

and if you’re with me, let me hear you say, ‘Right, right…'”

The album version, somewhat to the reviewer’s dismay at the time, adds minor keyboard elements that may diminish the bump factor a bit, but to new listeners it should nevertheless prove addictive. Music aside, Cheeks gives a strong performance, calling out competition not just lyrically but also with the mandatory vocal presence:

“Who’s the best, who’s the worst in this here rap game?

For those that claim, to be the best, I tear ’em out the frame

I’m representin’ puttin’ Queens on the map

(What you wear?)

Double springs with some baggy jeans when I rap

Come up with a style that they call versatile

Don’t treat me like no lame, I’ve been in this game for a while

I’ve seen a lotta come, I’ve seen a lotta go

I’ve seen a lotta break, I’ve seen alotta blow, aiyo

It’s a trip to see a nigga slip

Get a grip nigga, nigga, get a grip, get a…

You don’t even know the half of my crew

to be talkin’ like you’re talkin’ and to you act like you do

Yo set it, you fuckin’ crossed my line and hit the border

LB Fam start attackin’, someone’s actin’ out of order

Put on your leather gloves and hats and get your pitchin’ bats

And get the gats just in case we take it to the stats”

Cheeks’ sometimes hesitating flow and slightly inebriated tone belie his stature as an MC, yet it’s also those qualities that make him stand out from the crowd. He doesn’t have the most complex vernacular, but like so many simply efficient rappers, he had what it takes: “From Jamaica comes a nigga named Cheeks with techniques for the streets over ruffneck beats.” What more could you ask for?

Various rappers may fall into that category, but with Mr. Cheeks it was evident that he’s a man of the people. While he’s practically the group’s only rapper, he never hesitates to shout out his crew, which, as he alludes, extends beyond fellow core members Freaky Tah, Spigg Nice and Pretty Lou. The crew back-up is a familiar element of rap, but in the case of the Lost Boyz you really get the impression that there are more folks in this “tribe than there’s bees in a beehive.” One key element in forming the impression that you’re dealing with a whole tribe is the late Freaky Tah, a relentless hypeman who is so present he becomes part of the musical tapestry. Building on the rugged, free-flowing antics of Nine and Ill Al Skratch, he brings a distinct counterpoint to Cheeks’ youthful and well-timed flow.

After originally signing with Uptown Records, the Lost Boyz came into the fold of Universal. But their next single, “Renee,” was released through Island, since it was on the “Don’t Be a Menace to South Central While Drinking Your Juice in the Hood” soundtrack. It became the group’s best selling single, going gold in ’96, days after the release of the album, which too went gold within two months. The Mr. Sex-produced “Renee” is also the most atypical Lost Boyz single, a musically stripped down love story that ends tragically, prompting The Source (6/96) to note: ‘It rivals Method Man’s “All I Need” in expressing the dynamics of male/female relations for the average b-boy. But this on-point sentimentality is somewhat underminded when, as with The Notorious BIG’s “Me & My Bitch,” the adored female in question meets an untimely death. Cheeks makes you feel the loss, but you privately question why ghetto love is so often represented as doomed.’ On a slightly related note, another track that had appeared prior to the album was the Pete Rock-produced opener “The Yearn,” the safe sex theme recorded for “America Is Dying Slowly.”

The second ’95 single, “Music Makes Me High,” works with a sampling staple, “Bounce, Rock, Skate, Roll,” cunningly arranged by Mr. Sex, while Cheeks and crew bring their characteristic mixture of shout-outs, calls to keep it real, lyrical attempts (“What I write down the line gives sight to the blind”), social awareness (“All my niggas doin’ bids / all of my shorties on they own raisin’ kids”), straight up representing (“‘Bout to put it on ’em for the year nine-pound / I represent my town, show ’em how I get down”) and the obligatory extended hook. 1997 finally saw the release of the last single, “Get Up,” a legit club tune by Mr. Sex, who’s also present with a “Lifestyles of the Rich and Shameless” remix.

The rest of the production is largely signed by Big Dex, a neighborhood beatmaker who might have been the first to work with the Lost Boyz (some of the tracks bearing the ’94 stamp). He raps alongside Cheeks and Tah in the round-the-way cipher “All Right” and produces the relaxed head-nodder “Legal Drug Money,” which explains the album title by relaying that music is a drug to them. More tracks dwell on the subject, some (“Keep it Real”) being more consistent efforts than others (“Da Game”). Cheeks and company retain a hood perspective but do at times point to the bigger picture. On “Straight From Da Ghetto” he explains the moral dilemmas that shaped his character, to the point where he had to listen to the devil on his shoulder:

“I been away, so mad peoples thought I fell

but I just came back from a visit in hell

I seen the demon and we chatted

about this and that, all the foul things that never mattered

He said, ‘It’s time to get your props

but still watch your back for jealous fellas and them crooked type cops’

So yo, I did what he ordered

Police never reported the day they found my little man Shawn slaughtered

Some kid slit his throat for a leather coat

but we caught the suspect, 911 is a joke”

Speaking of Public Enemy, “Channel Zero” is the album’s politically most outspoken tune (declaring, “The Black Planet is near”), Cheeks pouring his heart out over Big Dex’ mournful strings buried under layers of bass. In a potshot, he also attacks white rap sensation Marky Mark (who arguably was long done by ’95): “You gets awards for your bullshit skills, gee / A white boy actin’ black, that shit kills me.”

Their complaints notwitstanding, the Lost Boyz seemingly did find a way to escape fate. They turned frustration into celebration and became an integral part of mid-’90s New York rap. Still tragedy struck when Freaky Tah was murdered in 1999. To hear him rap from an assailant’s perspective on his solo track “1, 2, 3” can be irritating, but the song should be played until the end before passing judgement. He’s even clearer on his ultimately peaceful philosophy in the title track, where he fatefully raps:

“I heard this nigga went crazy on the train

At first I thought he was nuts but at the same time I feel the pain

Cause another nigga’s dead on the streets over dumb shit

like, ‘Nigga-where-you-from’ shit

It bothers me on the norm, I stand tall

with my back against the wall, and my hand on my four-four

(Aiyo, what about the world, Tah?) The world seems to bug me

don’t know who wants to kill me, don’t know who wants to love me”

“Legal Drug Money” has an undeniable place in 1990s East Coast hip-hop history. It doesn’t deny its hustling roots, but it doesn’t glorify the hustle. Rather it points out the hardships, both for real hustlers and for these self-described “Legal Drug thugs” trying to make it in the recording industry. There’s a refreshing regular appeal to the Lost Boyz, who deliver an album ordinary people can relate to while still representing for their core constituency. Cheeks specifically can be considered a trendsetter with his melodic flow, foreshadowing a time when rappers would break into the mainstream with their sing-song style (Nelly or even fellow Jamaica, Queens native 50 Cent). Neither to be neglected are the hooks, which he delivers in a very memorable manner. He’s also a solid storyteller and knows how to put situations and emotions into words, from “Right now I push a knapsack with some Timbz / but I’m soon to push a black Ac with deep-dish rims,” to “Believe I been through all the struggles and the pain / I’m rippin’ out my hairs and I can’t get to my brain.”

At times “Legal Drug Money” feels like a definitive statement, one of those albums that encapsulate an era. That, however, doesn’t yet make it a classic. Still, a lot about the Lost Boyz is vintage hip-hop, from the lead rapper/crew backing line-up to their diverse hit singles. Not to sound patronizing, but this is probably an album that a self-respecting rap fan should know.