“My real world realer than rap”

(Method Man, “Mef vs. Chef 2” – 2010)

So-called reality television is just about the format with the highest degree of falsehood you are going to find on the idiot box these days. Which is not so much because fictional programming would be particularly realistic and chock-full with real-life relevance, but because the term reality TV suggests actual people spontaneously acting and interacting in authentic situations. Yet if you ever gave the work behind broadcast only the slightest thought, you can see how much logistics, planning, scripting, editing, etc. goes into anything that is shown on the small screen that makes somewhat sense and looks halfway decent. And that’s not even considering the influence of the omnipresent camera and microphone. Some reality shows handle that paradox well by acknowledging it, others still fake hard.

While it had existed before, reality TV became the media buzz word when MTV began airing a series entitled The Real World in 1992. Essentially a social experiment, it gathered some seven strangers under the same roof to see how the different characters would clash. The first season of The Real World was staged in New York City, and it featured a cast whose members visibly were from different walks of life. The show kept its promise to present life in a goldfish bowl and, to this day, counts on the spontaneity of the cast members as it seems to be less orchestrated than your average reality show. Subsequent installments of The Real World (currently in its 23rd season) proved sporadically interesting, but after a period of loaded and conflict-laden set-ups the producers began to enforce the element of romance to the point where more recent seasons and similar MTV formats focused almost exclusively on the housemates’ mating rituals.

The original New York cast included a young woman named Heather, who was introduced as an aspiring rapper. Heather was outspoken and opinionated but still had an air of incertainty and inexperience about her – which was the intent of the makers all along, to show how young people who may seem like fully formed personalities at home, adapt to new surroundings and situations. Heather’s direct and open manner made her one of realer characters on The Real World. Though she managed to get herself detained by police towards the end of the season, the friendly disposition below her tough exterior played no small role in the initial strangers parting as friends.

She could also be seen in a rapper’s professional habitat – the studio, where she, we were told, was working on her debut album. Prior to the show, the rap artist Heather B had only a couple of cameos to her name, one “7 Dee Jays,” a CD bonus track on Boogie Down Productions’ “Edutainment” album, the other “Don’t Hold Us Back” on KRS-One’s H.E.A.L. project. The studio sequences showed Heather being coached by BDP’s Kenny Parker, but apart from that on The Real World the rapper was simply Heather. The Jersey girl struck up an unexpected friendship with Julie, a country gal from Alabama, who went from asking Heather, “Do you sell drugs? Why do you have a beeper?” in the first episode to making an appearance in the video for her debut single “I Get Wreck.”

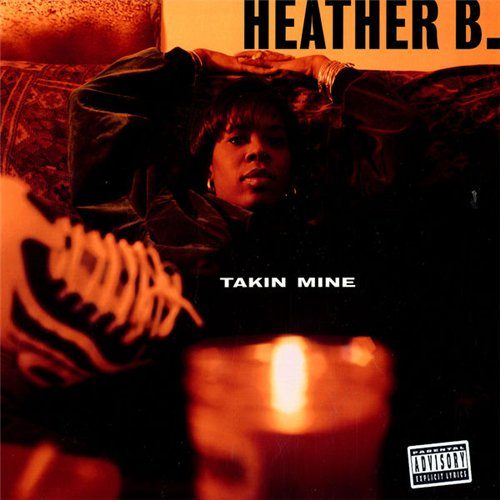

A slice of vintage uptempo ’93 boom bap, “I Get Wreck” wasn’t followed up until 1995, when mixtape sure shots like “No Doubt (Get Hardcore)” and “All Glocks Down” announced a full-length. While there had been a video for “All Glocks Down,” “If Headz Only Knew” can be considered the lead single for the album, 1996’s “Takin Mine.” In all likeliness none of the LP’s songs were recorded in the studio sessions mentioned above. It’s relatively easy to tell by listening to “I Get Wreck,” where she declares: “I used to get weeded but now I hate the smell / so I stop just to keep my braincells / Don’t like the feelin’ of bein’ high / like to stay down-low and write dope rhymes.” For “Takin Mine” she pulled a Dr. Dre, openly writing and rapping under the influence.

While not taking it to “Gangsta Bitch” extremes, Heather B does present herself as a tomboy (‘rowdy’ and ‘rugged’ are her favorite adjectives) who values the opinion of male friends higher than that of female peers. She rolls with a collective named 54th Regiment, two members of which are featured on “Real Niggaz Up.” Fooling anybody who thought “All Glocks Down” would advocate gun control, “the bulletproof lyricist” simply warns gun-crazy rappers that bullets are no match for deadly rhymes.

Kicking the level of aggressiveness up a notch, “Da Heartbreaka” lashes out in all directions. The first song, and she already comes out guns blazing:

“I prosecute bitin’ bitches to the fullest of the law

There’ll be no boostin’, there’ll be no lootin’

Glocks down? Fuck that, I’ll start shootin’

No trespassin’, no intrudin’

Wanna-be hoods want my spot ruined

You better watch yo back or it’s BLAOW

We ain’t peeps cause you smoke lah now

You ain’t come around back when I wasn’t smokin’

now all the time you wanna be tokin'”

Any hopes that Heather B would be a little bit more like Heather from The Real World are crushed when she rhymes: “I only want niggas and shorties to know me / They feel what I feel and they talk what I talk / I gotta please heads in New Jerz and New York.” That frame of mind is the very opposite of what The Real World tried to foster as she deliberately holes herself up into a ‘ghetto of the mind’ (as Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth put it in ’92). Lines like “They tellin’ me I can’t talk to the streets no more, are they stupid?” suggest she’s reacting to pressure to use the show as a springboard to crossover. Ultimately, it seems she isn’t totally comfortable with her stance as she ends the song with “It’s a shame, son, I got to be on it like this / but it’s time I let ’em know, I’ll have none of this shit.”

While “Da Heartbreaka” smacks of over-reaction, “If Headz Only Knew” is a heartfelt dedication to hip-hop. Famously interpolated by Big Shug at the beginning of Gang Starr’s “The Militia,” the song’s chorus is an inspiration to any struggling MC: “If heads only knew how I felt about the rap game / they’d know – I ain’t goin’ out.” She backs the claim up with a solid performance to the considerately crisp, flavorful beat:

“‘I’m Every Woman’ like Whitney and Chaka

I sparks the green lah, the choc’ thai, that good ganja

I stay mad bent, twisted up like a pretzel

Rainin’ on hoes in weak shows like Tempestt Bledsoe

My head so heavy, heavy-headed, heavy-handed

It be these wild niggas that I roll and stand with

I be rhymin’ till dusk ’bout trials and triumphs

My grill be like, ‘What!’ Niggas know I don’t give a fuck

I stay in touch with the streets, the corners

employed by the people; start slackin’ – a goner

You wanna know why I keep it real? Cause it’s easy

Fuck the fancy shit, it’s the simple things that please me

I sports fat gear along with no-name shit

As long as I got me some cash, I don’t care who name on my hip

I’m doin’ shit for noventa y seis

that’s nine-six in Spanish

Why don’t yo wack ass vanish?”

If there’s one imminent quality about “Takin Mine,” it’s that in many of the tracks the beat and the rhymes operate at eye level. Heather’s attitude is equaled by Kenny Parker’s heavyweight compositions. With beats just as authorative as their rapper, “Da Heartbreaka,” “All Glocks Down,” and “If Headz Only Knew” are mid-’90s hardcore hip-hop masterpieces. Ditto for “No Doubt,” sampling a Biggie quotable that just begged to turn up in a song sooner or later. The confidently swaggering beat matches the message to a tee as Heater gets wreck one last time at the dawn of the jiggy era:

“Y’all remember ‘Um Tang, Um Tang’?

Well now nuccas holler ‘Wu-Tang, Wu-Tang!’

This be a Jersey thang-thang, nothin’ but street slang

Nothin’ but blunts hang from the lips of this lyricist

You try and diss, it’s a mistake but I’ll excuse you

Lose you, defuse you if you claim to be the bomb

Y’all corny mothereffers and y’all slick-talkin’ heffers

Y’all uppers and your lower lips need sewin’ together

Y’all talk more shit than Al Sharpton when the mic on

In person you’se a bitch with tight white panties on

Bitch-ass, trick-ass, you can’t rhyme

Prepared me for take-off, I’m leavin’ niggas flatlined

( *flatline* )

I came with that eenie-meenie-minie-moe

and caught a sleepin’ rapper by the toe

I’m undisguised, you recognize me

in the black jacket and boots made by Polo

A sister that be rockin’ solo

[…]

In 2000 I ain’t checkin’ for no heroes

I just wanna sit back and count mad dinero

And have the CREAM comin’ from my rear, yo

I speak crystal-clear, so I know that you heard me

Heather B be the one hollerin’ ‘Jersey!’

Chilltown up in this piece

And the Coast be the motherfuckin’ East

No doubt”

While she professes that she wants to be “more illmatic than Nas,” Heather B is neither the most gifted writer nor rapper. But while she struggles to voice much else than frustration and determination, she has the ability to get to the point and assume her supposed superiority with concise phrasings. She comes up with statements that somehow stick, whether it’s a simple “I’m classic like a Coca-Cola,” or a more tongue-twisting “These drums will be hummed throughout all the ghetto slum.”

Conceptually, she sometimes aims higher. There’s a b-ball-themed verse in “If Headz Only Knew,” one about crooked cops in “Real Niggaz Up.” “My Kinda Nigga” must almost be considered an MOP song, the sequel appearing on “First Family 4 Life.” The closing “What Goes On,” g-funked out with a “Summer Madness” sample, is a ghetto romance with both comical and serious elements. The slightly R&B-tinged title track does not just contain a verse reminiscent of Nas’ “If I Ruled the World,” it’s where both Heathers, the unknown rap fanatic and the Real World housemate under constant camera surveillance, join hand in hand:

“From now on I’m makin’ moves, fuck plans

That’s the shit I’m on as my front door slams

And fuck these neighbors, they’ll never understand

but one day I’m gonna make ’em all big fans

Turned on my light and took my coat off halfway

then sat down and sparked up the roach in the ashtray

Plugged up my beats and took off my Nikes

No kids in my crib, hip-hop gives me life

That black and white notebook, damn, I can’t find it

Been thinkin’ all day, now lyrically I’m inspired

I pray every day a stray bullet won’t take me

I got to live to see where I finally make me

I got the hots for fat knots and drop-tops

I’m gonna be more than a girl with a hair shop

The writer’s block, ock, I’ll knock and chop

I’m goin’ for my shot at this game called hip-hop

I’m gon’ stop all the Heather-cannots

with a box of can-dos and all types of what-nots”

The cast member to parlay his Real World fame most effectively into a career in, well, the real world, was model Eric Nies, who, with MTV’s help, enjoyed a prolonged stay in showbiz, mainly as a television host. Kevin Powell came to prominence as a writer, journalist and political activist. In hindsight it is interesting to note that Powell wrote for VIBE magazine during exactly the period between The Real World and “Takin Mine.” Though both black, from New Jersey and members of the hip-hop generation, him and Heather never truly bonded (on-air, at least), and one can only guess what his take on this album’s testosterone-fueled tone would have been, particularly as (as his Wikipedia entry describes him), ‘an outspoken critic of violence against women and girls, of violence in general,’ who ‘has been at the forefront of the movement to redefine American manhood away from sexism and violence.’

Sexism? Well, on Heather’s part there is the reflex adaptation of essentially homophobic terms like ‘bitch-ass.’ But more importantly it’s the degree of her denial of any feminine take on rap music that is startling. This female rapper goes as far as justifying the opinion that “females can’t rhyme,” adding, “That’s why real niggas got to keep this shit true.” It seems she can only express herself with male language, the line “If I ever grow a dick you’ll be on it” representing the tip of that particular iceberg. In her defense, especially “All Glocks Down” radiates a kind of maternal authority no male peer could muster, to the point where the song ultimately still can be taken as an anti-gun anthem.

So “Takin Mine” isn’t a balanced record. That’s one reason to champion it, especially if ‘balance’ means catering to as many demands as possible. Shoving aside all expectations except those from the hardcore constituency, Heather B rips through her material like an East Coast version of Lady of Rage. Defiant from the opening line “Raise yo L’s and yo middle left finger,” she combines freestyle aesthetic and personal drive in a potent musical one-two punch. Just to keep things in balance, however, after “Takin Mine” you might want to listen to Missy ‘Misdemeanor’ Elliott’s own acknowledgement of MTV’s real-life soap opera, “Da Real World,” an arguably more complex and diverse piece of music.

For close to twenty years now The Real World promises to satisfy your curiosity as to “what happens when people stop being polite and start getting real.” Back in 1992 when rap ruled my world, my reply to that would have been that if you want to witness people getting real, all you have to do is tune in to hip-hop. Today I see rap mostly as a form of entertainment, and while I view some of the peculiarities of “Takin Mine” as concessions to the form of entertainment that is rap, Heather B does, in her very own way, keep it real on her debut, particularly in view of her Music Television fame, which was derived not from any music of hers but the fact that she happened to be chosen to be on TV. With so many people who are famous for being famous nowadays, Heather B, despite occasional later on-screen appearances (‘Ricki Lake’), stands as someone who preferred creative expression and hard work over a meaningless celebrity status. Even her MTV bio back in in the day stated: ‘Heather B may truly be as real as it gets.’