It’s fall of 1984. I’m riding the school bus home from another day in the fourth grade. Two older boys pull out a smallish ghetto baster and start playing some music that is like nothing I have heard before. It starts with an ominous bell, and then a beat kicks in, joined by a synthesized funk track, all punctuated with cuts and scratches. The scratching acts like another instrument, chopping up the music and adding percussive elements. Then a man’s voice comes on, sing-talking in a style that I would learn was called “rapping.”

“Beat Street, the king of the beat

You see him rocking that beat from across the street

And Beat Street is a lesson too

because you can’t let the streets beat you”

That was my introduction to hip-hop and breakdancing, and I was hooked. I came to learn that it had originated in New York, and was supposedly a way for gangs to battle each other without violence. I had never been to any city, much less one as big as New York, but I immediately fell in love with this music.

My siblings and I embraced hip-hop culture. I got fat laces for my converse, and a hoodie emblazoned with “Breakin'” in graffiti writing. We set up cardboard in our living room to breakdance, which was facilitated by my family’s total lack of furniture. I wrote in bubble script all over my 4th grade binder. I learned how to windmill from the Hispanic kids at my school, who were were much more hip to what was going on. I was hooked.

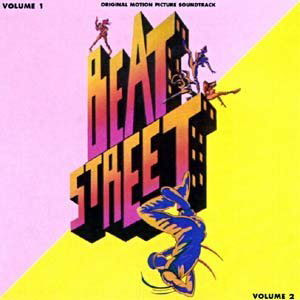

I was too young to see “Beat Street,” and had to settle for the lesser (but more kid-friendly) “Breakin’.” Still, I made my mom take me to the local drug store and popped down my seven or eight dollars apiece for each volume of the cassette version of the soundtrack. I remember bringing the tapes home, unpeeling the cellophane, and popping it into my Radio Shack tape recorder. I was so ready to enter the world of “Beat Street” and breakdancing. Instead, I got a crumby soundtrack with only two or three decent songs.

“Beat Street Breakdown” was and still is a powerful song. Sure, the music and rapping are dated and the unrestrained sincerity is corny by today’s standards. That doesn’t stop the song to be an epic poem about what hip-hop means to young people, how graffiti opened up a young kid’s world, all leading up to the tragic death of a graffiti writer. It reminds you of what hip-hop could have been had we gone the path of Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation, truly embracing the four elements.

Africa Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force are represented here with “Frantic Situation,” a kinetic blast of electro that went way over my 9-year-old head, although I can appreciate it today. The Phony Four MC’s had a novelty song with “Wappin (Bubblehead).” But as far as rapping, that’s about it. Most of “Beat Street” is made up of weak electro-tinged R&B like The System’s “Baptize the Beat,” Juicy’s “Beat Street Strut” and “Give Me All,” and ballads like Jenny Burton’s “It’s Alright” and Tina B.’s “Nothin’s Gonna Come Easy.”

Imagine how disappointed I was listening to this hoping to hear some fierce rapping, and hearing “Us Girls” instead. I felt like I had been brought right to the brink of this amazing culture, and then denied entrance. I didn’t know what other groups to listen to or how else to find out about the music. The local radio station would only play a few rap songs, and those were mostly rap interludes in R&B songs like Chaka Khan’s “I Feel For You.” I was hungry to hear hip-hop, and “Beat Street” didn’t come close to satisfying my hunger.

The one saving grace to “Beat Street” was the Treacherous Three’s “Santa’s Rap.” In the song, Kool Moe Dee plays Santa visiting the ghetto, while Special K and L.A. Sunshine heap abuse at him about how janky their toys were:

L.A. Sunshine: “You big fat whale you might as well quit

Cause I can name a hundred presents that I didn’t get

And if I did get a present it would be a hand-me-down

Yo I got this for Christmas now how that sound”

Special K: “It sounds good to me cause I’m about to freeze

you wanna see something look at the bottom of these

me and brothers can’t go out at the same time

cause a coat that’s theirs is a coat that’s mine”

Kool Moe Dee: “Man I know one thing y’all better get off my neck

And wait till you get ya welfare check

Go on down to the office and stand in the line

Better hurry up see I got mine

Jingle, Jangle, Jingle for the po

And once you get your welfare check

Yo kiss my mistletoe”

As I kid I loved the sing-songy rhymes about lyrics about Christmas in the ghetto. As an adult I realize how cutting that song was, especially considering it was essentially a novelty song. It remains one of my favorite hip-hop songs from that period.

By the time hip-hop and breakdancing hit my little beach town, it was pretty much over. Overexposure killed it. I moved on to new wave, convinced that hip-hop had been a fad. It was only several years later when my older brother got into West Coast gangster rap that I realized that there might be more to hip-hop than parachute pants and corny movies.

I’ve never gotten around to seeing “Beat Street.” I’ve read about it. How it was supposed to be true to the spirit of hip-hop. How it all got watered down in production. How they used real graffiti writers and then polished their pieces. Until this week, I hadn’t heard the soundtrack since the mid-80s. Listening to it now, it sounds as compromised and watered down as the film it is based on. Both volumes are out of print, volume two was never released on CD, and volume 3 was never released at all. I’d recommend seeking out “Santa’s Rap” and buying a compilation of Afrika Bambaataa and Grandmaster Flash’s greatest hits to hear the other good songs on this collection. The “Beat Street” soundtrack is obscure for a reason.