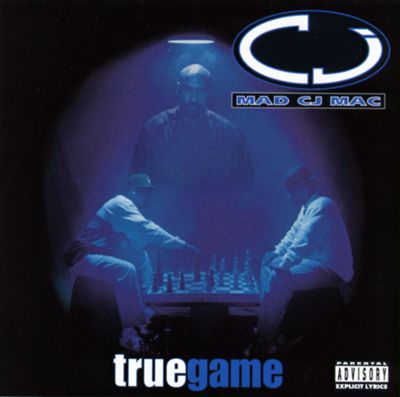

Like countless of his West Coast brethren in the 1990s, many listeners remember CJ Mac for a few minor contributions to the hip hop canon: a few strong but short-lived singles, a handful of high profile guest appearances, and the periodic acting cameo. Further examination of his output, however, reveals a versatile artist and unusually talented performer, provoking on the microphone and equally capable behind the production boards. Already in his thirties when he debuted with “True Game” in 1995, the South Central native dropped a quiet gem on the gangsta rap-listening populace that still shines even among the slew of potent g-funk-inspired records to emerge from California that year.

Originally scheduled to be released by Ruthless Records, CJ inked with J. Prince at Rap-A-Lot, who after the success of Oakland rapper Seagram was looking to expand his Houston-based label into a national empire. With production by CJ and mixing by RAL mainstays Mike Dean and James Hoover, the album spawned two videos and performed considerably well on the charts despite a lack of national airplay. CJ’s rhymes and lyrics hit equally hard throughout the 51-minute record. His production technique strikes a clever balance between the lean, dark, and furious sound of his Rap-A-Lot contemporaries—he would be featured prominently as a producer and guest on Bushwick Bill’s acclaimed “Phantom of the Rapra” and Poppa LQ’s “Your Entertainment, My Reality” later in ’95—and the woozy, synth-heavy g-funk of his native West Coast. He has a distinct sound, rarely varying his instrumentation, making for a consistent and focused record musically; grim yet funky, with rolling, pounding basslines, whiny synthesizers, and thundering percussion that scream South Central. On the mic, CJ sports a forceful delivery and commanding presence backed by substantial content. Vocally deep and aggressive, he raps about his years spent selling drugs and leading a life of crime and mourns his peers lost to the lifestyle, but proves most compelling when challenging government and the penal system. Although some of the later tracks stray into the proverbial, “True Game” boasts a tracklist of generally inspired material.

The startling intro thrusts the listener right into CJ’s bleak world, portraying an apocalyptic prison setting and biased court that dooms men unnecessarily to lives behind bars. The dreary “Let My Niggas Out Tha Pen” finds Mac at his most inspired, highlighting the hypocrisy behind sentencing for the poor and unemployed, the injustice of three strike laws, racist officials, and theorizing that drugs are only criminalized because they can’t be taxed:

“Ain’t nothin’ violent ’bout the shit he stood fo’

It’s always wrong when niggas stop bein’ po’

What the fuck we s’posed to do? How we s’posed to eat?

How the fuck am I supposed to keep shoes on my feet?

We didn’t bring the crack in, so why we gettin’ charged?

I don’t own no fuckin’ plane or no fuckin’ barge

We on the lowest level, still we get the most time

While the rich stay rich and drink the best wine

Now cigarettes done killed more men than cocaine

Alcohol done killed more men than cocaine

They decide to tax the shit, so now the shit’s legal

Drunk drivers on the prowl, they killed a gang of people

If they could control the crack, consider crack controlled

Slap a tax on crack and now it’s at your local liquor store

They don’t give a fuck about a nigga dyin’

They just can’t tax the shit, that’s why the fuck they cryin'”

Regardless of your take on CJ’s provocative subject matter, “Let My Niggas Out Tha Pen” is an intensely stimulating track with a rumbling, funky beat, culminating in an incensed monologue. The industrial funk of the title track soon gives way to the swirling synths of the single “Come and Take a Ride,” a brilliantly laidback duet with fellow South Central rapper Poppa LQ. The lush keyboards and soulful guitars make for a contagious head-nodder, but even over such a gorgeous, relaxed backdrop LQ can’t help but look back wistfully:

“Now you can go to any ghetto and find some thugs

But in California, folks, we got these Crips and Bloods

And it makes me wanna reminisce to way back when

Before eleven-year-olds had to hold a mack ten

I’m talkin’ about the days we used to blaze

And bump to Frankie Beverly and Maze, and Marvin Gaye

Damn, the streets ain’t what it used to be

We used to squabble for our set but now they shoot ya, G”

CJ remains downtrodden on the mournful “Realism” and the stunning “Losin’ My Mind,” a phenomenally-produced track with driving synths and choppy sax that finds CJ struggling to grasp with reality with conviction that makes it impossible not to feel his desperation:

“Man, is it me or everybody else done tripped?

How many times can I make the same slip?

Trustin’ folks I thought I could trust like it’s poppin’

But every time I trust one, they flippin’ and they floppin’

And now they even stealin’ from me

And it’s the same folks I thought would do some killin’ for me

Man, it’s gettin’ kinda hard to defend

If they close, then they’re gettin’ closer by the minute

Ain’t nothin’ stronger than your family

That’s why I’ll tear ya ass up when they see me G

Damn, it’s hard to stay strong ain’t it black?

Sailin’ through your hood with a knife in ya back

Ain’t seen my babies in months

My babies’ mommas can’t separate their needs from their wants

But still I gots to stay down, strictly doin’ mental time

That’s why I wrote this rhyme, ’cause I’m feelin’ like I’m losin’ my mind”

The second single “Powda Puff” is carried by the strong production and Mac’s deep, soulful delivery, and “Can’t Cee Thee Ahh!” continues in the same woozy vein. Although the hood profile “Tryina Survive” and formulaic “Trust No” are forgettable in light of the first half, “Dead Man Walkin'” features one of his finest productions, a slow and funky standout, and he rhymes with a vengeance on “I Can’t Stand a Rat.”

After “True Game,” CJ managed to bounce around multiple major label rap subsidiaries during the twilight of the West Coast’s heyday, appearing on numerous Priority projects and compilations such as Ant Banks’ “Big Thangs,” Sik-Wid-It’s “Southwest Riders,” C-Bo’s “West Coast Mafia,” and the soundtracks for “Friday,” “Gang Related,” and “Thicker Than Water,” even scoring a supporting role in the latter. Although he eventually hooked up with Death Row and recorded a Dr. Dre diss on the “Too Gangsta for Radio” compilation, most of his subsequent output came through his affiliation with Mack 10, who released his second and final LP “Platinum Game” through his Hoo-Bangin’ Records in 1999. While he appears just a footnote in the West Coast rap saga looking back, “True Game” shows a complete artist with inspired lyricism and a musical vision who failed to parlay his significant talent into a long career.