I have a long and conflicted relationship with the Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy. I first encountered them in 1992 when they opened for Public Enemy at the Warfield in San Francisco. I had come to hip hop through punk rock, and was looking for rap as urban protest music. Public Enemy were my ideal as to what rap should be: righteously angry and calling out the injustices of the system. The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy seemed to embody these ideals.

They also put on one hell of a stage show. Rapper Michael Franti was basketball-player tall, and had a commanding voice and presence. His co-conspirator Rono Tse played industrial instruments, grinding electric saws against metal to produce a shower of sparks. When Rono wasn’t making his own version of a light show, he was dancing like a fiend. Opening for PE at their prime was no easy task, and the Disposable Heroes held their own.

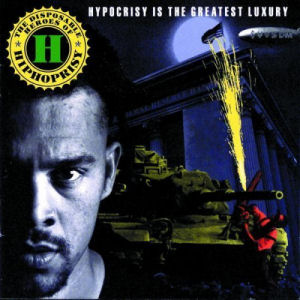

I immediately went and picked up their debut album, “Hiphoprisy Is the Greatest Luxury.” This is in the days when CDs came in album-length packaging so that they would fit in LP bins, and I cut out the front of the cardboard packaging and put it in the cover of my binder, so that the image of Michael Franti’s face with Rono taking a chainsaw to a tank in the background would stare at me while I was sitting in civics class. The Disposable Heroes seemed like the epitome of what I wanted hip-hop to be: they had innovative beats that built upon industrial music and their lyrics criticized homophobia, mass consumption, TV, and the war in Iraq. But as I listened to them, and as I got older, something changed. What had begun as a beautiful friendship disintegrated until I was not only soured on the group, I was soured on conscious hip-hop as a whole. It took me almost ten years to give conscious hip-hop another shot, and I’ve never listened to another Michael Franti project to this day. I saw a copy of “Hypocrisy Is the Greatest Luxury” in the bargain bins at Amoeba a few weeks ago, and decided to revisit the album and re-examine my feelings for it.

Tse and Franti came from outside the hip hop community. Their first group, the Beatnigs, made industrial music and was on punk label Alternative Tentacles, run by Dead Kennedys singer Jello Biafra. The Beatnigs could be described as funky industrial, incorporating elements of African-American music and featuring Franti’s booming voice as he rapped about Malcom X, the plight of the poor, and the evils of TV on the original version of “Television.” They arrived in hip-hop with that background in punk, industrial music, and far left politics that Franti shared with Biafra. Tse and Franti translated this into hip hop on “Hypocrisy.”

Franti and Tse worked with Consolidated producer Mark Pistel to program the beats for “Hypocrisy.” Pistel’s production for Consolidated combined pop, industrial, and hip-hop. He ditched the pop influence for the Disposable Heroes, instead going for a Bomb Squad-meets-Ministry sound. The album has the chaotic pastiche of samples that Public Enemey’s Bomb Squad pioneered, but it goes for a more alternative sound.

“Hiphoprisy” opens with one of the strongest tracks, “Satanic Reverses.” It starts with Islamic chanting, and then goes into bouncing, 90s b-boy beat full of wailing brass instruments with just a taste of industrial noise. It could almost be a Public Enemy song. Franti goes off like a younger Chuck D on a tirade against oil companies and how conservatives are destroying the country. The chorus is eerily prescient: “Bail out the banks/Loan art to the churches/Satanic reverses.” On this song, the group manages to perfectly meld all of their influences, delivering a rap song with the fire of punk and a political message that is righteous, pissed off, and on point.

They immediately jump the shark on “Famous and Dandy (Like Amos N’ Andy).” The song has a decent beat that combines early 90s dance with the industrial elements, but Franti’s rapping is stilted and preachy. The song calls out African-Americans for selling out to the Man to make money. Franti has some valid points, but it is presented in as artless and humorless a manner possible for a mind-numbing six and a half minutes. It’s immediately followed by more of the same on “Television, the Drug of the Nation,” another six and a half minute lecture presented in Franti’s nagging monotone. The beat is excellent, with noisy elements built around a funky bassline, but the lyrics sound like your dad after reading Noam Chomsky: “Television/Drug of the nation/Breeding Ignorance and feeding radiation.”

Most of the songs on the album are overlong. All but two clock in at over four minutes, and there are five that are six minutes or longer. It was the trend for rap songs through the late eighties to have long running times, but the Disposable Heroes illustrate why it went out of practice. It hurts the momentum of the album, and at best is too much of a good thing.

Take, for example, “The Language of Violence.” It’s a courageous song that took on homophobia years before popular sentiment had turned in favor of gay rights. To my knowledge it is one of the first rap song to address homophobia, and remains one of the few. The downtempo beat adds to the somber mood of the song, which details a young kid who is bullied for being gay. Unfortunately, not even the pioneering subject matter can totally make up for the awkward phrasings and excessive lenght of the song. It’s 6:15, about two minutes longer than it needs to be. Franti isn’t content with just describing a kid getting beat up for being gay. He also has to tell us about how his accusers get raped in jail. He delivers some powerful, insightful lines such as

“Dehumanizing the victim makes things simpler

…Something more easy to hate

An inanimate entity

Completely disposable

Easy to obliterate”

However, he also has his awkward and preachy moments, like when he tries to tie the abuse the kids give to the abuse they get at home:

“It’s tough to be young

The young long to be tougher

When we pick on someone else

It might make us feel rougher

Abused by their fathers

But that was at home though

So to prove to each other

That they were not homos”

The sentiment of that line is great, but the way it is delivered kills it. He’s got more syllables than the beat needs, he’s rhyming “home though” with “homo,” and really makes it clear that he cares more about making a point than making good music.

“The Winter of the Long Hot Summer” is another long, downtempo song, this time dealing with the first war on Iraq. Over a slow, relentless beat, Franti describes the trumped up case for war, the ultimately fruitless attempts to protest it, and the role the U.S.’s thirst for oil played in the decision to invade Iraq. It’s one of the more powerful and successful tracks on the album, even at eight minutes long. Again, Franti was a pioneer, one of the few voices speaking out about the war.

From that heavy song, they go into their shortest and punchiest track, “Hypocrisy Is the Greatest Luxury.” It’s another solid track. The beat is jumping, and Franti’s political commentary feels less tortured and forced. The result is a track that is banging and thought provoking at the same time.

“Everyday Life Has Become a Health Risk” is another rant, this time about polution. “Socio-Genetic Experiment” takes an interesting subject, Franti’s experience growing up in a multi-racial family, and ruins with a plodding beat and plodding rhymes. “Music and Politics” is a terrible jazz song about how Franti’s politics get in the way of his relationships. I’ll admit that my 17-year-old self thought the song was profound, but twenty years later it sounds as silly and self-important as high school poetry. Charlie Hunter’s guitar playing is nice, however.

The album picks up at the end. “Financial Leprosy” is a screed against consumerism over a funky beat. “California Uber Alles” is the Disposable Heroes one great song. It is a remake of a song by the Dead Kennedys which accused then-Californian Governor Jerry Brown of being a hippie fascist. The Disposable Heroes version took on Pete Wilson, the Republican who governed California from 1991-1999. Wilson was like a second Reagan, a conservative politician who became the focus of a lot of anger on the Left. The Disposable Heroes rip apart the governor and his policies with intelligence, anger, and humor, all over a rocking hip-hop beat. They delivered a middle finger to Governor Wilson that a lot of Californian liberals were dying to hear. They then close the album with the terrible “Water Pistol Man,” which features Franti singing. Luckily it’s at the end so it is easy to skip – I think that in all the times I listened to this album, I only listened to “Water Pistol Man” three or four times.

In the end, the preachiness of the Disposable Heroes is what turned me off on them and on conscious rap in general. As with many Christian rappers, the Disposable Heroes were more concerned about the message than the music, and as a result their music suffered. Franti’s rapping is often clumsy and stilted, and you feel like you are being scolded when you listen to it. The album also embodies the humorless, self-righteous,judgemental, holier-than-thou attitude that turned me off on the Left in the early 90s. There seemed to be such a focus on proving that you were less racist, less sexist, less homophobic, and more environmentally concious than everyone else. It felt less about trying to actually respect other people and understand where they were coming from, and more about proving your orthodoxy. As with the Disposable Heroes music, the sentiments were good but the way they were being delivered were problematic.

I listened to “Hypocrisy” a handful of times in the early 90s until I finally admitted to myself that it didn’t hold up musically. I suspect that happened to a lot of people. On paper, the Disposable Heroes were amazing. In reality, they couldn’t hold up to the other rap records of the day. It came out the same year as “The Chronic.” People blame Dre and gangsta rap for killing positive hip-hop, but I disagree. I think positive hip-hop’s boring preachiness is what killed the movement. “Hypocrisy” may be a far better album intellectually than “The Chronic,” but you can’t deny that Dre’s album was more immediate, more powerful, and sounded better than what Franti and Tse were doing.

Listening to the album two decades later, those awkward rhymes stick out like sore thumbs. In the context of other rap being made at the time, however, a lot of what the Heroes were doing was on trend. Guru, C.L. Smooth, Showbiz and A.G., and even UGK had their share of corny and clunky rhymes, and songs that went on a little too long. Public Enemy could be preachy at times, and Chuck D’s stentorian flow is as dated as Franti’s. “Hipocrisy” was made at a turning point in hip-hop, when it was transitioning from the old school to the newer class that were taking more risks lyrically and rhythmically. “The Chronic” is the perfect illustration of this, with Dre’s old school flow juxtaposed with Snoop’s slippery rhymes.

For their part, the Heroes had a fair amount of success. They got a lot of critical acclaim, they toured with U2, Public Enemy, and Rage Against the Machine, and they recorded an album of instrumental music over William s. Burroughs’ spoken word. They broke up soon after, with Franti going on to form Spearhead, a group I respect but have never gotten into. He seems to have found his niche, doing the soulful hippie hip-hop thing and sticking to his politics and values. Good on him for that.

Me, I lost interest in concious rap once I heard the Wu-Tang in 1993. I never bothered listening to Common, Talib Kweli, or Blackstar. I was afraid it would be more message over music, and I took a pass. Revisiting “Hypocrisy Is the Greatest Luxury,” I understand why I had issues with the genre. I also appreciated just how innovative the group was. The beats are always interesting and often amazing. Franti is taking on issues that few rappers before or since have tackled. He helped get punk and alternative kids to give hip-hop a chance, and showed how the two genres could overlap. In many ways the Disposable Heroes help set the state for Rage Against the Machine’s combination of politics, rock,and rap, El-P’s noisy beats, and Lupe Fiasco’s lyrics. As laudable as many of the Disposable Heroes efforts are, the fact remains that too often “Hypocrisy Is the Greatest Luxury” sacrifices music for message, which makes it a flawed album.