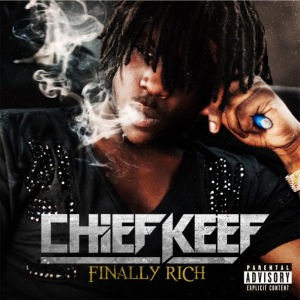

There were almost 500 homicides in Chicago in 2012, mostly shootings, mostly gang-related, and mostly involving young African-American men. The local street rap that eminates from Chicago’s most violent districts is called drill music. Drill is slang for revenge, and revenge factors heavily into many of Chicago’s homicides. Seventeen-year-old record label head, internet sensation, rapper, and father Keith “Chief Keef” Cozart is a product, chronicler, and possibly participant of the violence in Chicago. He grew up in Chicago’s South Side, one of the epicenters of that city’s recent wave of shootings, and is the most famous drill music artist. His debut album, “Finally Rich,” was released last month.

It’s hard to listen to Keef’s music without thinking about everything except the music. Here’s a guy glorifying gun violence who comes from a community wracked by gun violence, and who released his album days after the most horrific of 18 mass shootings in 2012. A guy who was implicated in the murder of a fellow rapper, who ran into parole issues after Pitchfork stupidly took him to a firing range for a video segment, thus violating his parole, and who has made a name for himself precisely because of his alleged “realness.” Like 50 Cent, who appears on the album, Keef comes custom wrapped in the authenticity of a criminal record. He also got a co-sign from Kanye West of all people, who remixed one of his songs and clearly influenced Keef’s rapping (more on that later). Fellow Chicagoan Rhymefest called Keef a bomb who was created to destroy, and Lupe Fiasco has also condenmend Keef’s music. There have been multiple articles in publications that don’t normally cover rap music on the implications of Chief Keef, what his art says about the state of the world, and the tricky racial politics of the few white critics, especially Pitchfork, who celebrate his music.

Amid all the press, PR, and controversy, its easy to forget that Chief Keef is an artist and an entertainer. If being a deplorable person disqualified people from being successful artists, some of the best music of the past fifty years would be off limits. Big L’s persona was a murderous sociopath, and Lamont Coleman was gunned down in the vein of the lifestyle he described on wax. “Lifestyles ov the Poor and Dangerous” is still a great album. Biggie was a woman-beating drug dealer, but “Ready to Die” is still one of the best rap albums ever made. Nas described having a shootout in a playground full of kids in “NY State of Mind” and that song is considered an all-time classic. Led Zepplin were occultists who abused groupies, Chuck Berry spied on women going to the bathroom, James Brown beat his wife, and even nice-guy Paul McCartney has his share of haters. With that in mind, I tried to listen to “Finally Rich” without all of the baggage of Keef’s backstory.

The problem is, without the backstory, there isn’t much about Keef’s music that stands out or warrants much attention. It’s pretty standard street rap: simple beats, simple rapping, and simple subject matter that never goes beyond cars, money, hoes, drugs, and the threat of violence. Women are exclusively referred to as bitches, men as niggas, and his haters end up “slumped over.” Ten mixtapes of this kind of hyper-DIY, hyper-regional rap get released every day by other sixteen-year-old aspiring rap moguls.

In some respects, Keef is just this year’s Waka Flocka Flame, another rapper with limited rapping skills and morally reprehensible subject matter. The difference is that at least Waka had energy and charisma. Keef comes off as a cold-hearted, dead-eyed teenager whose entire persona is based around acting like he doesn’t give a shit about anything and would love to prove it to you. What he does successfully is capture the sneering arrogance of a 17-year-old kid celebrating the good life. He’s taken inspiration from Kanye, but only in terms of Auto-Tuning his voice and assuming that being unlikable is a good look. (Which, judging from his internet buzz, hit singles, and $3 million record deal, it is). He mumbles and slurs his lines in a heavily affected drawl, always washed through layers of effects. As a lyricist, Keef is at times laughably bad. He’s borrowed heavily from Rick Ross’s rhyming dictionary, in which the best rhyme to any word is always that same word. In fact, Ross totally outshines Keef on “3Hunna” and Rozay is phoning his lines in. A prime example of Keef’s rudimentary rhyming is on his hit “Love Sosa,” where he raps:

“You boys ain’t making no noise

Ya’ll know I’m a grown boy

Your clique full of broke boys

God y’all some broke boys

God y’all some broke boys

We GBE dope boys

We got lots of dough boy”

On the title track he isn’t even trying to rap on beat. It’s almost as if the producer laid down the track on top of Keef’s rhymes and figured it was close enough. Keef approaches rapping with an almost zen-like purity. He strips it down to one or two themes and rhyme schemes and sticks to it for the entire track. “I’m Ballin’,” for example, is about how much money he has. The lyrics read almost like haiku:

“Sippin’ on that lean

I go hard for my team

Pockets filled with that green

I just blow it all on my team

Cause I’m ballin'”

Keef’s defenders, like the millions of people that watched his “I Don’t Like” video on YouTube, will say that by focusing on Keef’s limited lyrical ability I’m missing the point. Chief Keef isn’t a lyrical rapper. He is all about vibe and flow and putting on wax what it feels like to be a teenager from one of the roughest neighborhoods in America who finally got a taste of the good life. Like Waka, Keef’s music is about delivery and attitude, not lyrics. Complaining about his lack of rhyme skills is like complaining that punk bands of the 70s didn’t have any musical talent.

The problem with that argument is that Keef’s vibe is not something I want to spend time with. This might be a generational as much as stylistic issue. I’ve got two decades on Keef, and I’m probably the same age as the parents of many of his fans. Listening to Chief Keef reminds me of what a self-centered, self-righteous little prick I was at his age. It doesn’t reflect what I am going through now, it makes me cringe. He has none of the cleverness or charisma that make other asshole rappers’ music enjoyable.

Then there is the issue of context. There is something inherently sad about the fact that Keef has gotten huge by celebrating the traumatic, disfunctional world he comes from. Half his fans love his music because it reflects the world they know, and the other half love it because it shows them the edgy, “real” world that exists outside the safety of their parents’ suburban homes. I don’t know which is more depressing. Equally depressing is the fact that there is a high possibility that Keef will fall victim to the violence he came up in, and an almost certainty that he’ll end up in jail for parole violations. The best path forward for Chief Keef is that he’ll start using the same ghostwriter as Rozay and follow his career trajectory.

The production on the album is better than the rapping. The majority of the album is produced by Young Chop, with some help from K.E. On The Track, Y.G. On Da Beat, Mike Will Made It, and Casa Di. The beats mostly stick to the combination of skeletal snares and operatic synths of “Love Sosa” and “I Don’t Like.” It also veers in a more ambient direction on “Citgo” and “Kay Kay.” Both are from the Clams Casino school of ambient street rap. “No Tomorrow’s” trance beat points to the resurgence of ecstasy culture in rap music. Like Chief Keef, the beats walk the line between coolness and menace.

If the nihilism and casual disregard for humanity doesn’t turn you off on Chief Keef, then his sloppy approach to making music might. “Finally Rich” feels like a cynical cash-in, a hurriedly-released project that recycles the best moments of his mixtapes. “Love Sosa” and “Hate Bein’ Sober” are basically the same song with slightly different lyrics. 50 Cent comes by for a nice bit of swag vampirism, trying hard to stay relevant by attaching his name to a kid half his age, and sharing rhymes with Wiz Khalifa. Many of these tracks feel like they are first takes featuring lyrics that Keef came up with on the spot. This lends a certain spontaneity to the album, but also makes it feel rushed and half-baked. It’s hard to understand why you should be shelling out actual money for this album versus his free mixtapes, which were essentially the same thing.

In the end, “Finally Rich” is exactly what Keef’s fans want it to be. The music is perfect for bumping in their car, he has the attitude and money that they wish they had, and it will freak their parents and old white people out. Even a old hater like myself has to admit that “Love Sosa” and “I Don’t Like” are dumb fun. Most poeple probably have those two tracks, and there isn’t anything else on here that warrants buying this or taking the time to find a torrent of it. In the end, “Finally Rich” may not be the sign of the decline of Western civilization that its detractors make it out to be, but it is a soul-crushing listen.