Hanif Collins’ chosen nom de plume of Luck-One is in some respects a direct contradiction of his life experience. There’s nothing “lucky” at all about being arrested on robbery charges as a teenager, tried as an adult, found guilty and forced to serve a mandatory minimum sentence under Oregon law. Instead of going to college or entering the workforce, Collins was going to prison for half a decade, where he wound up in solitary confinement for two years. The press release for Luck-One consciously chooses to bring up this fact and frame it in the context of “political activism” and “food strikes,” but we only have their version of events to go by. Frankly I would think mentioning he was tried as an adult and sent to prison as a teenager would in itself engender sympathy for Collins’ outrageously bad luck – going extra with it only makes one skeptical about whether or not Collins was a prison philosopher or a problematic prisoner.

Regardless of what the unascertainable facts are regarding his incarceration, there can be no doubt Collins won converts OUTSIDE of prison with his “Beautiful Music” CD. The usual who’s who of hip-hop music bloggers hailed Luck-One as an artist on the rise, and our own writer Matt Jost described Luck as “grounded in the same firm, fertile artistic soil as Blu, Kero One, various Justus League alumni, or Portland’s own LightHeaded crew.” That’s far from faint praise. Collins also had some good luck in partnering with Dekk to produce his debut, who both Jost and the press release for his last album agreed was “next level” behind the boards. With lyrics that expressed a positive energy and spirituality without falling into the sometimes corny cliches of other praiseful emcees, Luck-One carved a niche out of the Pacific Northwest hip-hop scene which had a good chance of launching him nationally & worldwide.

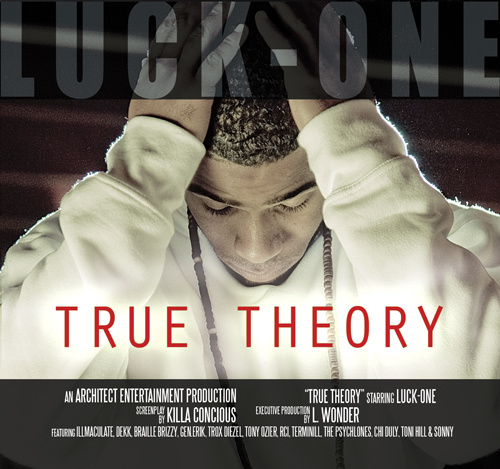

Luck-One has decided to spread the wealth out a little more on “True Theory.” No worries – Dekk’s talent for creating sonic backdrops hasn’t been kicked to the curb altogether. In fact his reverberating gunshot drums, big bass and subtle melodic backdrop can be heard on “The Real Me” just five tracks into what this CD calls Act One, and he also produces the “Warrior” joint for the middle third of this album labelled Act Two. Luck’s flow on the latter layered production is speedy and slick enough, but not enough to make Twista or Bizzy Bone jealous. That comes on the next song “Palestine,” one of those “rewind three times just to find out what he said” kind of tracks. What’s up with all these Acts though? One can judge from both listening to the album and looking at the artwork that Mr. Collins envisions this album as a movie or a play, with each third representing a different “Theory” of his life as he’s grown and evolved as a man. The first act is the more brash and ego driven portion of his journey. He offers “Resistance” to all forces opposing him:

“I used to point the gat and make these coward rappers sing

To be a soloist, static electricity don’t cling to me

At some point, I started nurturing the soul with good texts

History and scripture the books that I understood left

me yearning fervently, I seen possession just a trap

I let it GO! Became the voice of all my partners sellin crack

I see they blank stares (stares) feel like the way my fate twisted

I recreate theirs (theirs) it’s just the way they envisioned life

like it ain’t fair – spit out this flow needs circulation

So spare the Medicare and give us self-determination

[…] Philosophies the inner cities can stand on

Let’s give these devils what they planned on – resistance!”

The second act seems to be a rebirth for Luck, as he judges the context of his own life’s conflicts as pre-text to a jihad against negativity both internally and externally. By “Seraph” featuring Toni Hill he’s “looking at this whole globe, turning at a fast pace” and the religious theme is carried forward as both the song title and lyrical theme is angelic – i.e. “rising above” evil. “Me and Elohim got the same tat!” The next song “Monotheism” seems misplaced as a result, belonging in Act Two rather than Act Three, but that’s Luck’s choice. He brings in Braille and Gen. Erik to rock over the Terminill beat, and it’s a highly enjoyable posse collaboration.

In general Act Three is more somber than one or two, as Luck-One feels himself persecuted on all sides, fending off Lucifer’s persuasion in a world “where children are selling they labor” just to fend off hunger pangs while hard working fathers “tend to another man’s crops”on songs like “Hard For His Soul.” Luck-One’s storytelling on this track in particular is far superior to the sometimes ill-fitting Acts throughout the album, suggesting that the need to frame “True Theory” that was was unnecessary. Luck’s flow is mellifluous and soft spoken, tending toward the high octaves a DJ Quik fan would be familiar with, while lyrically trending toward the realm of Common or Nas in terms of his deeply considered verbiage. It’s all good on this relatively short 50 minute album, although Luck may be missing the marketable punchlines or imitable flow that leads to mainstream success. “True Theory” may add credence to the idea that he was a prison scholar silenced for his activism though, in that there’s very little negativity to his rap other than when he accurately narrates the world surrounding him. Luck’s a hard rapper not to like but he may also prove to be a hard one to market.