Let’s start this with a history lesson: Jamaican deejays are the grandfathers of rappers. Jamaicans were chatting over instrumentals at sound systems before anyone in the U.S. thought of doing it. It was a Jamaican immigrant, DJ Kool Herc, who introduced the concept to kids in the South Bronx, only Herc would use breaks from popular funk and disco tracks rather than dubs. Those kids ran with the idea and took it much farther than early deejays Dennis Alcapone, King Stitt or U Roy had gone. The earliest deejays were mostly concentrated on getting the crowd hyped by rhyming over instrumental versions of hits. As the art form developed, the deejays added more content, but much of the emphasis was on delivery than on lyrical content. Even a roots deejay like Big Youth filled much of his songs with vocal tics, and sounded like he was ad-libbing rather than rapping verses.

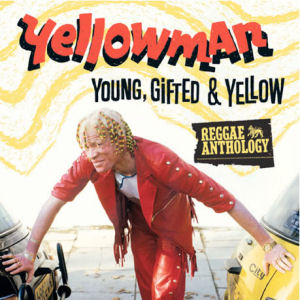

Winston Foster, better known as Yellowman, was one of the second generation of Jamaican deejays who, no doubt influenced by hip-hop, started including more content in his rhymes. It wasn’t just about making sounds or keeping a sound system jumping. It was about saying something. True, most of what Yellowman was saying in his early recordings was either crude or funny, but it was a definite evolution from the yelps, catch phrases, and stream-of-conciousness of the earlier deejays. He took General Echo’s style of funny, slack chants and ran with it, becoming one of the biggest dancehall artists of the 80s and releasing over fifty albums, even more if you count all the greatest hits and live albums. VP Records latest two disc and DVD box set gives a forty track overview of Yellowman’s work from the 1980s, including some of his biggest hits.

If you are like me, you know Yellowman through Eazy-E. The chorus of his 1984 song “Nobody Move Nobody Get Hurt” was sampled in Eazy’s “Nobody Move.” It’s no coincidence that Eazy sampled Yellowman. Both artists were unlikely sex symbols: Eazy was a short dude with a high voice, while Yellowman was an albino, who ranked very low in Jamaican society. In fact, a large part of Yellowman’s success was the fact that an albino had the gall to claim that girls were crazy for him, like on his first single “Mad Over Me.” Both Eazy and Yellowman combined raunchy lyrics with a healthy dose of humor. Eazy’s “Nobody Move” is about a bank robbery gone wrong, while Yellowman’s song is about Yellowman mouthing off to a police officer.

A lot of Yellowman’s material is based on slack humor. “Yellowman Is Getting Married” is followed by “I’m Getting Divorced,” describing how disillusioned Yellowman is with matrimony. “Morning Ride” is a not-so-subtle song about sex that no doubt ruined poor Fay Ellington’s reputation, whoever she was:

“Me ago tell you bout Fay Ellington

She work inna JBC station

She born Gemini month inna Portland

Say me take a 23 go a JBC

I didn’t sight Fay but I sight her man

He say I must come back quarter to one

I didn’t take a bus I take a minivan

The back of the van was Fay Ellington

She give me the morning ride”

It’s not all jokes, however. “Jah Mek Us Fi A Purpose” is a nice defense of his albino skin; “Herbman Smuggling” is a protest against the government crackdown on marijuana, “Eventide Fire” is a retelling of a 1980 fire at a home for the elderly that killed 153 people. There are also several romantic songs, including a remake of “The Girl Is Mine,” with Peter Metro singing Paul McCartney’s lines.

Then there is “Zungguzungguguzungguzeng.” It’s an amazing song, but who knows what it is about. The lyrics don’t really illuminate anything:

“Zungguzungguguzungguzeng

Seh if yuh have a paper, yuh must have a pen

And if yuh have a start, yuh must have a end

Seh five plus five, it equal to ten

And if yuh have goat, yuh put dem in a pen

And if yuh have a rooster, yuh must have a hen, now”

It doesn’t matter what he’s saying, because a lot of Yellowman’s charm is in his delivery. He has a singsongy voice that glides like silk over the riddims. Maybe it has to do with my limited understanding of Jamaican patois, but a lot of the appeal of dancehall to me is in its rhythmic, almost hypnotic quality. Not that the lyrics don’t matter at all, but they are secondary to the delivery, even for a more lyrical artist like Yellowman.

As good as this collection is, even I have to admit that it suffers from sameness. The cliche that all reggae sounds the same could definitely be made against “Young Gifted and Yellow.” Most of the riddims are mid-tempo dub tracks with little melody, and Yellowman chants at a mid-tempo with very little variation from song to song. Several riddims are repeated, and anyone who is familiar with 70s reggae will recognize the backing tracks, either from their original incarnations or the other versions of them. There are also a few songs that don’t quite measure up. “Galong Galong Galong” is a wicked track, but the misogynistic and homophobic lyrics make it hard to sit through, and the cover of “Blueberry Hill” is terrible from the Muzack instrumental to Yellowman’s crooning.

While the forty tracks of “Young, Gifted and Yellow” may be too much to take in at one sitting, in smaller doses it is an excellent overview of a talented and funny artist. Yellowman mixes clever wordplay, self-deprecating humor, and a skillful delivery, making it no wonder why he was one of dancehall’s biggest stars.