I came of age when music was still purchased in physical form at brick and mortar stores, and my relationship with music is different because of it. I used to go to record stores and sift through the bins looking for an album I wanted or one I didn’t know I wanted. There was a thrill in finding a rare CD in the bargain bin, or finding a new record used, or coming across something I didn’t even know existed.

I used to buy maybe four albums a month – I couldn’t afford more. I’d go home, reading the liner notes on the bus, and listen to the albums back to front multiple times. I’d listen to an album for a week straight, catching every nuance and change. Some of my favorite albums were those that required multiple listens to truly appreciate and discover: “Fear of a Black Planet” by Public Enemy, “Sandanista!” by the Clash, “Paul’s Boutique” by the Beastie Boys. I knew every inch of every album. To this day I’m still discovering songs that were sampled and referenced on early Ice Cube and Public Enemy records.

Then high-speed internet became more widespread and we entered an age where you can find almost any album ever made simply by searching for its name and “download” (Madlib’s “Blunted in the Bombshelter” being one exception). I went from listening to four albums a month to four albums a week, and sometimes as many as ten. The trickle of information became a flood, something this gig as a reviewer only exacerbates.

I no longer listen to an album for a week straight. I’m lucky if I listen to it twice in a row before moving on to something else. Instead, albums go on steady rotation, and it might take weeks or months or years before they begin to click with me. I burned a copy of Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” two years ago and only now am giving it a real listen, and I just went back to Percee P’s “Perseverance” after forgetting about it for four years. I also never listen to the end of a song – I know how all 2,000 songs on my iPod start, but I don’t have the patience to get to the end of any of them.

In some ways I love the fact that I can hear so much music. In the past few years, I’ve been able to explore and delve deep into African music, reggae, jazz, and hip-hop. If I’m in the mood to experience any genre, I go to Pandora and set up a “Salsa” or “Dirty South” radio station and get my fix. There are few albums so obscure or so rare that they aren’t available somewhere online, either legally or illegally. Indie artists that have a decent computer can record, mix, and post their music online for a fraction of the time and cost that it used to take. Small labels can sell digital copies of their catalogue long after they’ve lost the resources to maintain physical copies.

We are losing some things with the death of the album and the death of the record store. One is the social element of buying records. I had friends and acquaintances that worked and still work at record stores: Asa at Record Finder on Noe (now a dry cleaner), Gabe and Galen at Streetlight on Market, David at Amoeba on Haight. I’d talk to them about music in the store and over beers when I ran into them at a bar. They’d turn me on to things, I’d turn them on to things, and it made the process of shopping a social experience sorely missing from clicking “Buy” on iTunes or Amazon.

Another thing we’ve lost in the transition away from the album is the context and the power of an artists complete, fleshed-out thought. I listen to music in snippets now, and it is rare that I take the time to experience the breadth of what an artist has to say at a particular moment in time. I listen to track two then track three then track five of a totally different album. Any intentionality in the arrangement of songs on an album is totally lost.

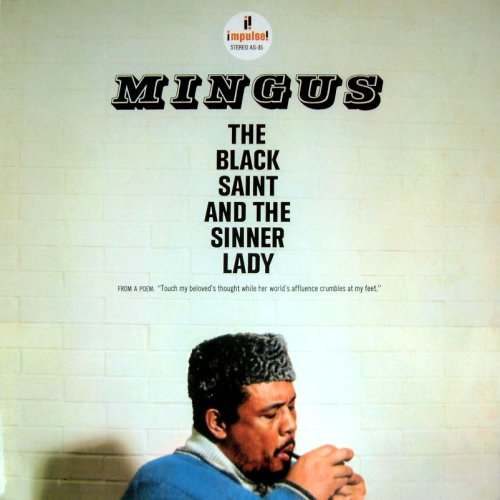

Which brings me to Charles Mingus’ 1963 masterpiece “The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady.” I bought album five years ago, new, for $15,98 at the soon to be defunct Border’s in downtown San Francisco. I had been told that it was a classic, a must-own record, so I decided to experience it first-hand. After an initial listen, I wasn’t impressed. First of all, it’s not an easy listen. It takes a while to build, and it is full of changes, contrasts, and discordant elements. It’s not nice background music. No one will play it at their wedding reception, but then maybe that’s the mark of good jazz. The album is four songs in about forty minutes, less music than I was used to paying so much money for. I later learned that the whole point of the Impulse label was to treat jazz as art and charge a premium for it. The records were expensive in the sixties and seventies when the label was active, and the reissues are expensive today.

Part of that money goes into the packaging, and for this reason you need to buy a physical copy vs. a download. It comes in a gatefold digipack like the original vinyl, with complete liner notes by Mingus himself and his psychologist. Mingus’s liner notes set the context for the album: what he was trying to do, how he went about doing it, the fact that it is essentially a song cycle about himself. The notes open up the music in the same way that the description of a painting in a museum catalogue can open up a painting, giving you a sense of the time and place it was created, and why it matters. You wouldn’t get the same experience from four lonely MP3s sitting in your iTunes playlist.

And the music? You need some time with that, too. This is an album that you can’t enjoy in small bursts. You can’t have this on shuffle. The songs all work together with themes and melodies and rhythms and ideas repeating themselves over the course of the disc. It’s a symphony, albeit a funky, groovy symphony. There are wailing horns, flourishes of brass, even some Spanish guitar interludes. It is celebratory, mournful, angry, happy, and as complicated and conflicted as the man who composed it. For experienced jazz fans, the album contains a multitude of nuggets, gems, and unexpected compositional choices that have ensured its place among the canon of essential jazz albums. For the casual jazz fan like myself, it is just challenging enough to be interesting while still being enjoyable. It pushes the boundaries of what I am used to, but isn’t so freaky or annoying or obtuse that I can’t listen to it.

For hip-hop fans who are interested in exploring the background and back story of their favorite music, “Black Saint” is worth purchasing. This, along with Coltrane’s “Love Supreme” and Miles Davis’ “Kind of Blue,” was the pinnacle of African-American music fifty years ago. The ambition, creativity, and talent that went into “Black Saint” can be seen in later hip-hop masterpieces like “Fear of A Black Planet,” “Speakerboxx/Love Below,” and “Liquid Swords.” “Black Saint” is an album that pushes both the artist’s and the listener’s comfort levels, aiming for greatness and largely succeeding.