While my knowledge of Jamaican popular music is massively underdeveloped, I know this much – the importance of its musical masterminds easily rivals, if not surpasses, that of rap music/hip-hop producers. They can have unassuming job titles such as sound engineer or rhythm section, but names like King Tubby, Sir Coxsone Dodd, Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, Sly & Robbie, Bobby ‘Digital’ Dixon, Dave Kelly and Steely & Cleevie were and are key figures in the undiminished popularity of reggae et al.

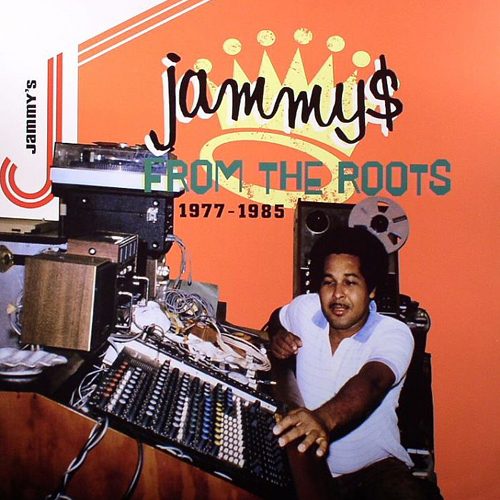

Lloyd ‘King Jammy’ James got into the game as a tech guy, building sound system equipment and soon also running his own in Kingston’s Waterhouse district. He joined dub pioneer King Tubby as a recording engineer, a period when he was crowned Prince Jammy, before producing records himself by the late ’70s, including Black Uhuru’s first album. The typical blue-and-white labels on countless 7″s released on Jammy’s Records quickly became a seal of quality. Jammy permanently put his name in the history books in 1985 when he put out Wayne Smith’s “Under Me Sleng Teng,” the song that ushered in the digital age in reggae music. From the mid-’80s on he specialized in what he (pardon the pun) dubbed “Computerised Dub” (see the ’86 album of the same name) and dancehall riddims, becoming, according to The Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music, ‘the undisputed king of computerized, digital reggae music for the ’80s.’

The Greensleeves compilation “From the Roots” documents Jammy’s production career prior to “Sleng Teng,” with an emphasis on roots reggae, the prevalent form of reggae in the ’70s. In hip-hop, the equivalent of roots reggae would be conscious rap, with the difference that too much spiritual content would quickly cast it into the gospel rap category. With the Rastafari ideology emerging in Jamaica and reggae music being an internationally recognized vehicle to praise Jah, spiritual songs are a sure thing on any compilation focusing on that period.

Johnny Osbourne’s consoling “Jah Ovah” points back in time with a ’60s rhythm and blues influence with a prominent organ rising above the steadily pulsating track accentuated by clear, sparse drums. Hugh Mundell’s “Jah Fire Will Be Burning” has undeniable funk genes in its lineage, while The Travellers’ “Jah Gave Us This World” swings at a peaceful vibe as the lyrics ponder how we exactly earn the privilege to live in this world we were given. The longest track at over 9 minutes and concluding the first CD, Lacksley Castell’s “What a Great Day” revels in the vision of a day when god’s children will be free, the horn-driven track musically expanding on the idea in its dubby second half. Further evidence of the musicians’ humble, god-fearing attitude can be heard in tracks like “Jah Do Love Us” by The Jays and “Children of Israel” by Frankie Paul.

But the message can also be delivered without a spiritual superstructure. Johnny Osbourne voices righteous anger about senseless violence in 1980’s superb “Fally Ranking.” Never simply dwelling on the negative, these artists juxtaposition harmony against conflict, modesty against vanity, responsibility against recklessness. Black Uhuru urge us to seize the moment on “Tonight Is the Night to Unite” and wish for “peace and love in the ghetto” on “Willow Tree.” The vocal harmonizing of Black Crucial sets the tone for their “Conscience Speaks,” an invocation to let your conscience guide your actions. Junior Delgado calls an end to centuries of conflict on “Liberation.” And on “Youth Man” Noel Phillips invites young men to seek unity because “the youth of today are the men of tomorrow.”

One property of reggae songwriting that can also be found in American rap is when the lyrics directly address and accuse an authority. Earl Zero does it downtrodden on “Please Officer” (“Victimisation, that’s what I-n-I get in Babylon / brutalisation, that’s what I-n-I get from Babylon”), whereas Johnny Osbourne points his finger bluntly in one general direction on “Mr. Marshall”:

“Oh Mr. Marshall (Mr. Marshall), we finding you partial

Oh Mr. General (Mr. General), you cause too much funeral

Oh Mr. Sheriff (Mr. Sheriff), you cause Jah-Jah children to perish

Oh Mr. Lieutenant (Mr. Lieutenant), you’re asking for repentance”

Half Pint asks his landlord to ease up on him considering that “the roof is leaking, the pipe without water” and “the kitchen filled with rats and roaches.” Whether it’s Half Pint’s “Mr. Landlord” or “One Big Ghetto,” experienced rap listeners will have no trouble picking up arguments and sentiments they heard from the likes of Scarface, KRS-One, or Chamillionaire. Songs like Prince Alla’s “Last Train to Africa” and Dennis Brown’s “Africa We Want to Go” furthermore recall the brief but intense rap era that championed Afrocentricity, although I can’t think of any US rapper that went as far as advocating a return to the motherland.

Musically, insiders are likely to make some discoveries on “From the Roots.” As an outsider, I found the voiced versions interesting, U Black’s revisiting of “Jah Gave Us This World” on “Natty Dread at the Controls” and particularly the marvellous “Pablo in Moonlight City,” an instrumental take on “Please Officer,” where Augustus Pablo’s wistful melodica meets Jammy’s dubbing wizardry.

Apparently, the second disc showcases the growing presence of digital instrumentation, although this reviewer could only identify a distinct digital vibe in Junior Reid’s “Boom Shack-A-Lack” from ’85. Underlining Jammy’s dedication to reggae before the emergence of dancehall, the liner notes quote him: “I prefer singers and instruments… horns and harmonies. I love sweet music!” With Junior Delgado’s “Love Tickles Like Magic,” Natural Vibes’ “Life Hard a Yard,” Barry Brown’s “It a Go Dread,” Frankie Jones’ “Collie George,” and Dennis Brown’s “They Fight I,” there’s no shortage of the above.

From the leadership of the bass to the use of local patois and slang, these two CD’s highlight some of the characteristics shared by the not so distant relatives named rap and reggae. Prince/King Jammy’s work might furthermore prove interesting for hip-hop heads as he’s noted for his crisp, crystalline sound and the orchestration is often so subtle in incorporating elements you’d think sampling was involved. But obviously, this is music that was created before the advent of electronic sampling even in hip-hop, the riddims laid down by a long list of musicians. And then there is the staggering diversity of the songs recorded at Jammy’s, which is something very few rap super producers have actually mastered.

For Jammy’s impact on the ’80s and ’90s, please refer to the “Selector’s Choice” compilation series. Hearing his earlier productions on “From the Roots” makes his oeuvre even more impressive and from a rap fan’s perspective it kind of makes you wish we’d take a page from Jamaica when it comes to estimating the pioneers.