“It’s like a jungle, sometimes it makes me wonder / how I keep from going under” is one of the essential lyrics that have accompanied rap for much of its existence. After Melle Mel and Duke Bootee first made the statement on “The Message,” it was sampled and cited many times. But what makes it so universal? As a summary of “The Message,” it heralds rap music’s role as a mouthpiece for urban despair and hope. “It’s like a jungle” is both a finding and a warning. It cautions us to be alert when we enter the impenetrable, dangerous perimeter that compares to a jungle. “Sometimes it makes me wonder / how I keep from going under” is doubt and triumph at the same time – the triumph (the keeping from going under) always imperiled by the impending downfall.

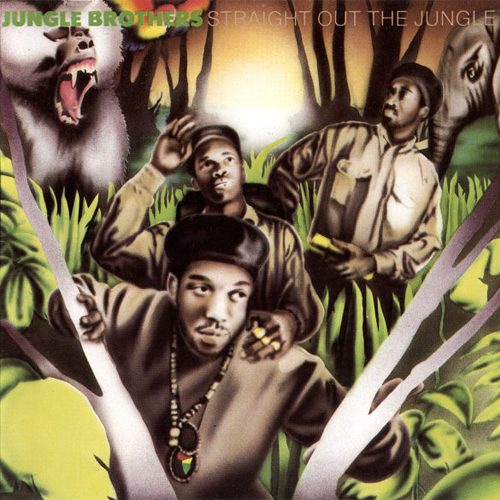

Since then legions of rappers have gone to lengths to explain how they keep from going under, with the most dramatic accounts often getting the most attention. Few, however, went about it as cool, playful and informed as the Jungle Brothers in 1988. True to their name, the Jungle Brothers presented themselves as a product of their environment. They came to us live and direct, straight from the concrete jungle. And as such they were well versed in the ways of the jungle:

“Educated man, from the motherland

You see, they call me a star but that’s not what I am

I’m a Jungle Brother, a true blue brother

and I’ve been to many places you’ll never discover

Step to my side, suckers run and hide

Afrika’s in the house, they get petrified

You wanna know why? I’ll tell you why

Because they can’t stand the sight of the jungle eye

They never fight or fuss, they never curse or cuss

they just stand on the side and stare at us

They get out of line, I put ’em on a vine

and give ’em one big push for all mankind

Now ain’t nothin’ to it, I just go ‘head and do it

I lay down the jungle sound and run right through it

And when I’m on the mic, I never stutter or stumble

cause I’m a Jungle Brother, straight out the jungle”

Afrika Baby Bam’s opening verse establishes the Jungle Brothers as a species apt at overcoming the obstacles. His partner in rhyme Mike G seconds him with a similarly slick performance (“Cool and quiet, but quick to start up a riot (…) I kicked a rhyme to the girl and she became my pet / I lent the sucker some juice and now he’s still in debt”), before they close detailing the dangers of the jungle:

“Struggle to live (struggle to live), struggle to survive

Struggle (struggle) just to stay alive

Cause inside the jungle either you do or you die

You got to be aware, you got to have the jungle eye

Take it from a brother who knows, my friend

The animals and cannibals will do you in

Cut your throat (cut your throat), stab you in the back

The untamed animals just don’t know how to act

It’s unbelievable (unbelievable) uncivilized (‘civilized)

And now I’m startin’ to realize

Danger in the jungle (jungle), the jungle means danger (danger)

Tension intense, hearts filled with anger (anger)

Men killin’ men just because of one’s color

In this lifetime, I’ve seen nothin’ dumber

So I think, before I make a move

Make sure my rhyme goes along with the groove

And backing on a brother when it’s time to rumble

My name’s Mike G (Mike G) and I’m straight out the jungle”

Sampling the famous lines from “The Message” mentioned earlier, “Straight Out the Jungle” is in some way the cocky offspring of that historic song, but it’s also a track that stands completely on its own, and, while not as influential, just as significant of a new direction in rap. The Jungle Brothers were part of a new wave of rap acts who wore their agenda on their sleeves, whose artist names already said it all – Public Enemy, Niggas With Attitude, Poor Righteous Teachers, X Clan, Brand Nubian, Intelligent Hoodlum, Geto Boys, etc.

“Straight Out the Jungle” was not just the first Afrocentric rap LP, it was also one of the first albums of the conscious rap genre. “Black Is Black,” also marking Q-Tip’s debut, was a call for black unity, Tip leading the way with two succint, simple verses that reached back to the civil rights movement, only to show what was still wrong in the ’80s. While not as urgent as Run-D.M.C.’s “Proud to Be Black” and lacking the intellectual prowess of Chuck D’s raps, “Black Is Black” reflected the youthful approach of the collective that would soon be known as the Native Tongues. The Marvin Gaye-inspired “What’s Going On” is rhetorically more refined, the duo depicting the less glamorous side of a drug dealer’s lifestyle. Mike G also briefly touches on the white worldview taught in history class: “Seein’ little of black and too much of the other / (They tried to brainwash you) / Picture that, a Jungle Brother…”

What prevented the Jungle Brothers from eventually becoming zealots was their humor. The title track, for all its – also musical – agility and cleverness, for instance possessed a taunting, tongue-in-cheek quality, from Bam’s “Say what?” adlib answering the African chant sampled from a Manu Dibango record, to the funky, sparse guitar licks lifted from Mandrill’s “Mango Meat” setting the track’s prowling pace.

In fact, in their heyday, the Jungle Brothers were probably more famous for their exuberant jams than for “Straight Out the Jungle,” “What’s Going On” or “Black Is Black.” It all began with “Braggin & Boastin,” the demo recording Mike’s uncle, DJ Red Alert, played on his KISS FM show. Mike G and Baby Bam (then calling himself Shazam) trade old school lines over a combo of “God Made Me Funky” drums and “Impeach the President” guitars. Built on a booming Sly Stone loop, “Because I Got it Like That” is an infectious, chest-thumping club track, whose appeal remains timeless thanks to the opening sing-song and the closing shout-outs to other cities. “I’m Gonna Do You” couldn’t be more clear about its intentions with come-ons like “You say you have a boyfriend, but like you said he is a boy / I am the real thing, and he is just a toy / somethin’ that you pick up, play with and put down / but girl, you can have me all year round.” “Behind the Bush” is the ensuing slow jam, steering clear of cheesy rap ballad territory and instead keeping with the image:

“I want to take you back to the motherland

and listen to the sounds of a steel-drum band

Climb up a tree, just you and me

cause that’s the way that I want it to be

Feel the breeze, put your mind at ease

See the pretty birds and the chimpanzees

After that, we’d step down to my hut

and together we’d split up a coconut

Watch the sun set, watch the moon rise

and then I’d proceed to make your nature rise

Behind the bush, baby”

Perhaps the crew’s most notorious song, “Jimbrowski,” was also one of the decade’s most bugged out rap tracks. They push the volume way past 10 on an accelerated Funkadelic break and turn the recording booth into a junior high locker room, providing their private part with a nickname that would stick, especially after it inspired BDP’s safe sex joint “Jimmy.” The Jungle Brothers’ claim to international fame was however a track that was not even on the original pressing of “Straight Out the Jungle.” The acid house classic “Can You Party” by Royal House, a Todd Terry production, happened to be recorded in the same studio and released on the same label. The ‘B Boy Remix’ of “Can You Party” already sampled Run-D.M.C., Afrika Bambaataa, and Malcolm X, so it wasn’t far fetched for the J. Beez to jump on it and give birth to the seminal hip-house track “I’ll House You.” Disregarding the musical backing and lyrical references to house, with its chants, short rhymes and adlibs “I’ll House You” is not much different from the other party tracks on the album. And with the house elements, it stands as one of the early blueprints for the fusion of rap vocals and electronic dance music that now seems more popular than ever.

But there’s more to the Jungle Brothers legacy. Although sometimes bordering on clichéd, they tried to put their music and message into an African context, turning the tribe vibes even up a notch on the instrumental “Sounds of the Safari.” Their conversational rap style, while partially harkening back to the old school, also announced a new era of rapping after the shouting matches of the mid-’80s. Under the tutelage of influential radio personality Red Alert, they tipped their hats to the pioneers, particularly with Afrika Baby Bam’s name referencing Afrika Bambaataa. They were the first rap group to be seen wearing outdoor gear (Timberlands, safari suits). And while it may not contain actual jazz samples, “Straight Out the Jungle” is clearly the jazziest 1980s rap album. Composed by Baby Bam – with help from Idlers owner Anthony Dick, Oswald Elliott, Red Alert and Jungle Brother DJ Sammy B -, it showcases the very basics of sampling and programming. It is a raw, genuine exhibition of creativity – but never for its own sake, but rather to create strong and substantial hip-hop music.

Then there’s a simple but effective symbolism to the jungle theme, the ‘jungle’ as a name designating various ghettos across America, while the natural habitat ‘jungle’ often acts as a counterpart to modern civilization, tropical rainforests being highly vital territories that are essential to life on this planet. The Jungle Brothers heed the call of the wild but they are wise enough not to trivialize or idolize it. And although they feel the pressure of the merciless law of the jungle, a sense of brotherhood permeates “Straight Out the Jungle.” Finally, in regards to rap, the sentence “Take it from a brother who knows, my friend” sums up, in a more friendly fashion, what every street rapper has been trying to tell us since the dawn of gangsta rap. Still the J. Beez were never tempted to pose as common criminals, the hectic “On the Run” instead addressing the fast pace of life in the city and the responsibilities of adulthood.

To conclude, there’s no overestimating the importance of this album. As an innovative landmark in rap album history, it’s practically on the same level as “Critical Beatdown” and “Criminal Minded.” As a 1988 album, it’s part of the outstanding class of ’88 (“Critical Beatdown,” “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back,” “Long Live the Kane,” “Follow the Leader, “By All Means Necessary,” “Straight Outta Compton,” “Power,” “In Full Gear,” “The Great Adventures of Slick Rick”…)

To get an idea of what the Jungle Brothers were on, consider the unreleased track “In Time,” available on the excellent 2010 Traffic Entertainment reissue of “Straight Out the Jungle.” Likely the original track behind the famous “Promo” (originally an “On the Run” b-side) that got heads excited for the A Tribe Called Quest debut, “In Time” features Q-Tip as well, the trio looking foward to a brighter future. But it’s Mike G who in retrospect steals the show with his opening: “In time this rhyme will be more than just a fantasy / A black man will be the man to claim presidency.”

Take it from a brother who knows, my friend.